On Wednesday, September 10th, I moderated a webinar with notable immigration historians who situated the current presidential administration’s policing, detainment, and deportations of marginalized immigrants in conversation with the past.

“How Did We Get Here? U.S. Immigration Historians Respond” brought together leading scholars of U.S. immigration history to reflect on the current environment of fear among immigrant communities in the United States. Panelists traced the evolution of immigration law and enforcement from the late 19th century to the present, highlighting the structural forces that have shaped the experiences of economic migrants, political and environmental refugees, and asylum seekers. As one presenter, Dr. Kang, asserted, “We have always been here.” Immigrant communities–both authorized and unauthorized–have always lived under constant fear that a change in administration and policy could upend their lives.

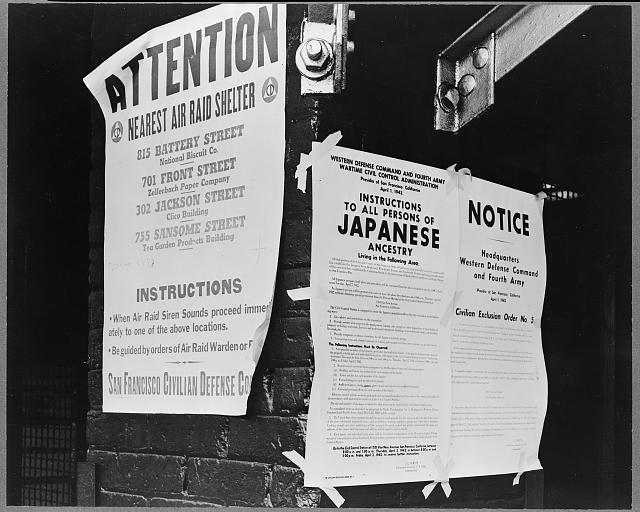

In the week leading up to the webinar, three significant events underscored the intensifying pressures on immigrant communities. On September 4th, 2025, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) carried out the largest immigration raid in U.S. history at the Hyundai electric battery plant in Ellabell, Georgia, arresting 475 people–most of them South Korean nationals. Many reportedly had legal permission to work in the United States, yet ICE operations separated families, and children returned from school to find their parents had disappeared.[1] The next day, the Justice Department’s Board of Immigration Appeals ruled that immigration judges no longer had authority to grant release on bond.[2] This decision made detention mandatory for immigrants awaiting hearings, vastly expanding incarceration in already overcrowded detention centers and funneling even more public money to private prison companies.

Days later, on September 8th, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a federal ruling that had barred roving immigration stops in Los Angeles. In a 6-3 decision, the Court held that race, ethnicity, or speaking Spanish could be considered “relevant factors” in such stops, alongside factors such as where people work or congregate.[3] The ruling appeared to sanction racial profiling, granting ICE wide discretion to detain individuals based on appearance, language, and perceived class. In her dissent, Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor warned that this decision entrenches a system in which “the Government can seize anyone who looks Latino, speaks Spanish, and appears to work a low-wage job.”[4]

The webinar featured Professors Maddalena Marinari (Gustavus Adolphus College; President of the Immigration and Ethnic History Society); Deborah Kang (University of Virginia); Sergio González (Marquette University); and Carl Lindskoog (Raritan Valley Community College) to speak to the UT Austin community. Each scholar spoke from their own expertise, such as 20th-century immigration policy (Marinari), the growth of immigrant policing (Kang), the rise of detention prisons (Lindskoog), and the resistance efforts by immigrant communities and their citizen allies in what is known as the U.S. Central American Sanctuary Movements (González).

The event was co-hosted by the Frontera Scholars Collective, the Department of History, the Department of American Studies, the Center for Asian American Studies, and the Latino Studies program. The event was also organized in collaboration with Dr. Cortez’s course, “Immigration and Ethnicity.”

Jonathan Cortez, Ph.D. is currently an Assistant Professor of History at The University of Texas at Austin. Their current manuscript, A Nation of Immigration Camps, details the history of vernacular and federally funded immigration camps along the U.S.-Mexico border from the late 19th century to the late 20thcentury.

[1] Lydia DePillis and Hamed Aleaziz,”Georgia ICE Raid Netted Workers With Short-Term Businness Visas,” New York Times, September 12, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/09/12/business/economy/hyundai-raid-worker-visas.html#:~:text=Hyundai%20ICE%20Raid%20Detained%20Workers,raid%2Dworker%2Dvisas.html

[2] Josh Gerstein and Kyle Cheney, “Immigration appeals court expands mandatory detention for millions,” Politico, September 5, 2025.

[3] Lawrence Hurley, “Supreme Court lifts limits on roving immigration patrols in Los Angeles area,” NBC News, September 8, 2025. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/supreme-court/supreme-court-immigration-stops-los-angeles-rcna223845

[4] American Immigration Council, “How the Supreme Court’s Latest Decision Clears the Way for Racial Profiling During Immigration Raids,” September 9, 2025. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/blog/supreme-courts-decision-racial-profiling-immigration-raids/

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.