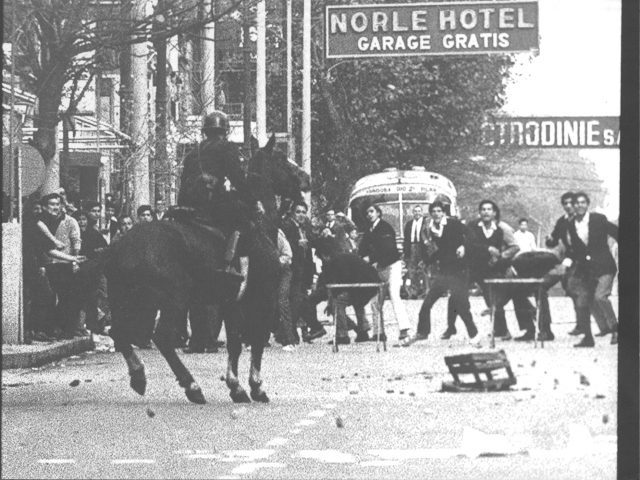

Windswept litter and flaming logs on asphalt. Backlit figures swaying to handmade percussive instruments and bongos. High school seniors from Colegio Nacional huddled for warmth on the sidewalk, resting foreheads on shoulders for brief shut eye. A neighboring group of teens hoisted Argentine flags that read Movimiento Estudiantil Liberación. They danced and chanted, their makeshift bonfire illuminating passionate faces, streaked with glittering green paint. Tens of thousands filled the park, mostly young and female. Their necks adorned with green handkerchiefs, an aesthetic marker of political and ethical community.

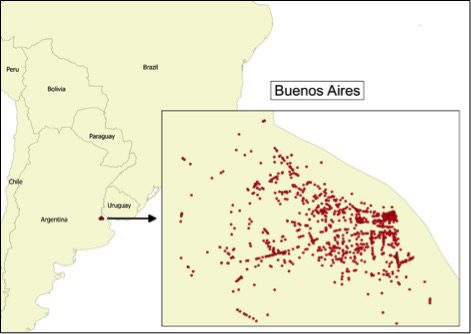

It was June 13, 2018 at around 10:30 pm when my mother and I joined the lively demonstration taking place outside of Argentina’s Congressional palace. After seeing intriguing images of the protest on the news, we were eager to witness the spectacle with our own eyes. We entered Plaza del Congreso just as the sun receded behind the neoclassical citadel in which the House of Deputies deliberated. Argentina’s lower house of Congress was voting on a bill that would decriminalize abortion in the first fourteen weeks of pregnancy. As political elites quarreled in their palace, a discussion that would last nearly twenty hours, protestors flooded the plaza outside to noisily advocate for the bill. Empty tour buses from countless distant provinces lined up along the avenues north of the blocked-off parameter. Inside the square, a cacophony of voices, symbols, and bodies deluged the space. Signs, banners, canopies, and tents exhibited slogans and logos of Tendencia Guevarista, Juventud Radical, Frente Popular Darío Santillán… and innumerable other left-wing political organizations.

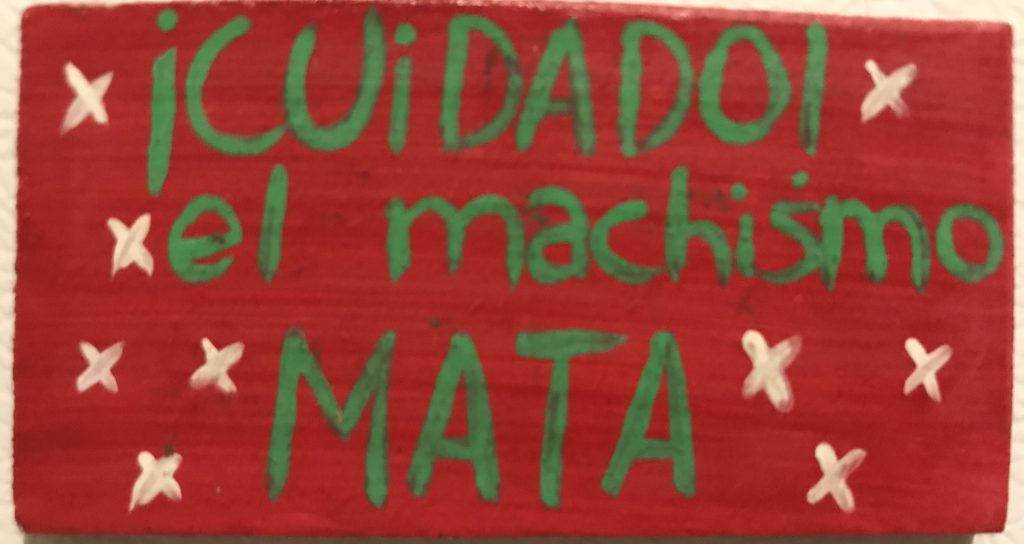

A loquacious group of teen artists sat on checkered blankets exhibiting sketches, magnets, and stickers for sale. My mother paid a blond boy with a nose-ring ten pesos for a magnet, which she handed to me, “un regalo – a present.” In bright red letters on a green background, it read “¡CUIDADO! EL MACHISMO MATA” (Careful! The patriarchy kills.) More than anything, I wanted a green handkerchief like everyone else, but no one seemed to know where they came from.

As a historian, I was impressed with the visual symbolism inherent in the handkerchiefs. I was immediately reminded of the photographs many of us have seen of elderly Argentine women defying a murderous military dictatorship. Las Madres de la Plaza de Mayo were middle-aged and elderly women who lost children and husbands to the military junta that ruled Argentina between 1976 and 1983. At great personal risk, these women met at the presidential palace every Thursday, beginning in 1977, to hold a vigil, wearing images of their missing kin on strings around their necks and plain white handkerchiefs on their heads.

It is reasonable to speculate that most of Las Madres de la Plaza de Mayo would not have considered themselves feminists, and it is even less likely they would have supported abortion rights. The historian Diane Taylor has pointed out that these women mobilized to defend their roles as mothers and wives, and they exploited traditional representations of femininity (purity and subservience to male family members) to mobilize shame. Even so, they remain national icons of feminine resistance in the public sphere.

Certainly, Las Madres paved the way for other female activist organizations, some of whom aligned themselves more directly with reproductive rights. For instance, Las Abuelas de la Plaza de Mayo consisted of women whose daughters or daughters-in-law were pregnant when detained by the military dictatorship. While searching for their missing grandchildren, this political group highlighted the military regime’s practice of kidnapping newborn infants for adoption into “loyal,” Catholic families. Margaret Atwood claims that this pro-natalist practice, with deep roots in Argentine history, was a fundamental inspiration for her novel The Handmaid’s Tale. Today, Las Abuelas continue to search for their grandchildren, many of whom are now in their late 30s or 40s and unaware of their biological heritage.

Las Abuelas de la Plaza de Mayo (via Wikipedia)

It goes without saying that today’s generation of activists in Buenos Aires operates in an entirely different historical context, with distinct political objectives. However, the symbolic implications of the pieces of cloth they wear on their bodies appear to acknowledge the role Las Madres and Abuelas played in legitimizing female activism. Now as then, Argentine women have shown they can provoke concrete political changes by assertively occupying public spaces.

As I think back to that Wednesday, I still remember wading through the sea of green, dazed and impressed with the demonstration unfolding. The closer to the palace we moved, the more boisterous and frenetic the crowd became. About fifty feet from the limestone and marble building, it became difficult to move. Here, banners rose fifteen feet into the air, most of them advertising Trosky-ist political parties, such as Movimiento Al Socialismo or Movimiento Socialista de los Trabajadores. The clamorous singing and drumming left my ears ringing after we painstakingly made our way out of the mosh pit. It was a rowdy rock concert with no central performer to orient the crowd and no security team to direct flows of human traffic. An overstimulation of sound, color, and corporal energy contrasted conspicuously with public displays of exhaustion nearby: teenagers sleeping in truck beds, on blankets, and against the iron fence circulating the square. A village of silent camping tents at the periphery of it all.

I spent only an hour or so at the demonstration, a small fraction of the time that most participants sacrificed to stand in the brisk winter night. The next afternoon, the Argentine Chamber of Deputies voted to decriminalize abortion by a narrow margin. This was an unprecedented victory for reproductive rights in a dominantly Catholic society and region of the world. The bill would have made Argentina just the third Latin American nation (after Cuba and Uruguay) to decriminalize abortions, and analysts speculated as to the effects this would have on reproductive rights transnationally. Unfortunately, the victory in the House of Deputies subsequently galvanized a counter mobilization of pro-life Catholics all over the nation. Even Argentine-born Pope Francis spoke out to condemn the legislation, and the country’s Senate ultimately defeated the bill in August. All the same, the bill’s narrow margin to victory and the movement’s prominent visibility were remarkable for a conservative country on a continent where abortion rights are the exception. In any case, the extraordinary June demonstrations deserve to be remembered for their historical and social significance in the larger trajectory of the Argentine feminist movement, rather than the legislative defeat that followed.

For more on gender in Argentina, see Diana Taylor, Disappearing Acts: Spectacles of Gender and Nationalism in Argentina’s “Dirty War,” (Durham: Duke University Press, 1997).

You May Also Like:

UT Gender Symposium: Women’s Bodies and Political Agendas

Women and Social Movements in the United States, 1600-2000