By Mark Sheaves

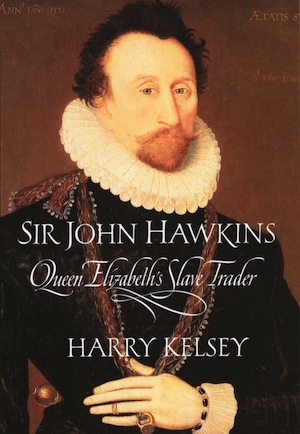

Following his successful biography of the famous English corsair, Francis Drake, Harry Kelsey turns to Drake’s lesser-known but equally adventurous cousin, John Hawkins (1532-1595). Born into a family of rugged traders and pirates in southwest England, Hawkins grew into a successful merchant and maritime navigator by his early twenties. This upbringing in a notoriously violent environment, Kelsey argues, created a fierce and pragmatic streak in the young trader. An ambitious individual, he turned his attention to Spain’s prosperous colonies establishing trading networks with merchants in the Canary Islands. Exposure to the emergent slave trade peaked Hawkins’ interest in this odious practice. In three separate voyages, he raided for slaves off West Africa and sold his cargo in the Spanish colonies of Santo Domingo and Venezuela. Despite Spanish legal restrictions against dealing with foreigners, Hawkins intimidated colonial officials into trade by harassing port cities until they agreed to terms. Financially successful, he developed good relations with Queen Elizabeth I. In 1578 he took up the position as Treasurer of the Royal Navy, playing a vital role in naval reform and coordinating the English victory against the Spanish Armada in 1588. From merchant to pirate to state officer, John Hawkins’ life comes alive for interested readers in Harry Kelsey’s lively prose.

Hawkins’ pirate exploits offered juicy source material for the English nationalist and imperialist propaganda that developed in the sixteenth century, but Kelsey offers a more nuanced interpretation of this “opportunistic individual.” Understood in relation to the shifting religious loyalties across Europe in this period, he argues that Hawkins developed a chameleon-like identity. He lived during the reign of four English monarchs who changed from Catholic to Protestant to Catholic and back again. Like many successful English men he pragmatically adopted the religion of each of these rulers. This ability also served him well when operating in the Spanish Atlantic. In 1568 he appealed to King Phillip II of Castile as a Catholic for the return of his possessions seized by Spanish officials during a failed deal in the Caribbean. To his credit Kelsey does not try to establish whether Hawkins truly identified as Catholic or Protestant. Instead he depicts an opportunistic individual driven by power, prestige, and wealth rather than religious or national loyalties.

Drawing on archives in Austria, Germany, UK, Spain, Mexico, and the US, Kelsey follows Hawkins through various locales scattered across the Atlantic world. This close attention to the individual means narrative rather than analysis drives the book. The author makes no attempts to situate Hawkins’ slave trading in the wider context of the slave trade and the Africans appear as faceless commodities. As a work of biography, however, the book represents a fascinating window onto the character and activities of Sir John Hawkins, English pioneer of the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Harry Kelsey, Sir John Hawkins: Queen Elizabeth’s Slave Trader (Yale University Press, 2003)

You may also like:

Ernesto Mercado Montero discusses Ordinary Lives in the Early Caribbean: Religion, Colonial Competition, and the Politics of Profit, by Kristen Block (2012)

Mark Sheaves reviews Francisco de Miranda: A Transatlantic Life in the Age of Revolution 1750-1816, by Karen Racine (2002)

Bradley Dixon, Facing North From Inca Country: Entanglement, Hybridity, and Rewriting Atlantic History

Ben Breen recommends Explorations in Connected History: from the Tagus to the Ganges (Oxford University Press, 2004), by Sanjay Subrahmanyam

Christopher Heaney reviews Poetics of Piracy: Emulating Spain in English Literature (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013) by Barbara Fuchs

Jorge Esguerra-Cañizares discusses his book Puritan Conquistadors: Iberianizing the Atlantic, 1550-170 (Stanford University Press, 2006) on Not Even Past.

Renata Keller discusses Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in the Americas, 1492-1830 (Yale University Press, 2007) by J.H. Elliott