In November 2005, Anissa “The Assassin” Zamarron entered the ring for one of her most important bouts: a chance to win the Women’s International Boxing Association junior flyweight title. At 35, fighting in her opponent’s hometown and having lost her last four fights, Anissa was considered the underdog. San Antonio’s Maribel Zurita, a decade Zamarron’s junior, had earned the title three months earlier and was overwhelmingly favored to retain it. After ten full rounds, as the fighters awaited the scoring result from the judges, Anissa took comfort in the belief that she had fought the best match of her career. In the eight months since her last fight, she had eaten better and trained harder than ever before, and her preparation paid off: her trainer, Richard Lord agreed. “You did a great job,” he repeated, as the ring announcer came to the microphone. Anissa didn’t know it at the time, but it was her last fight, and she won: WIBA junior flyweight world champion!

Boxing Shadows tells the story of Anissa Zamarron’s life in Central Texas, including her rise to two-time world champion boxer. To those unfamiliar with the sport, Boxing Shadows offers a primer on the training, traveling, and match-ups of the early years of professional women’s boxing. Zamarron fought in the first sanctioned women’s bout in New York State along with a number of international bouts before women’s boxing was much of a blip on the radar of most American sports fans.

The Bennett sisters boxing, circa 1910.

But the book, co-written by Zamarron and sports writer Kip Stratton, is about much more. Boxing was not just a meal ticket for Zamarron, it was a life-saver. She was born in San Angelo, Texas, and her family moved to the Austin area when Anissa was seven. Shortly after, her parents separated and her family was divided. Her brothers — her heroes — lived with their father and Anissa went with their mother who, having married in her teens, relished a freedom she had never experienced before, to work full time, go to happy hour every night, and date. The loss of the structure of family life, the longing for the company of her brothers, and the rough and tumble apartment complex where she spent these formative years pushed Anissa further and further into darkness.

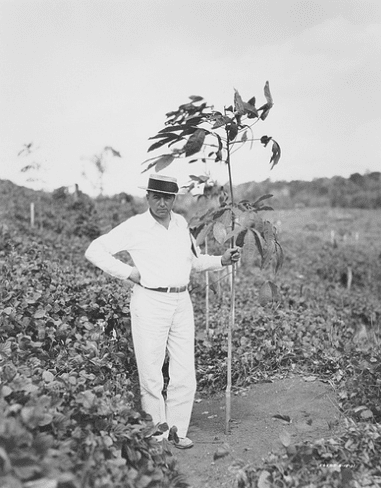

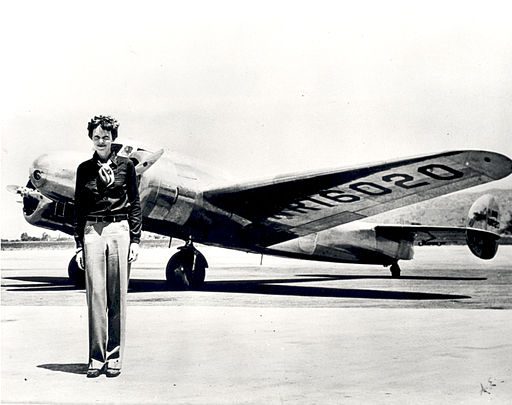

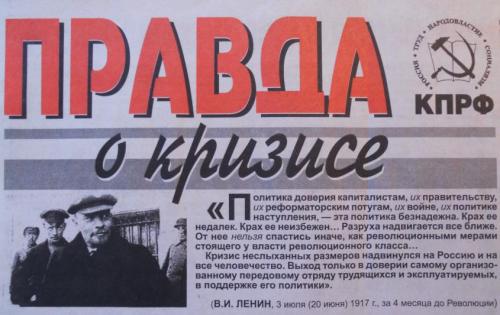

Anissa “The Assassin” Zamarron (The Women’s Boxing Archive Network)

Anissa felt a strong self-loathing as early as second grade, began cutting herself in middle school, and was committed to a mental hospital for the first time in her early teens. She discovered boxing in 1993 at age 23. After years of therapy, self-mutilation, and struggle, boxing was an outlet for the demons that drove Zamarron to hurt herself. Boxing did not end her battles with herself, but gave Anissa ways to work through challenges in the gym, rather than in her mind. Zamarron is open about her struggles with learning disabilities, mental illness, and drug addiction. Her success in the ring offers inspiration for others struggling to overcome similar challenges to reach their goals.

Master-at-Arms Seaman Rhonda McGee, left, spars with Patricia Cuevas during an exhibition match in the preliminary rounds of the 2011 Armed Forces Boxing Championship.

Boxing Shadows is devastating in its frankness, uplifting for its courage, and all the more impressive when one meets Anissa. In May of 2012, I visited Anissa at Richard Lord’s Boxing Gym in Austin, Texas to talk about Boxing Shadows. [You can see the video interview at the bottom of this page or on our Youtube channel here.] Zamarron is marked, more than scarred, by her past. She is surprisingly forgiving of those who disappointed her or otherwise contributed to the internal battles she fought as a child. After the interview, Anissa prepared to spar, and even then, nearly seven years after her last bout, in the ninety seconds it took Richard Lord to wrap her hands, the Anissa I had just interviewed was completely transformed. She forgot about the camera, disconnected from everybody in the gym, and began moving like a boxer — even standing still. Focused in a way I had not seen in the half dozen years I had known her, at that moment — “The Assassin” was back.

Video Credits:

Producer: Amanda E. Gray

Co-Producers: Therese T. Tran and Anne M. Martinez

Cinematographer: Therese T. Tran

Editor: Amanda E. Gray

Colorist/Online: Therese T. Tran

Transcriber: Lizeth Elizondo

Photo Credits:

All photos courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Except the photo of Zamarron in the ring, which comes from the Women’s Boxing Archive Network

You may also enjoy:

More by Anne Martínez, “Rethinking Borders”

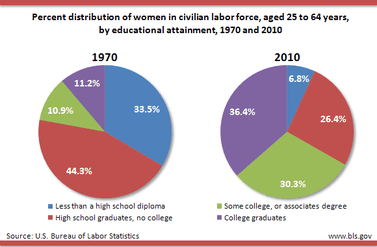

More on women’s athletics: “Title IX: Empowerment Through Education”

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.