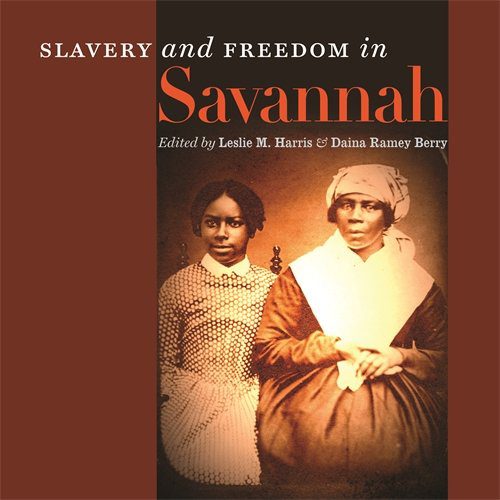

By Leslie M. Harris and Daina Ramey Berry

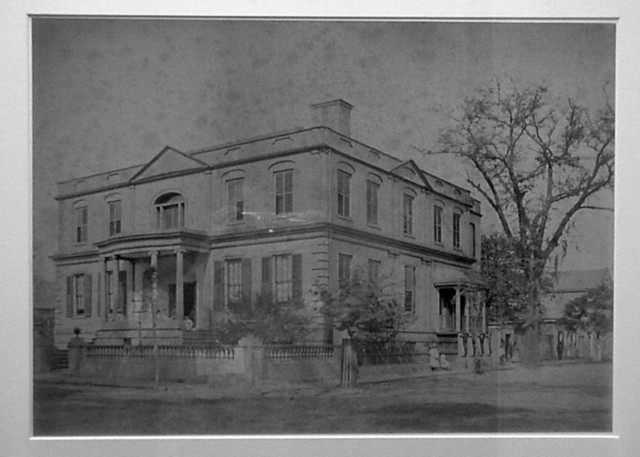

Slavery and Freedom in Savannah puts African Americans and slavery at the center of the history of a popular tourist destination. The Telfair Museum’s Owens-Thomas House is the most-visited house museum in Savannah. We worked with the museum staff to bring together the latest historical research on the role of African Americans in Savannah and the importance of slavery to the life of the city.

Telfair Museums plans to build on this research by incorporating the history of slavery more fully into its interpretation of the history of the Owens-Thomas house and the people who lived and worked there. This project builds upon some twenty-plus years of collaboration among museum professionals, academic historians, and historical archeologists, enabling major landmarks and historic sites in this nation to begin to tell more fully the history of non-whites and non-elites.

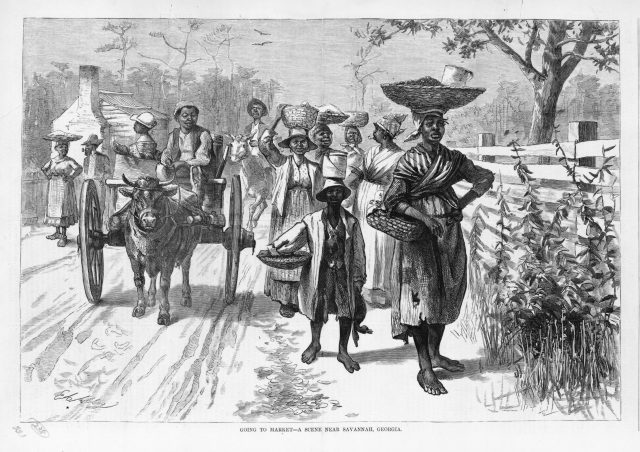

Savannah is a prime location for understanding the centrality of slavery and race to the national and world economy, and the importance of the city to southern landscapes and the southern economy. Because of the great economic and social dominance of rural plantation-based slavery in the Americas, historians have long assumed that that slave labor was not suited to cities and therefore slavery in American cities was insignificant. But a re-examination of slavery in cities throughout the Atlantic World has demonstrated the importance of urban areas to the slave economy and the adaptability of slave labor and slave ownership to metropolitan regions, especially port cities such as Savannah.. Urban slavery was part of, not exceptional to, the slave-based economies of North America and the Atlantic world.

Urban communities such as Savannah incorporated slave labor into their economic, social and political frameworks, often from the very beginning of their existence. By the time the Georgia colony was founded in the first third of the eighteenth century, it was difficult for the colonists or the trustees to imagine a world without slavery. Although the trustees, led by James Edward Oglethorpe, instituted a ban on slavery in the colony’s early years, in fact those same founders also requested and received black enslaved laborers from South Carolina to help them construct the city. Despite their own use of slave labor, Oglethorpe and his fellow trustees vigorously opposed proslavery colonists during the 1730s and 1740s. But many colonial residents believed that slave labor was necessary to the success of the colony, and to their pursuit of wealth, and found ways to work around the ban, importing slaves for various uses. By the time the ban was officially lifted in 1751, there were already 400 slaves in Georgia.

The slave population in Georgia grew rapidly after the ban on slavery was lifted in 1751. By the eve of the American Revolution, the colony held 16,000 slaves. Almost all of the forced migrants arrived in Georgia through the port of Savannah. Slave labor quickly became central to the economic success of the Georgia colony. Slaves were used to clear land, construct buildings, and cultivate rice and indigo.

The American Revolution and its aftermath was a time of great upheaval for the slave system in Georgia, and in the nation. For some, and particularly for enslaved blacks, it appeared that slavery might be on the verge of ending, even in the South. Despite the on-going struggle between slave-owning whites and blacks seeking freedom, the successful emergence of the slave-based cotton economy in the nineteenth-century in part guaranteed the continuation of slavery. Savannah grew to be the third-largest antebellum exporter of cotton in the South, behind New Orleans and Mobile. Rice and indigo were also important export crops that carried over from the eighteenth-century economy; rice reached its peak production in the region on the eve of the Civil War. Savannah flourished because of its location amid fertile coastal rice plantations, cotton plantations to the west, and Atlantic access to markets for raw materials, slaves, and finished products. The Savannah port also exported significant amounts of lumber and timber. The production of all of these goods involved the use of slave labor. Antebellum Savannah was one of the smaller southern cities by population, lagging far behind New Orleans, Baltimore and Charleston; only Norfolk, Virginia, was smaller in terms of major southern cities. But the enormous wealth produced by slaves is still evident in the gracious squares of the planned city.

On the eve of the Civil War, Savannah’s commitment to slavery was secure. But its economic success and political position in the south made its capture central to the Union army’s plan to crush the slaveholding republic. Although the city’s beautiful architecture was largely preserved, Sherman’s troops destroyed slavery and, temporarily at least, reordered the relationships between blacks and whites. Following the war, and in the face of strong and sometimes violent white opposition, blacks briefly gained access to the vote and political office, and expanded on antebellum institutions such as churches and schools. For the next forty years, blacks sought to negotiate their new roles as members of a wage-earning working class, hoping to carve a space in which to exercise their full rights as citizens. But by 1900, the gains blacks had made during Reconstruction had been replaced by legal segregation. Whites limited blacks’ access to the political realm, employment, and a host of other rights and privileges of citizenship. In response, Savannah’s blacks became active members of regional and national efforts to continue the march toward freedom and autonomy for African Americans, work that would not see fruition until the mid-1950s, when a series of Supreme Court decisions struck down legal segregation.

Featured image: Owens -Thomas House, Savannah, via Flickr by Denisbin

Here are Berry’s and Harris’s suggested further readings on urban slavery

You may also like:

Berry and Harris on 15 MInute History talking about urban slavery in the US south

Jacqueline Jones on Civil War Savannah

Henry Wiencek, Visualizing Emancipation(s): Mapping the End of Slavery in America

More articles on NEP about slavery