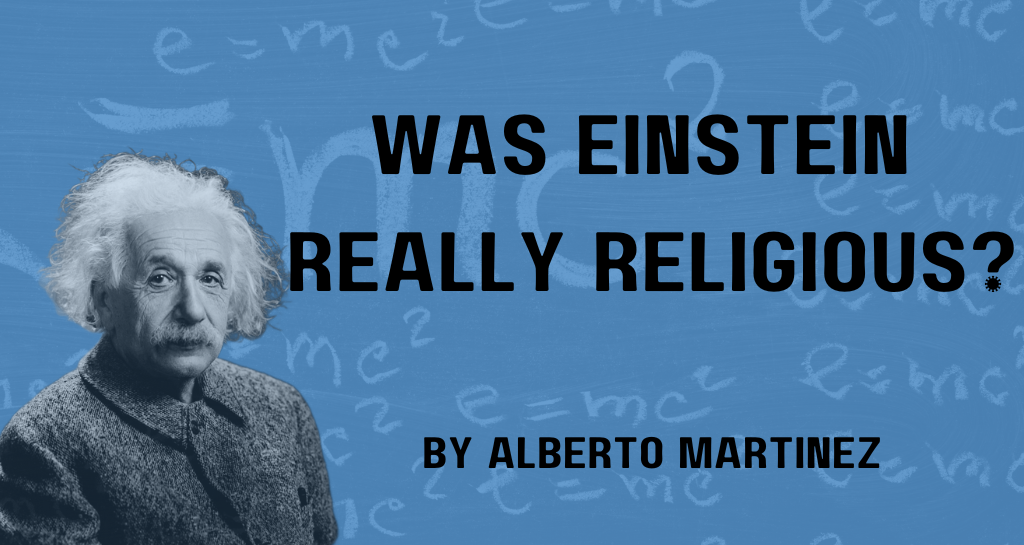

When he was a boy, yes. He lovingly studied the Bible, sensed no contradiction between Catholicism and Judaism, stopped eating pork, wrote little songs to God, and sang them as he walked home from school. But at the age of twelve, by reading science books, he abruptly abandoned all of his religious beliefs. He kept a “holy curiosity” for the mysteries and wonders of nature.

It is well-known that decades later, he made witty statements about God: that He does not play dice and that God is crafty but not malicious. Einstein famously wrote: “Science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind.” And the year he died, in 1955, a student quoted him as having once said “I want to know how God created this world. I’m not interested in this or that phenomenon, in the spectrum of this or that element. I want to know his thoughts, the rest are details.”

Yet Einstein’s statements on God were notoriously ambiguous. Therefore, many Jews, Christians, atheists, and others have embraced Einstein as one of their own—by picking his most appealing quotations. Atheists such as Richard Dawkins are glad that sometimes Einstein clarified that by “God” he actually meant to say “nature.” Yet sometimes he remarked “I am not an atheist.” Other times Einstein said that he believed in the God of Spinoza. In the 1670s, the Dutch philosopher expressed great reverence for the lawful harmony of nature, arguing that God has no personality, consciousness, emotions, or will. In 1929 Einstein praised Spinoza’s outlook as a “deep feeling in a superior mind that reveals itself in the world of experience.” Yet at the same time he expressed doubts as to whether he could fairly describe himself as a pantheist like Spinoza.

In his #1 New York Times bestselling biography of Einstein, Walter Isaacson argues that Einstein did not use the word God as just another name for nature. Isaacson insists that Einstein was not secretly an atheist but instead, that Einstein believed in an impersonal Creator who does not meddle in our daily lives. Likewise, many other writers also think that since Einstein did not believe in a personal God, a fatherly Creator who cares about us, and not being an atheist, that therefore he believed in an impersonal God.

In 1936, Einstein wrote a letter to a little girl, in which he explained: “Everyone seriously engaged in science becomes convinced that the laws of nature manifest a spirit which is vastly superior to man, and before which we, with our modest strength, must humbly bow.” This certainly sounds religious, but what did he mean by “a spirit”? Einstein’s replies to inquisitive strangers, children, reporters, or close friends sometimes were markedly different. In some cases, he used colloquial expressions that he preferred to rephrase in more exacting contexts. He voiced regrets that many of his casual expressions later became subject to public dissection.

In contrast to the famous quotations that portray the old Einstein as a religious man, it is less well known that he privately described himself as agnostic. In 1869, “Darwin’s bulldog,” Thomas Henry Huxley coined the word “Agnostic” as an attitude of temporary reasoned ignorance, to not pretend to know conclusions that have yet to be demonstrated scientifically. Twenty years later, Huxley commented: “I invented the word ‘Agnostic’ to denote people who, like myself, confess themselves to be hopelessly ignorant concerning a variety of maters, about which metaphysicians and theologians, both orthodox and heterodox, dogmatise with the utmost confidence…” Popularly, agnosticism became known simply as the position of admitting that one does not know whether God exists.

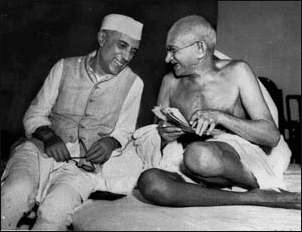

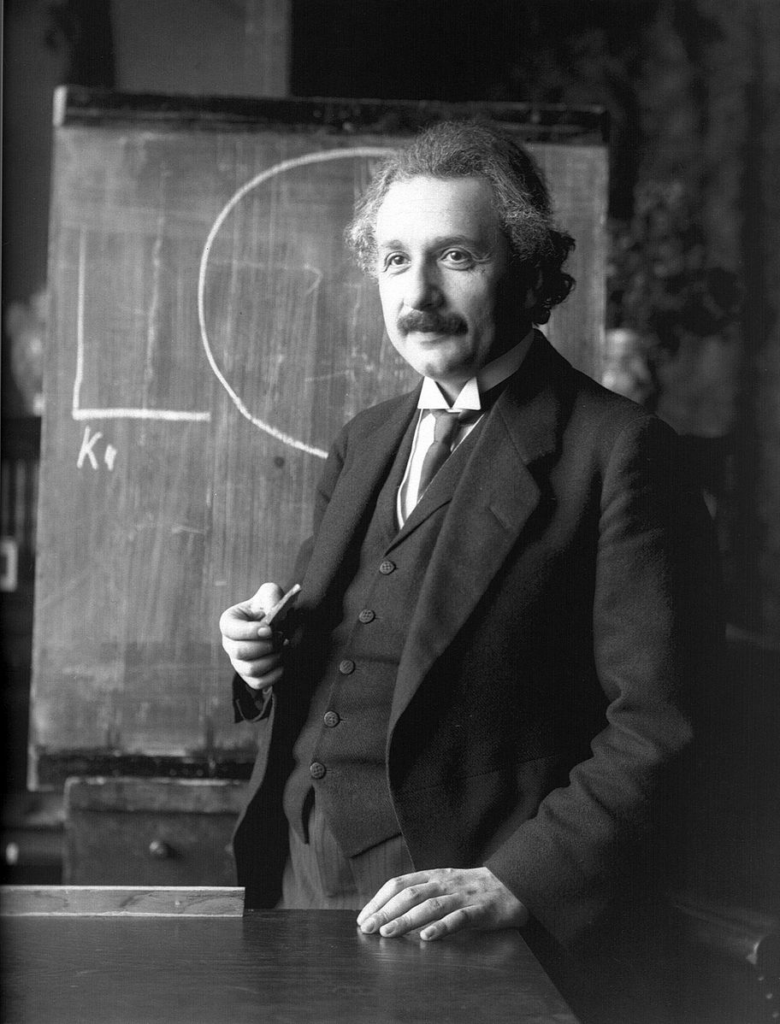

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In 1949 Einstein wrote a letter to a curious sailor in the US Navy, explaining that “You may call me agnostic.” In 1950 he replied to another correspondent: “My position concerning God is that of an agnostic. I am convinced that vivid consciousness of the primary importance of moral principles for the betterment and ennoblement of life does not need the idea of a law-giver, especially a law-giver who works on the basis of reward and punishment.” Then in 1952, in a letter to a philosopher, Einstein frankly expressed his unsweetened opinions: “The word God is for me nothing more than the expression and product of human weaknesses, the Bible a collection of honorable but still primitive legends aplenty. No interpretation, no matter how subtle, can change this (for me).” Einstein added that the Jewish people were no better that any other groups of people: “I can ascertain nothing Chosen about them.” He said that all religions are “primitive superstitions.”

He wrote such stark comments in private letters, in contradistinction to his published pronouncements about God and religion. So, was Einstein really religious? Or was he politically correct in public? In 1930, at the age of fifty-one, an article was published in which he described himself as “deeply religious.” But by then he was a world-wide celebrity. He knew that every word he said might be analyzed and interpreted. Over the years, he explained that he was religious only inasmuch as he felt a deep sense of wonder and reverence for the laws and mysteries of nature.

But what do we usually mean when we say that someone is religious? Most of the beliefs and practices that we distinctively associate with religious people were absent in Einstein. He denied the existence of a God that cares for humans, he argued that there is nothing divine about morality, he did not believe in any holy Scriptures, he had no faith in religious teachings, he rejected the authority of all churches and temples, he belonged to no congregation, he denied the existence of souls, life after death, divine rewards or punishments. He denied the existence of miracles that suspend the laws of nature. He rejected all mysticism, he did not believe in free will, he did not believe in any prophets or saviors. He denied that there is any goal in life or in the order of the universe, he practiced no religious rituals, and he did not pray.

Having rejected most aspects of religion, the young Einstein had some options: either say that he was not a religious person, or instead, find an alternative way to define religiosity. He chose the latter path. In science, Einstein had great success by redefining traditional concepts: he redefined concepts of time, energy, mass, gravity, and more. So he tried to do the same thing with religion. In 1950, he explained to his close friend from youth, Maurice Solovine: “I have found no better expression than ‘religious’ for confidence in the rational nature of reality as it is accessible to human reason.”

Instead of accepting Scriptures, rituals, or traditions, Einstein focused on the wonders of nature. By redefining religion to include at its core the emotions and attitudes that Einstein did cultivate, then and only then could Einstein describe himself as a deeply religious man. For example, he called himself deeply religious, but he did not pray. Therefore, in his new definitions, not praying became an act of a deeply religious man, one who fully trusts the laws of nature. He once wrote to Leo Szilard: “as long as you pray to God and ask him for some benefit, you are not a religious man.”

Summing up, good old Einstein was agnostic, I don’t think that he was very religious. Forgive me for making an unscientific analogy. Suppose someone tells us that he really loves pizza, but then he says that he prefers no sauce, dislikes dough, is allergic to cheese, and believes that anyone who asks for toppings does not really like pizza. Then we ask: but how can you say that you really love pizza? He answers: “because I have a deep appreciation for its essence.”

The Letter

In 2008, the letter from Einstein on the subject of religion stunned the public and was sold at auction for a staggering £207,000 ($404,000) instead of the £6000-8000 estimated by Bloomsbury Auctions.

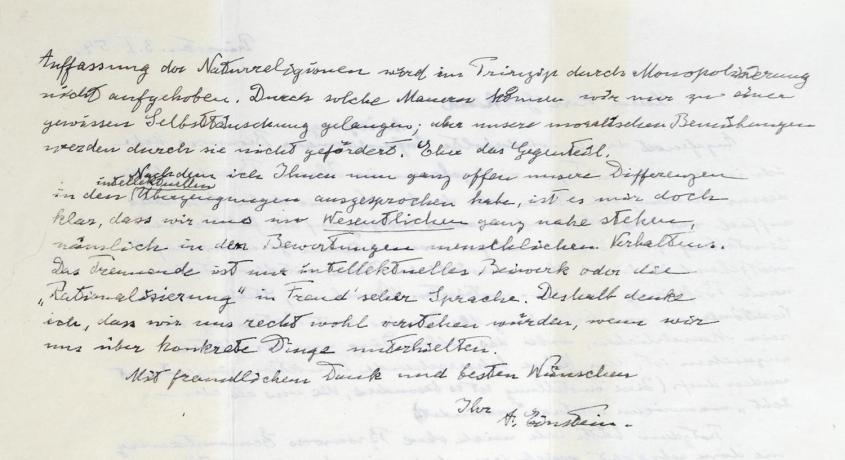

Source: Albert Einstein to philosopher Eric B. Gutkind, 3.1.1954, Einstein Archives, item 33-33.

Alberto Martínez translates part of the letter here:

The word God is for me nothing more than the expression and product of human weaknesses, the Bible a collection of honorable but still primitive legends aplenty. No interpretation, no matter how subtle, can change this (for me). Such refined interpretations are naturally highly varied and have almost nothing to do with the original text. For me the unmodified Jewish religion, like all other religions, is an incarnation of primitive superstitions. And the Jewish people to whom I gladly belong and with whose mindset I have a deep affinity, have no different quality for me than other people. As far as my experience goes, they are also no better at anything than other human groups, though at least a lack of power keeps them from the worst excesses. Thus I can ascertain nothing “Chosen” about them.

Overall, I find it painful that you claim a privileged position and seek to defend it with two walls of pride: an outer one as a man, and an inner one as a Jew. As a man you claim a certain exemption from otherwise valid causality; as a Jew, a privilege for monotheism. But a limited causality is no longer causality, as our wonderful Spinoza had first said in the strongest terms. And the animistic interpretations of natural religions are also through monopolization not invalid. With such walls we fall essentially into self-deception, but they do not help us in our search for a higher morality. On the contrary.

Now, though I have in all honesty expressed our different beliefs, I still have the certainty that we largely agree on important matters, e.g. in our assessment of human conduct. What separates us, in Freud’s terms, are intellectual “supports” and “rationalizations.” I therefore believe that we would understand each other well if we were to talk about concrete things.

With friendly thanks and best wishes,

your

A. Einstein.