Three years ago I broke a promise to you.

In the spring of 2013, I wrote two articles on the digital technologies that were changing the way we do history: one on blogging (Digital History: A Primer Part 1) and one on digitizing documents and images (Digital History: A Primer Part 2). I promised to write a third article on what I called “Digital History For Real.” I never wrote that third one.

At the time I was scouring the internet for digital history projects that were using computer technology to produce new kinds of historical documents that I hoped would generate new historical questions or new historical methods, and eventually yield new ways of thinking historically and new insights into the past. To share what we were finding, we started The New Archive, a series of reviews of digital history projects. The first two entries covered an online archive about the Irish Easter Rebellion of 1916 and an interactive map called Visualizing Emancipation about the surprisingly long-term and often violent process of resisting and ending slavery in the U.S. Along the way, we found marvelous maps, archives of sounds, even a database of feelings. We found data visualizations of stunning creativity and graphic appeal. Our most recent front-page feature, by UT art historian John Clarke, displayed the ways gaming technology can be used to reconstruct ancient buildings and make them accessible to everyone. And about a year ago, in November 2014, we offered a list of resources on digital history, in case you wanted to start exploring on your own.

These projects were each presented in increasingly sophisticated and eye-appealing ways, which is important, but, for the most part, they were using digital technology to do the same kinds of history we have always done. I never wrote that third article because a new digital history hadn’t yet materialized.

Now I think that we are on the cusp of seeing some very impressive new uses of computational thinking and digital presentation of databases, mapping, and text mining – all of which have had more impact in digital humanities fields other than history until now. And I promise (!) that I will write something about those developments later this month.

First though, today I want to talk about the ways that historians have been using digital methods to make history more appealing and accessible to the public. This is the realm where Digital History and Public History overlap. So far, public history has benefited from the digital more than any other kind of work historians do.

I’m defining public history as any activity that makes high quality, professional historical research and writing available and accessible to the public. This differentiates it from popular history, which, at times, can be as good as public history but also includes all kinds of dubious junk.

Not Even Past is public history, like other kinds of online history writing and blogging. Public history, which appeared well before its digital enhancements, also includes the work of museums and archives, the preservation and display of historical sites, the collection of oral histories, and the production of documentary photography and filmmaking. Public historians work for private and public institutions, government and business. In 1979, the National Council on Public History was formed; its website is a great resource for information about doing and enjoying public history. And in 2013, The Digital Public Library of America was launched online as a national digital library.

The internet, computational technology, and digital film and photography have made much more professional history available to the public than ever before. Much of that newly available history is visually exciting and effectively interactive and it is changing the ways public and academic historians go about their work. In many cases Digital History and Public History overlap. The most obvious case is the vast number of online archives: digitized documents, books and other texts, films, photographs, and other images that are available to the public, while at the same time providing fundamental research materials for academic historians.

Another area of overlap is in the practices of openness and collaboration. Digital projects often require the work of people with diverse skills in programming, archiving, and data analysis, but collaboration goes beyond the specialists who produce projects. As Ben Schmidt put it, “collaboration in the digital humanities manifests itself not just among those involved in creating digital scholarship but also with the audience. Through comments and feedback sections, social networks, and other mediums, historians are able to engage with their audience on an unprecedented level.” This kind of openness to multiple voices is beginning to have an impact on academic history, but it has already been shaping many public history projects. For example, Vicki Mayer and Mike Griffiths describe their project MediaNOLA as a website for showing “the invisible contributions of ordinary people, places, and practices in the creation of New Orleans culture and its representations.” They quickly realized that in order to show the role of ordinary people in creating a city’s culture, they would need to engage those people in producing the website and that included training students to work with local librarians, archivists, and institutions.

Public interest in history is also served by collaborative, self-generated digital platforms. Television and movies, with all their romantic and entertainment oriented distortions, remain incredibly popular, but they are joined by outlets that satisfy the public’s desire to know “what really happened.” This is a question that can now often be answered easily and relatively authoritatively online. AskHistorians, for example, one of the many specialized and moderated pages of Reddit, the huge (sometimes scandalous and often misogynous) information sharing website, “aims to provide serious, academic-level answers to questions about history.” With 450,000 registered readers, AskHistorians is a lively open forum for discussing history. Crowdsourcing has its well-known problems, but it is worth noting that studies comparing Wikipedia and the venerable Encyclopedia Britannica carried out by Nature in 2005 and Oxford University in 2011 found them to be equivalently reliable.

Not only is there more historical information more widely available, but the technology has made all kinds of information available in exciting new visual forms that are relatively easy to produce. Data visualization is so popular now that there are dozens of free software programs that are openly available and easy to navigate and many other sites like Rice historian Caleb McDaniel’s, to instruct anyone on using them. We have already reported on excellent data visualization projects from big digital history labs like those at Stanford and Harvard as well as individual projects hosted at other universities and institutions elsewhere.

These visualizations raise important and unanswered questions about the differences between seeing and reading. To take just one example, a 14-minute video made in 2012 by Japanese artist Isao Hashimoto, illustrates each detonation of a nuclear weapon between 1945 and 1998, with a flash and a sound. One historian claimed that “almost anyone watching the animation will come away with a deep understanding of the key features of the nuclear age.” Now, while the video powerfully conveys the high number of explosions, it is impossible to derive a “deep understanding” of anything from watching it, because it violates almost every fundamental rule of historical presentation: it offers no way to think about or contextualize the data, and no way to verify its accuracy. Other commentators come closer to the mark in pointing out its emotional impact. For example, on Open Culture, Kate Rix called it “beautiful” and “eerie,” and said its laconic style makes it “work better” than excessive films like Oliver Stone’s historical psychodramas. Hashimoto’s video “works” as an art object because it generates feelings, conveys some generalized knowledge, and might stimulate the viewer to learn more. But it fails, in my opinion, to become anything more complex than a simple timeline, however beautifully rendered, because it lacks all analytical credibility and depth.

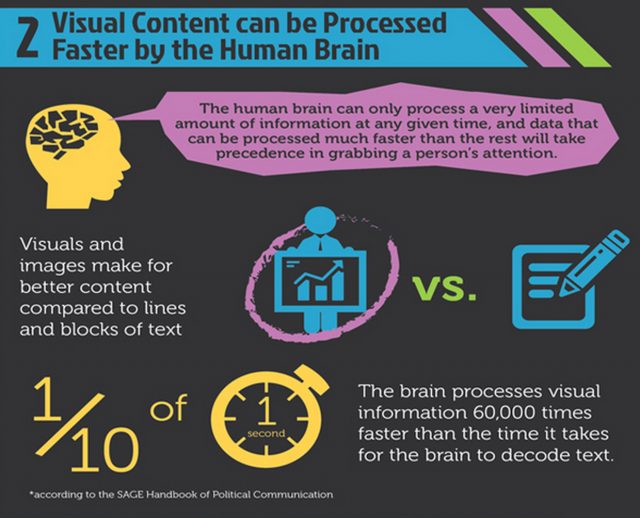

I’m not arguing against such visualization of historical data, just the opposite. We know that the visual has a visceral impact on us, an effect that often skirts around words and goes straight through our senses to our feelings. A famous (or internet-famous) marketing info-graphic claims (correctly) that we process visual information much more quickly than text. But what are we processing? What kind of history are we “learning”; can visuals that exclude the precision of words manipulate our feelings more stealthily?

I’m asking how we can harness that visceral and emotional power used by public and popular historians to academic data analysis. I’m also asking how we academic historians can do a better job writing for the public. One place to start is by asking how museums, historical sites, and films, for example, use that emotional power and our ability to identify with what we see to convey historical information and encourage thoughtful responses in their public audiences? How can we, as academic historians, work with professional public historians to learn what works in a documentary film or museum exhibit or Reddit, to understand how better to convey our own work to public audiences? And how can we apply this galaxy of ideas to our research and teaching?

This year at Not Even Past, we plan to dig much deeper into the ways that digitization and public accessibility are changing historical research, teaching history, disseminating history online, and training graduate students to become historians. I know I speak for many of my colleagues and readers, when I say that we are learning as much from our students about digital tools as we are teaching them.

We will also introduce a new page, Thinking in Public, devoted to public scholarship in all fields. One of the problems we face in entering these new fields is the lack of adequate archiving and indexing projects in digital and public history. Thinking in Public will seek to create a database of public scholarship projects conducted at UT Austin as well as to review and promote them. We will also be seeking to review the most interesting public scholarship taking place at other universities.

We have a new staff member to coordinate our Public and Digital History initiatives. He is Edward Shore, a UT History graduate student specializing in Brazilian history. You’ll recognize him as the author of some of our favorite NEP articles on Stan Getz and Joao Gilberto’s famous album and Hugo Chavez. Eddie will work with our current Senior Assistant Editor, Mark Sheaves, to commission and contribute to a series of articles about becoming historians in the digital age, and about their own forays into public history.

We will continue to offer the best historical writing in our reviews and articles, but we will also be thinking about how we can use new digital and public history practices to make us all better and more interesting historians who can speak to larger and more diverse audiences.

Featured image adapted from Steven Lubar, “Teaching Digital Public History,” January 2, 2014.