The life of the American Civil Rights Movement of the mid-twentieth century was chaotic and confusing, and the telling of its history reflects this confusion. Often, the story of the movement is reduced to overly simplified depictions of a few prominent leaders: the righteous and powerful Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the brave and defiant Rosa Parks, and the controversial activist Malcolm X.

So much is lost in such retellings. In reality, the movement was in motion for decades and involved hundreds, if not thousands, of people working on the ground to rally and empower Black people nationwide. These often faceless men and women shadowed by the handful of great leaders have their own stories of adversity, struggle, and oppression. Such a story is found in the life of Cleveland Sellers and the SNCC.

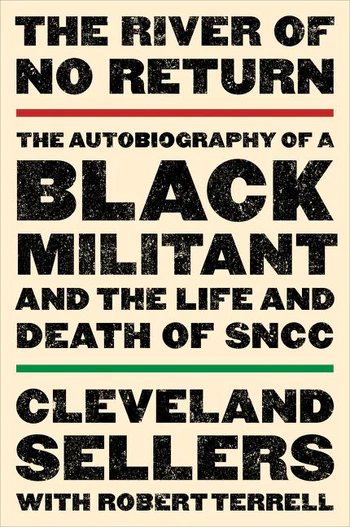

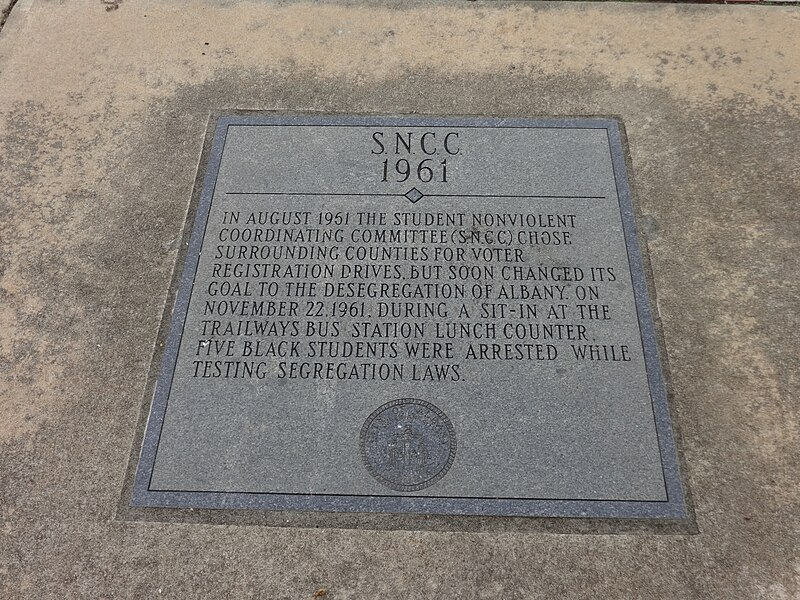

In his autobiography, The River of No Return, Cleveland Sellers provides powerful insight into the inner workings of the Civil Rights Movement and one of its most prominent organizations, The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). He sheds light on the complicated and often incredibly violent process of fighting oppression in the mid-twentieth century United States. Exploring themes of generational differences, ideological shifts within the movement, and white terror tactics, Sellers unfolds an inspiring story of struggle, pain, and the fight for Black liberation.

This is not a congratulatory story celebrating the victories of the Voting Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965 or how the courts and legal system were able to save Black Americans from the oppression that seeped into every crevice of their lives. It does not provide solace that the movement was successful and there was no further work to be done. Rather, Sellers’ story depicts the dirty underbelly of the rural south, one that was aggressive and unforgiving to those attempting to change the status quo, and the ultimate disappointments of the legal action taken in the name of “equality” for African Americans.

A talented and engaging storyteller, Sellers takes the reader on a journey through his childhood and early adulthood. It begins in his hometown, Denmark, South Carolina, a town with a very small, tightly-knit population and incredibly strict racial divides. Sellers describes the implicit discriminatory rules of his upbringing; a type of segregation was not necessarily aggressive or violent, but maintained through power and wealth. The Black and white communities of Denmark lived almost completely separately, and though the Black community was prosperous on its own, Sellers notes that the “specter of white racism” would always linger “like last night’s bad dream.” This prepares a peaceful yet ominous image that contrasts with the brutal racism, violence, and direct and outspoken oppression Sellers soon encounters. Like many other young, Black activists at this time, he left for college seeking involvement in the movement, with heavily strained parental relations in his wake.

There are numerous instances where Sellers describes in heavy detail the experiences of violence and fear the members of SNCC went through. These descriptions convey the hardship of this fight in a sense that cannot be grasped through a lecture or textbook. After he declares the movement as his first priority (over school or social life), Sellers leans wholeheartedly into his dangerous work, noting an SNCC leader who claimed they were now on “the river of no return”. Sellers builds tension as he describes his first march in Cambridge, Maryland. As the marchers approached the line of national guardsmen, the latter intended to put a stop to their march by any means necessary. The glinting silver of the bayonets, and the “Ah-HUMP CLUMP, Ah-HUMP CLUMP” sound of boots running towards the marchers illustrates the fear these people felt at the moment, which only increased as a soldier approached with a converted flame thrower filled with a substance stronger than tear gas. Sellers conveys with vivid imagery the screaming, panic, and hysteria that followed the gas attack that left people “too sick to help themselves” in the face of oncoming gunfire. These critical stories of terror and pain do not fit easily within the narrative that “nonviolence is the only answer”, which ignores the aggression and brutality the movement was often met with.

After beginning his work with SNCC in rural Mississippi, Sellers encountered a level of racism and white violence that he had never experienced before, and many would never experience in their lifetime. In Sellers’ view, white southerners held a general attitude that involved the idea that “their” Black communities were good ones, and outside agitators were coming in to “stir them up.” This meant the status quo and racial power imbalance were upheld without question, and black organizers posed a threat to it. While the SNCC worked to develop a grassroots campaign for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party in one of the most dangerous areas of the state, three SNCC members disappeared and were presumed dead due to racial violence. Here, Sellers uses detailed imagery to truly place the reader in the swamp and woods of rural Mississippi alongside the search party as they hiked in silence and darkness to avoid being detected by hostile white farmers.

A strong ideological division emphasized early in the book between the older and newer generation of Black Americans,is pointedly illustrated by Sellers through later conflicts between SNCC and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the organization headed by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The young members of SNCC leaned more strongly toward direct action, and felt they were responsible for fighting racial oppression themselves. Sellers details a feeling of moral right and wrong among the organization’s members. For them, the struggle was simply something that had to be done.

Unlike the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Dr. King’s method of large demonstrations attracting media attention to pressure action through the courts, the SNCC focused on poor black communities and organized them to take power in areas with a large black population. Sellers emphasizes the importance of grassroots organization to SNCC and empowering African Americans in their own communities. At the largest point of conflict between the two organizations, Sellers describes the vulnerable state the Southern Christian Leadership Conference demonstrations would leave the community in while SNCC lived and worked with the people, intentionally building up their political power and confidence.

Years passed, and after the assassination of Dr. King, the already fragile and weakened organization of the SNCC fell into even further disrepair amidst political and ideological divisions, financial difficulties, and increased aggression from law enforcement attempting to dampen the remaining sparks of the movement. Yet, not all was lost. Sellers describes his strong attachment to Black Power and its rise in response to lack of legal action from the federal government to solve the real issues faced by the black community: economic disparity and de facto disenfranchisement. The emergence of Black Power as an ideology and a movement provided a renewed opportunity for the organization to grasp onto, encouraging Black communities to believe in their autonomy and their ability to have power over their own lives.

Though Sellers finishes with the death of the organization he had dedicated years of his life to, his story is one of remarkable resilience. The movement consumed his entire life during this period, and he eagerly dedicated his blood, sweat, and tears to the cause of black liberation. Even still, he notes in the last words of his autobiography that he is not unique in his experience. There were many people who felt as strongly and acted as bravely in the name of the cause; they collectively “became one with the struggle”. Sellers was accompanied by numerous friends and colleagues dedicated to the same purpose: releasing Black Americans from the heavy weight of systemic oppression. They committed their lives; all floating together, down the river of no return.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.