NEP’S Archive Chronicles explores the role archives play in historical research, offering insight into the process of conducting archival work and research. Each installment will offer a unique perspective on the treasures and challenges researchers encounter in archives around the world. NEP’s Archive Chronicles is intended to be both a practical guide and a space for reflection, showcasing contributors’ experiences with archival research. This two-part installment explores the Archive of Indies in Spain and shares research tips on how to navigate its digital platform, PARES.

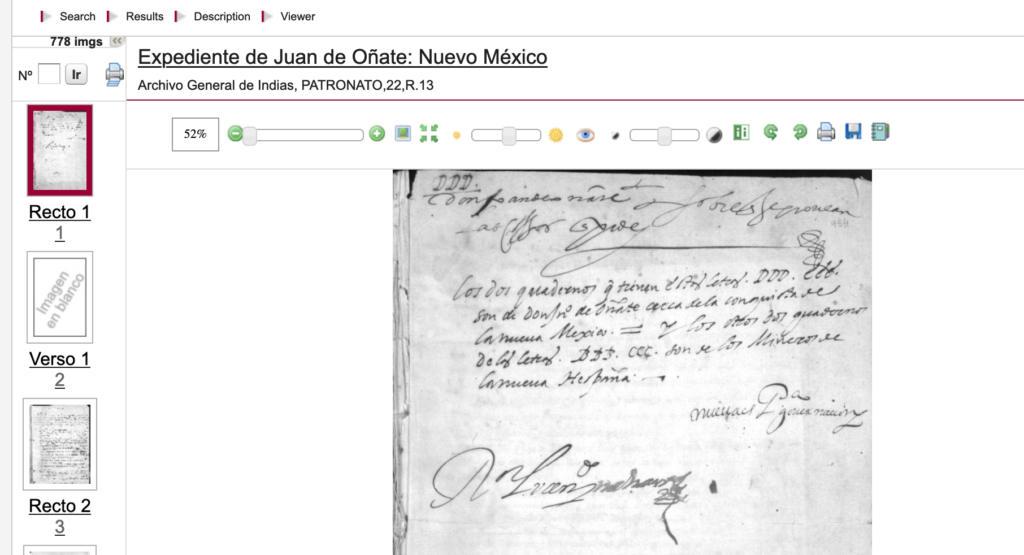

For nearly a decade, I experienced the largest imperial archive of the Americas from afar. In Mexico City, Guadalajara, and Austin I logged countless times onto a website called PARES (Portal de Archivos Estatales), a clunky but essential tool for those in need to peruse the Spanish State Archives. The most recent iteration of the PARES website allows you to create an account called a “Notepad” where you can save archival references and digitized documents. Below a selection of documents that I vowed to myself I would look in person one day:

- Dibujo de un bisonte

- Plano, elevación y perfil de una casa para habitación del Catedrático de Botánica

- Alojanieve, pulperías, salinas y solimán

- Consulta del Consejo de Indias

- Ensalada de los Navegantes: Disertación phisicobotánico-médica

I have yet to see these documents.

Even though PARES contains the online catalog and millions of digitized documents from twelve archives, most of the items I have collected over the years come from a single repository, the Archivo General de Indias, known to most scholars as the AGI. In 2013, I did not understand what kind of archive the AGI was, let alone grasp the magnitude of its holdings. All I knew is that I had to visit someday if I wanted to become a respected Historian (una historiadora consagrada). Why such a visit was necessary truly escaped me. Up to that point, I had learned that historians of science worked mostly with print material and archives of renowned scientists and scientific institutions. As I tried to piece together the dispersal and loss of the visual culture produced in the Royal Botanical Expedition to New Spain, I longed to visit the Royal Botanical Garden of Madrid and its archive. This kind of repository was closer to the natural history collections I had known as an undergraduate while I worked at Mexico’s National Herbarium. And yet, I continued filling my PARES notepad with items from the Archive of the Indies and collecting archival references from the secondary literature I consulted.

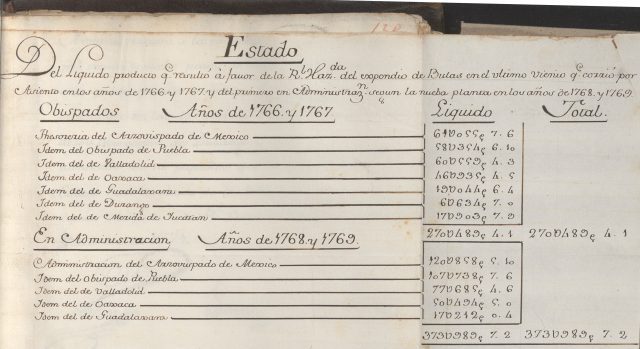

It would take me at least another five years to learn why this archive was relevant to those studying the history of science and knowledge in the early modern Iberian world and beyond. Important books and scholars (including my own advisor and fellow colleagues) helped me understand that the Spanish Empire was held together by a large bureaucratic apparatus that was capacious enough to collect information about almost anything and anywhere. From taxes and commercial disputes to the number of trees planted in Chapultepec, the bundles of documents or legajos at the Archive of the Indies are a true unknown to the researcher, each carrying in their pages a unique blend of calamity, confusion, hope, excitement, and occasional boredom. However, finding what you need is rarely a straightforward journey. The AGI’s vast holdings are spread across seventeen main archival sections, including a relatively new addition listed in PARES as ADAGI (Archive of the Archive of the Indies). How then, does one determine where your archival journey should begin at the AGI?

The easiest and most practical answer lies, of course, in PARES. In principle, it should simply be a matter of compiling the archival references saved in one’s notepad and then tallying the sections that appear most frequently. For this purpose, one could use the thorough guides made by Scott Cave or recent ones posted on H-Net by William Cohoon and Grant Kleiser. Indeed, this is the method I initially followed in preparation for my dissertation research on the commerce and cultivation of New World dyes in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. My numerous PARES searches indicated that the section of the archive that dwelled on dyes was Contratación (commercial affairs, very broadly understood). Based on these references, I realized my time at the AGI would largely involve examining commercial disputes over dye shipments. To be honest, I was not thrilled by this prospect and thus decided to prioritize a different archival thread that drew me to the history of cochineal some years earlier.

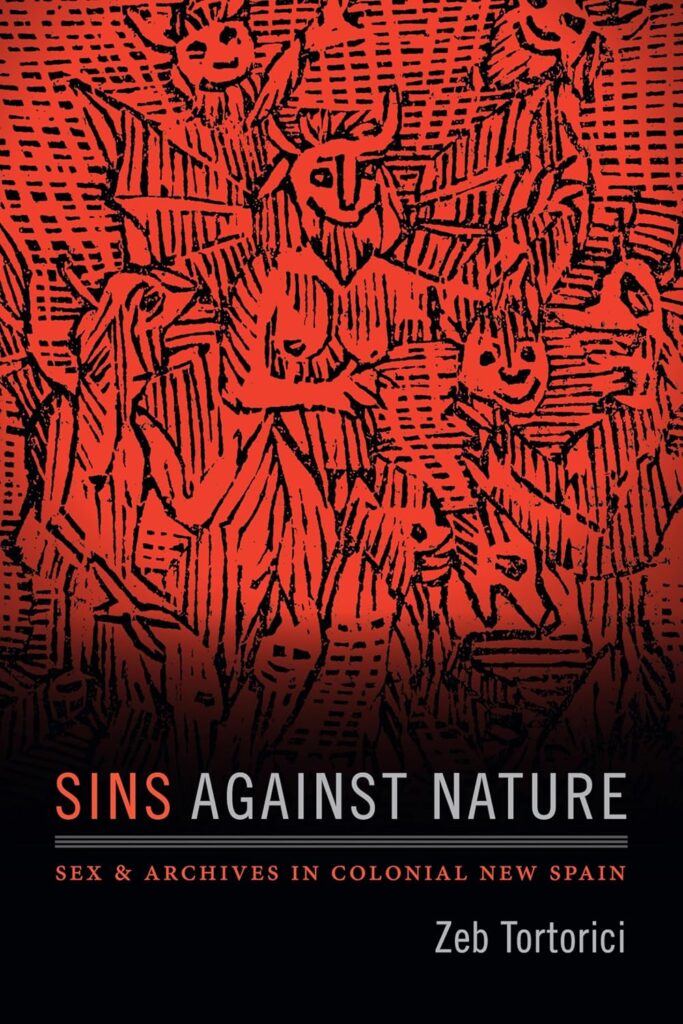

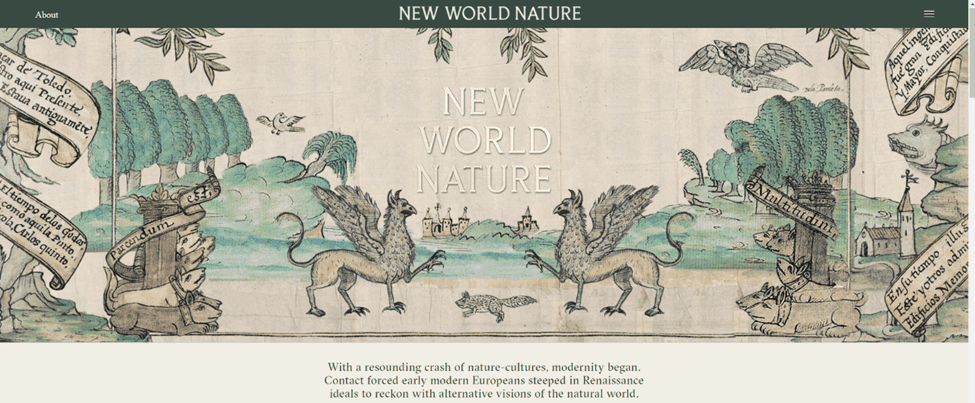

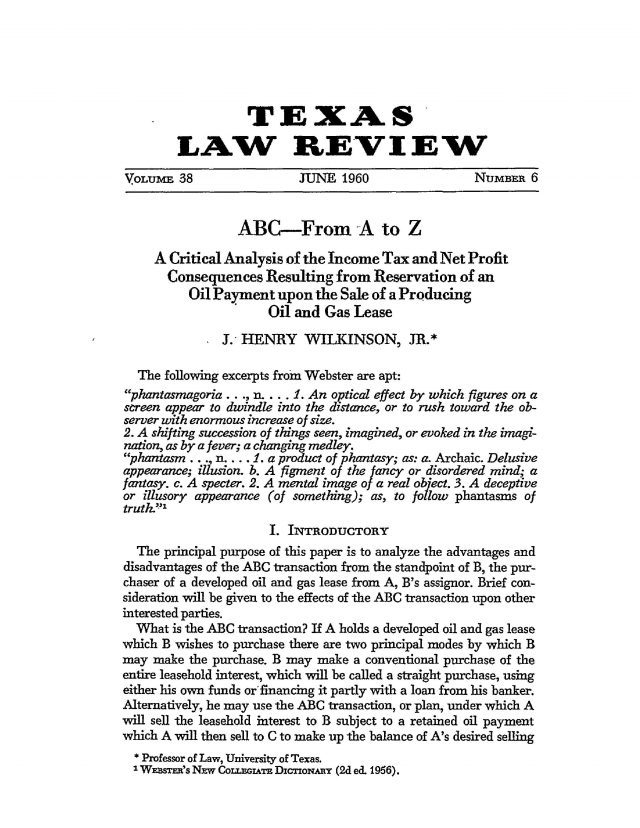

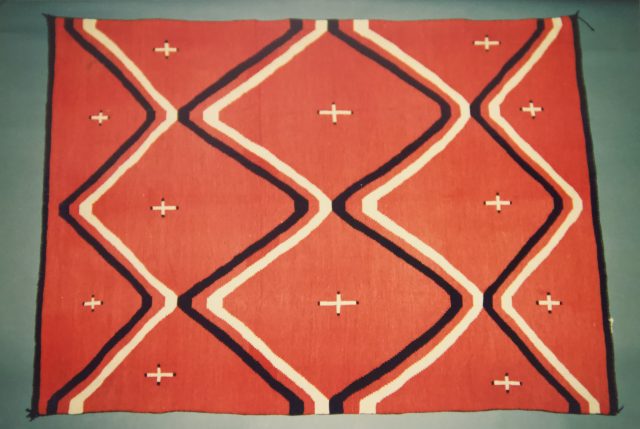

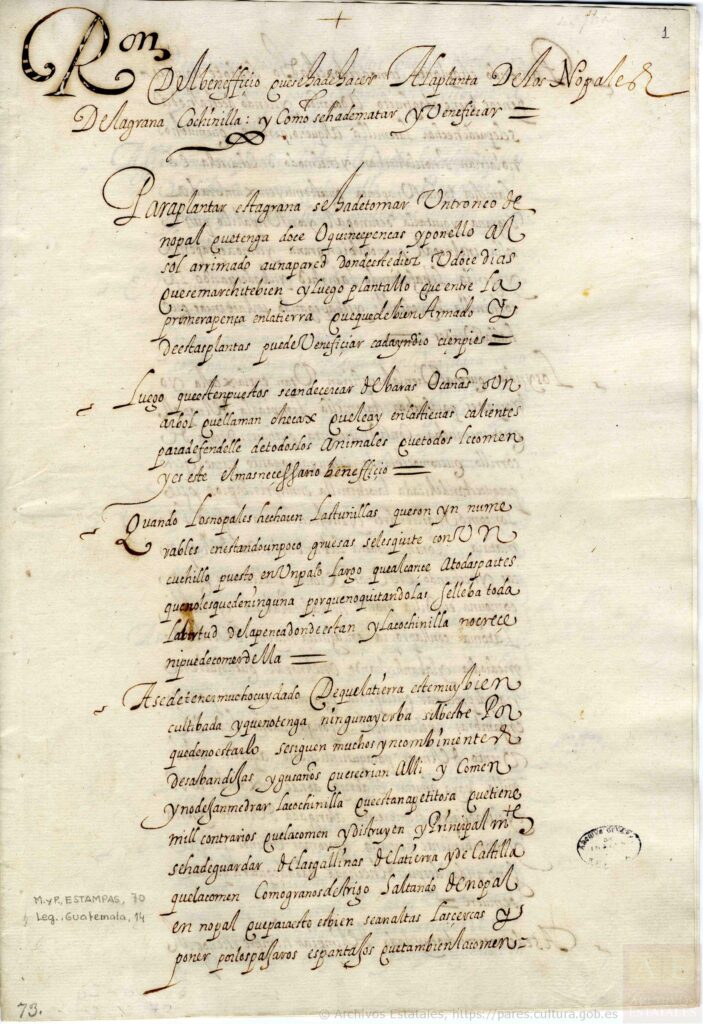

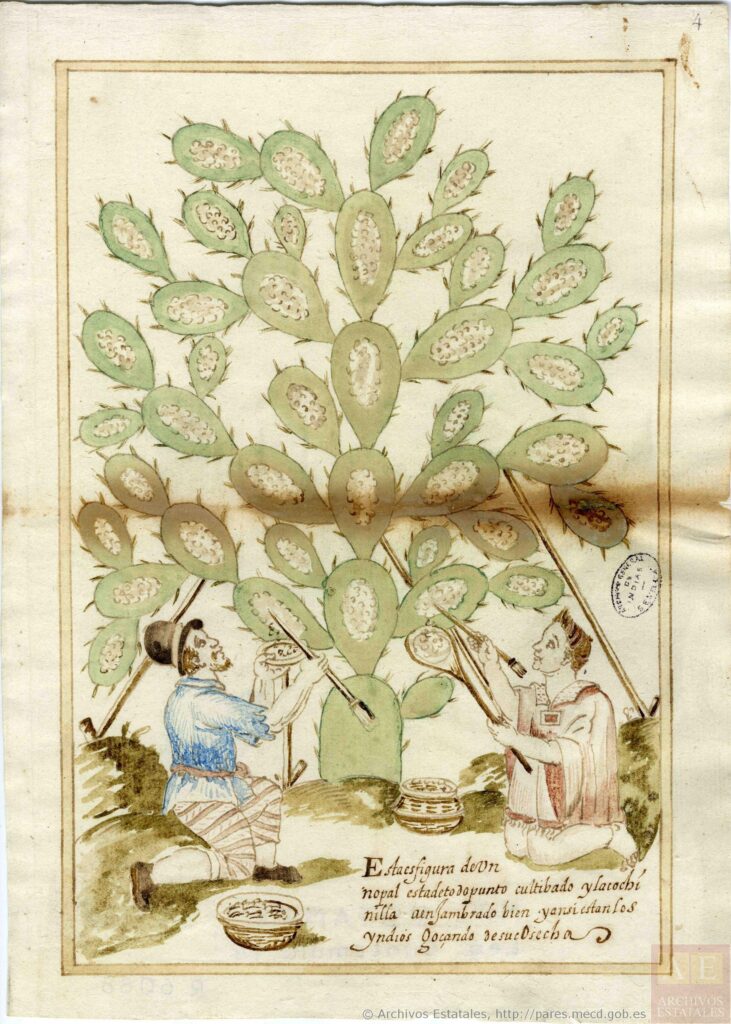

Hailed as one of the largest exports from Colonial Mexico, cochineal is a red dye obtained from parasitic insect females that sap nutrients from its plant host, the prickly pear cactus or nopal. Archival materials about this dye are quite scattered but there are a few illustrated documents (Fig. 3) that explain how Indigenous laborers in Central and Southern Mexico aptly managed parasites, plants, and the landscape to produce a highly specialized dye at a large scale. Like other scholars before me, I was interested in this striking visual culture. This led me to pursue a distinct archival journey from the one charted by the results I had collected in PARES.

I. Through the archival weeds

Among historians, the Spanish State archives are notorious for their cumbersome and restricted approach to digitization. Until only recently, researchers were strictly forbidden from taking photos at the AGI and therefore had to request the archivists to digitize sections of the archive, a process that could take many months if not years. Yet, it would be surprising for many to hear that the AGI and other Spanish state archives were pioneers in digitization, launching PARES online fourteen years ago. From then on, researchers and accidental historians like me have been able to use this archive at a scale, speed, and distance unimaginable three decades ago. For better or for worse, virtually every scholar of Colonial Latin America now begins their archival journey with digitized documents from PARES, which account at best for about 10% of their holdings. The AGI has now fully digitized diverse subsections such as Listas de Pasajeros (located in Contratación), Patronato, most of the bound books in the Gobierno Section (see Part 2), and a good portion of illustrations, maps, and material culture contained in Mapas, Planos y Estampas (MP-Estampas).

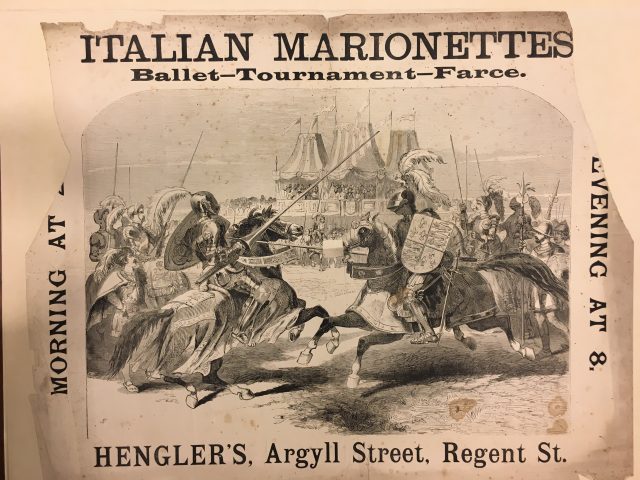

It is in MP-Estampas where one can find a charming drawing of a bison originally sighted in the Zuni town of Hawikuh. This drawing brings into view something I completely missed when I first read an illustrated report on cochineal production in Yucatán located in this same section. The cropped version of the bison drawing suggests it was taken from a larger document. To fully understand its purpose, it is crucial to refer to its original location in Patronato. In contrast, the seventeenth-century dye production report, featuring an image of a prickly pear, appeared self-contained. I initially only verified that its associated documents in Guatemala’s section were fully digitized. However, many months later, when I took the time to look more carefully at the documents in the original location of the report, I finally asked the most important question about the prickly pear image: Why was a document referring to prickly pears in Yucatán deposited in the papers of Guatemala?

Figure 3. “Dibujo de la obtención de la grana o cochinilla”, MP-Estampas, 70, Archivo General de Indias, 1620. The illustration of the prickly pear cactus (nopal) is part of a brief report detailing how to cultivate these plants so they could sustain cochineal, an insect parasite that bore one of the most valuable red dyes in the early modern world.

Through this archival discovery I learned that I should not take digitized items from PARES for granted. Our time as researchers at the AGI seems so precious that we tend to prioritize legajos (bundles of documents)that are only available to consult in situ. Yet, it is also important to read in tandem relevant digitized documents for they might lead us to different sections of the archive. This is especially relevant for sections at the AGI that archivists curated long after the documents came to the archive such as MP-Estampas or Patronato. When documents are plucked out of the original trail that brought them to the archive, it is easy to miss what was their original purpose and the creators behind them.

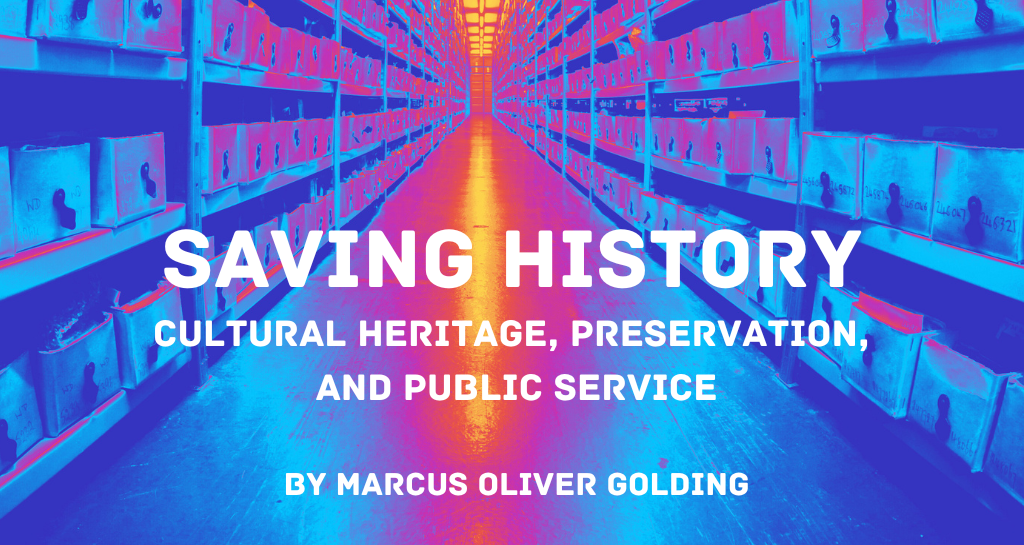

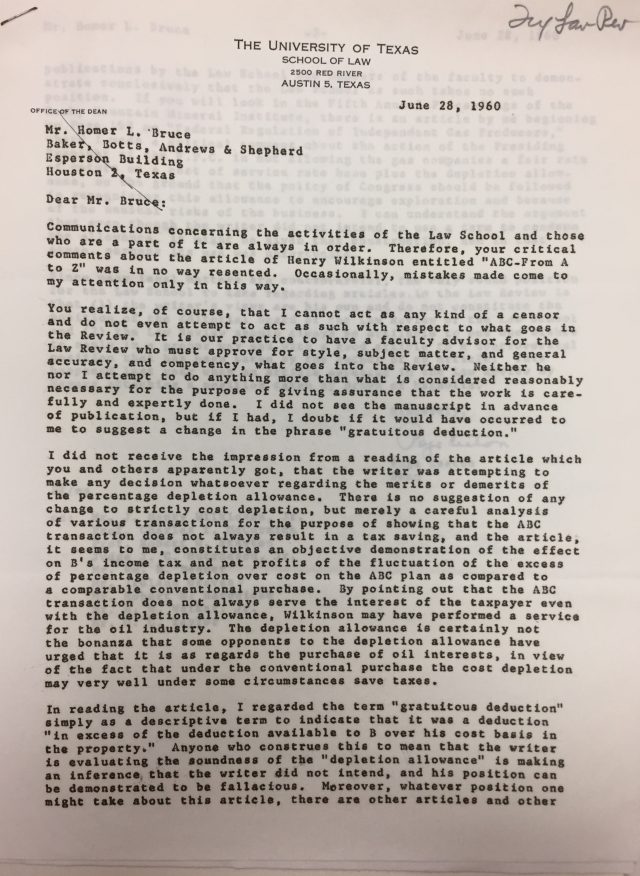

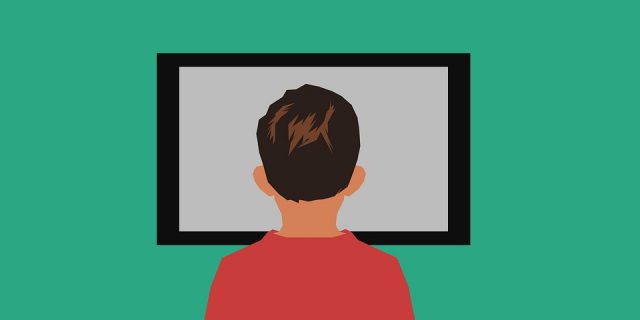

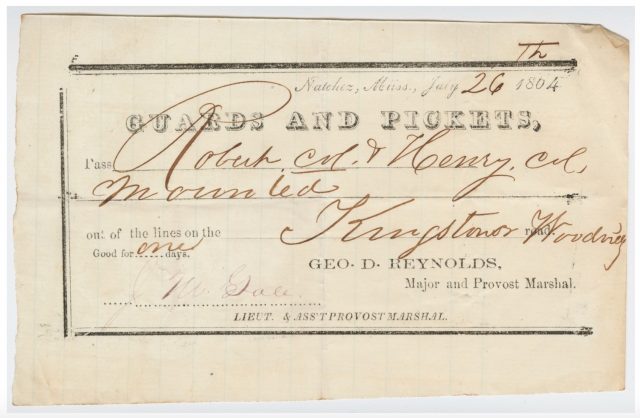

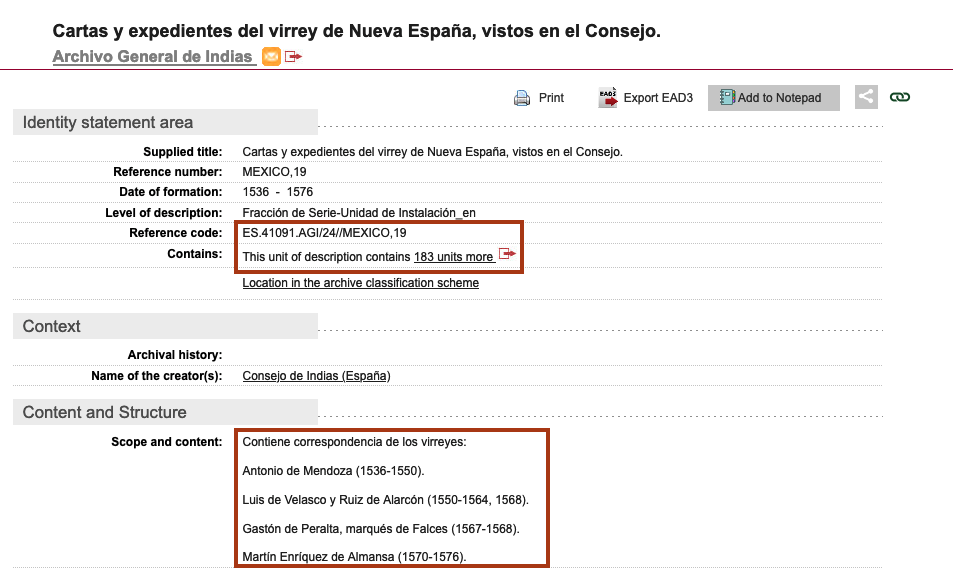

My lack of diligence in reading digitized documents was compensated by my stubbornness to find out more about prickly pears in the Yucatán Peninsula. Since the report was one of the first documents that caught my attention when I first articulated my dissertation project, I was determined to find more about it. Yet, when I looked for traces about prickly pears or dyes in Yucatán, my PARES search results were disappointing. This is not entirely surprising as Yucatán was considered a remotely communicated region during Spanish colonial rule. But my inability to find relevant documents about my inquiry was rooted in the heterogeneous cataloging of the archive, not its remoteness. That is, the level of description of each legajo varies greatly across sections. There are legajos that archivists have thoroughly, or at least decently described, thus allowing for easy identification of relevant documents amidst hundreds of folios. Others, like many legajos from the infamous miscellaneous section of Indiferente General, have just a broad identification label with a range of years, sometimes without any geographic attribution.

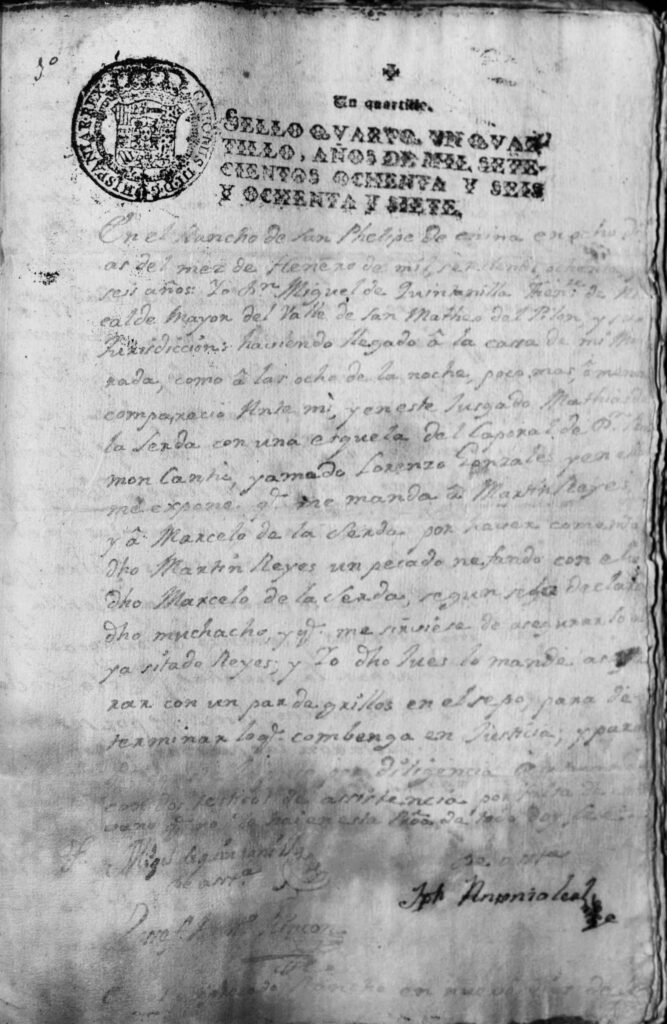

Figure 4. Comparison between two legajos with contrasting levels of description: The left one lists correspondence from different viceroys in New Spain and has been fully digitized and organized by year. The right one is only available to consult in situ and covers over two-hundred years of Council and Board reports.

I decided to immerse myself into the world of scantily described legajos and started to look for anything remotely related to Yucatán. To navigate the heterogeneous cataloging of the AGI, I established the main coordinates of my search in terms of geography –any jurisdiction related to colonial Yucatán; people: any colonial bureaucrat related to prickly pears and cochineal; time frame: three decades before or after 1620, the year of the report. I also relied on three strategies: 1) use print catalogs to understand the organization of different archival sections; 2) look for archival clues and references on expert literature; 3) ask for help from the authors or readers of expert literature.

These somewhat obvious strategies allowed me to find numerous fragments scattered across various legajos in the sections of Gobierno and Escribanía. While there were many days when I poured over dozens of pages thinking I had not found a single thread, I came to realize that I needed this time to get acquainted with the archive and the voices spread across its sections. It taught me how to ask the archive better questions and start using PARES not as a fishing net to simply see “what’s out there”, but as a navigational chart.

II. Labyrinth shortcuts

My weeks-long search for Yucatán’s prickly pears was mostly successful because the AGI has an extraordinary scholarly community that extends beyond its walls at the Cilla del Cabildo building. The famous 11 am coffee break that AGI users take every day certainly captures the enthusiasm and collaborative spirit surrounding the archive. Even if one does not partake in this ritual every day, it is incredibly easy to meet local and international scholars working on a wide array of topics related to the Spanish Empire and the early Americas. I was lucky enough to meet two researchers working on Yucatán that pointed me to key legajos and kept an eye for anything related to my dissertation. Additionally, the in-site archive’s library, the Hispanic American School Library, and the unmatched expertise of local scholars became the best way to learn about other Spanish archives and become acquainted with new historiographies.

To venture into the archival weeds of the AGI, more than patience or resourcefulness, one needs time and money. A prolonged stay in Seville is cost- and time-prohibitive for most scholars. Thus, making the most of each archival visit is vital. Over the past decade, the Spanish State Archives have made substantial changes that have increased their accessibility: longer operating hours, self-digitizing initiatives, an online system to book appointments, and the use of WeTransfer to send digitized files. And while their implementation at the AGI has been slow, I cannot stress enough how transformative some of these have been. They allow for better planning and use of time in the reading room. There is still plenty to improve especially on the cataloging front. In the second part of this piece, I will share a few tips that helped me improve my use of PARES and understand better their cataloging and organization.

Now that the AGI has loosened its strict policies about digitization, scholars will not need to spend as much time in Seville as older generations of historians did. Those of us who had the privilege of making a long research stay at the AGI might fear that the increase of short visits and indiscriminate use of cameras will erode the archive’s strong community. I do not know the AGI well enough to predict whether this will happen or not, but I do know that my colleagues’ love for coffee, gossip, and archival adventures is as timeless as the cover design of an AGI legajo. I do not expect to see a shortage of researchers sharing over coffee their grievances and archival finds any time soon.

Diana Heredia-López is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin. Originally trained as a biologist in Mexico, she has specialized in the history of science and colonialism since 2012. Her current research examines dye cultivation and commerce as a framework to investigate early modern Hispanic extractivism, knowledge production, and material culture.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.