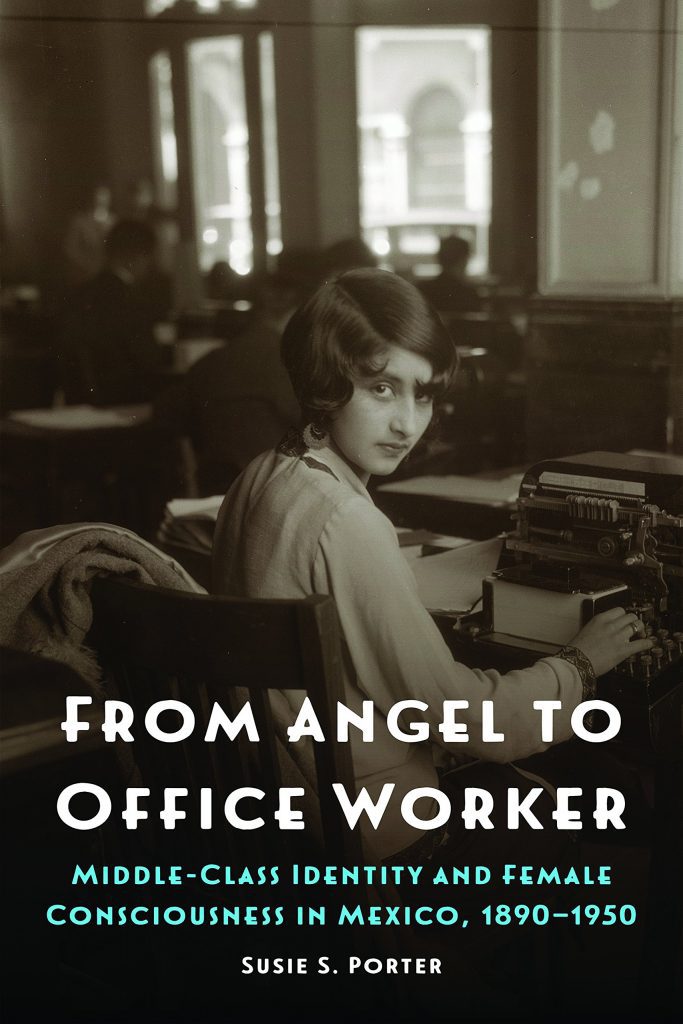

In this fabulous book, historian Susie S. Porter examines the material conditions of working women between 1890 and 1950 and the consequent formation of middle-class female identity in Mexico City. To highlight the historical existence of this social class in Mexican society, the author focuses her attention on the ways that societal practices and debates helped construct it. Porter’s class-based analysis of the early twentieth century Mexican women’s movement considers and engages both with public debate over the role of women in society as well as with women’s rights activism. Furthermore, she frames her research as part of a broader transnational history of women and gender that accounts for the contextually differentiated development of the “feminization of bureaucracy”. Taking into consideration the global feminist movements, the author represents how women’s work and feminist movements played out at the turn of the century, how they engaged and negotiated their position during and after the Revolution, and how they organized to demand improvements in their working and living conditions.

From Angel to Office Worker is a history of labor feminism. Porter’s primary contribution to this scholarship lies in her focus on the middle and working classes as a combined unit of analysis rather than as separate entities fighting different battles within the struggle for women’s rights. In doing so, she makes a case for the inclusion of the middle classes into labor studies as a whole. Porter’s study highlights the role of women’s schools and women’s later incorporation in the post-revolutionary bureaucratic system in office jobs, such as typists, archivists, and administrative secretaries. She later contends that their employment informed their activism. In constructing her argument in this way, Porter draws from a long line of feminist literature that asserts the importance of the written word (cultura escrita) in the political empowerment of women.

This, of course, links her research with female activism for the right to education, a history she traces in the implementation of schools for girls in the city, with a particular focus on the Miguel Lerdo de Tejada Commercial School for Young Ladies, inaugurated in 1903 under the governance of Porfirio Díaz. The importance Porter gives to commercial schools is an essential aspect of the book. She presents them as places of socialization where girls gained social and cultural through which they were able to find jobs and form networks of employed and educated women. These would become the nexus of feminist organized struggles.

One of the book’s most important contributions is the history Porter presents of the concept of feminism. As any sociopolitical concept, feminism has a conceptual history of its own that reflects how the concept has been used and defined depending on the historical, cultural, and social contexts it has been applied in. Thought the book, the author traces this conceptual history and in doing so explains the importance this has in the production of women’s history in Mexico. Hence, the book has a second function aside from studying the development of Mexican middle-class identity, namely tracing this concept’s incursion into Mexican society through its use and application to certain female-related practices. Susie Porter traces these practices through a meticulous analysis of the press. Her primary sources are mostly newspapers, both feminine and national ones. Media (film) is only consulted in the last chapter due to the study’s temporal focus. There is a book there waiting to be written.

The book is divided in seven chronological chapters, each of which that trace the Mexican history of the concept of feminism and of middle-class identity formation in parallel. Although From Angel to Office Worker concludes before women won the right to vote in 1955, the last two chapters engage with the early stages of suffrage activism. The book begins by tracing the discursive and material conditions of class in Mexico at the turn of the century. Thus, the first chapter conceptualizes the author’s class-based analysis and contribution. From there, Porter engages with women’s education and their incursion into the workplace (Chapter 2-3). Changes in women’s employment led to a shift from teaching, the feminine profession per excellence, to working in the bureaucratic system (Chapter 4-6). In these three chapters, the author studies and analyzes the female organizations led by women, which pressured the government to take into consideration and to apply reforms for women in order to benefit for the revolutionary government. The author’s historical analysis is impressive since the history of Mexican feminisms is a highly understudied topic. Finally, the book finishes off with an analysis of Sarah Batiza Berkowitxz’s book Nosotras las taquígrafas, and its filmographic adaptation by Emilio Gómez Muriel which the author argues exemplify the general concerns and perceptions of female workforces at a pivotal moment when a backlash aimed at removing women from the bureaucratic workforce struck.

Today, organized feminist struggles are at the core of political mobilization in favor of social justice in Mexico. One need only skim the news to see the pressure both government and society are under to dramatically modify the power structures that have historically oppressed women and feminized bodies. From Angel to Office Worker demonstrates that organized feminisms and the struggles for women’s inclusion in the workplace and society in Mexico is a century-old battle that has gone through many different stages, of which the book analyzes only one. By taking up the book, the reader can be certain that they will deepen their knowledge on the fundamental role women have historically played in the consolidation and creation of history, citizenship, and society in Mexico. More importantly, the readers will be surprised to see Mexican revolutionary and postrevolutionary history in a completely different light, one which separates itself from its highly masculine characters, premises, and common places.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.