Doing History Online and In Public

Millions of tweets and millions of state documents. Intimate oral histories and international radio addresses. Ancient pottery and yesterday’s memes. Historians have access to this immense store of online material for doing research, but what else can we do with it? In Spring 2018, graduate students in the Public and Digital History Seminar at UT Austin experimented with ways to make interesting archival materials available and useful to the public; to anyone with access to a computer.

Links to their projects can all be found below on this page.

We built these digital, public projects in four main steps.

First, with the help of UT librarians, the students identified collections related to their research that were not yet available to the public. These collections of documents come from the many wonderful archives on our campus: the Harry Ransom Center, the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, the Perry-Castañeda Library, the Briscoe Center for American History, and the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection. Then we digitized them.

Second, we each wrote a series of blog-essays to share our archival finds with the public. Each blog is meant to show something historically significant about our documents and to open them up in ways that any curious reader, without any background in the subject, can understand and appreciate.

Third, we wrote lesson plans based on our documents to allow educators at the K-12 and college levels to bring our archives into their classrooms.

Finally, we each built a website to introduce our topics, to share our digitized documents, and to make our blogs and lesson plans openly available.

Here are the results:

Qahvehkhaneh: Reading Iranian Newspapers: by Andrew Akhlaghi

The coffeehouse, qahvehkhaneh, was an important political and cultural institution in Iran. As men drank coffee, played backgammon, and discussed business, they also listened to impassioned pleas for democracy and reform from newspapers published in the Ottoman Empire, Russian Caucasus, and British India, smuggled into Iran and read aloud. This qahvehkhaneh is meant to spread the issues of one newspaper, Etella’at, to those curious about Iran.

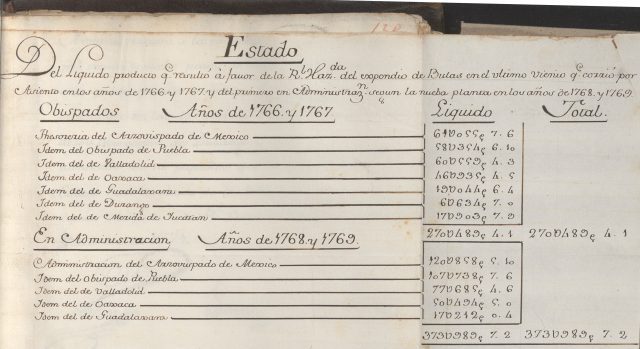

Bureaucracy on the Ground: the Gálvez Visita of 1765: by Brittany Erwin.

This project examines the localized consequences and on-the-ground implications of the royal inspection, or visita general, administered by José de Gálvez in New Spain from 1765-1771.

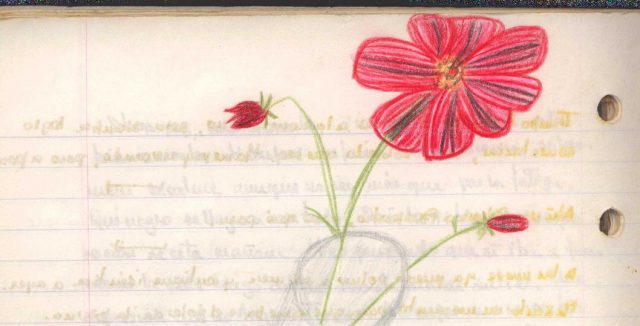

After the Silence: María Luisa Puga and the 1985 Mexico City Earthquake by Ashley Garcia

María Luisa Puga (1944-2004) was a talented Mexican novelist from the Post-Boom movement whose personal notebooks, manuscripts, correspondence, and related documents are held in the Benson Latin American Collection. On this site you will find digitized selections from Cuaderno 118, which contains both Puga’s coverage of the earthquake that struck Mexico DF (now Mexico City) in 1985 and her reflections on those original pages, written in 2002.

Building a Jewish School in Iran: The Barmaïmon-Hamadan Manuscript by Isabelle Headrick

Where do you go when you want to change the world? For Isaac and Rebecca Bassan in 1900, the destination was Hamadan, Iran, to establish a French-language, Jewish school for the small Jewish community in that city. About fifty years another teacher at the school, Isaac Barmaïmon, wrote an 81-page manuscript that describes the first twenty years of the school’s existence.

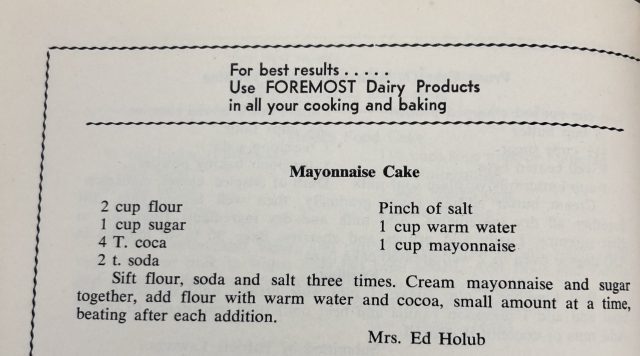

Food Migrations: Texas Czech Culinary Traditions by Tracy Heim

Texans with Czech heritage have been able to preserve their culture in America through organizations, cultural events, church groups, and especially through food. Two books of recipes and other documents contextualize the process of migration into life in Texas and create a framework for understanding the Texas Czech culture.

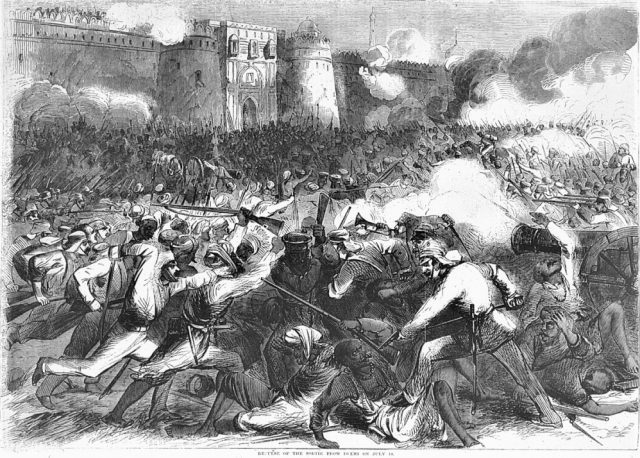

Indian Revolt of 1857 by Anuj Kaushal.

South Asia witnessed an event during 1857 which altered the history of India, Britain, and the British East India Company. The event, known as a mere “mutiny” by the British and as an anti-colonial revolt by Indians, was reported in the English language press around the world.

The Road to Sesame Street by Peter Kunze

The Road to Sesame Street features government documents tracing the development of the Public Broadcast Act of 1967, the landmark legislation that established the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, PBS, and NPR. Using materials from the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library in Austin, this project provides a behind-the-scenes view of the power players, interest groups, and decisions that laid the groundwork for American public media.

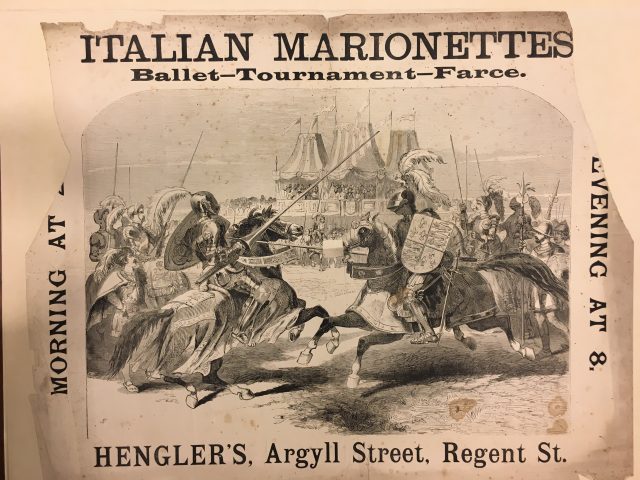

Animating Italian Immigration: Sicilian-American Puppetry by Megan McQuaid.

Attending a puppet theatre performance with familiar characters acting out well-known stories gave some Italians living in New York City a regular taste of the homeland they had left behind.

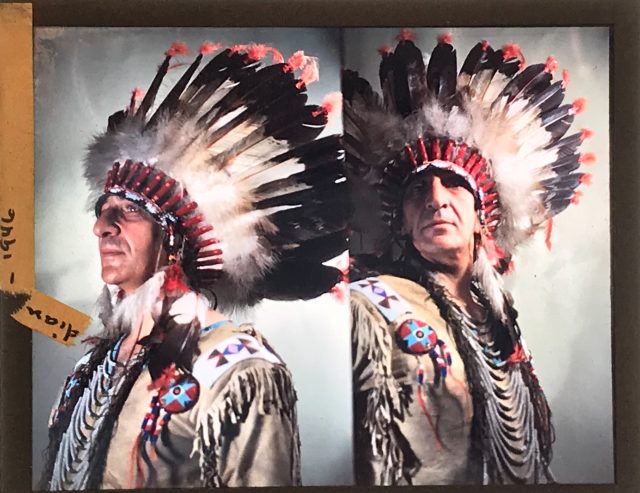

Frederic Allen Williams: Citizen-Artist with a Magic Lantern by Jesse Ritner

Frederic Allen Williams (1898-1955) was a prominent sculptor, lecturer, intellectual, and rodeo rider based in New York City, where he became known for his talks on Native American art, illustrated with magic lantern slides, which he gave in his midtown studio near the then recently built Museum of Modern Art.

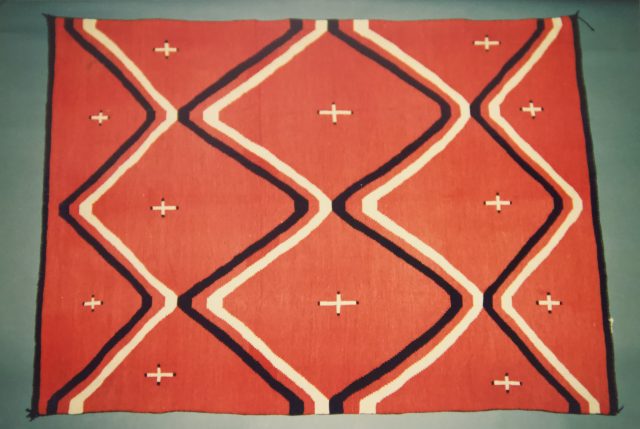

Woven Into History: Living Cultural Fabrics by Alina Scott

The nineteenth and twentieth-century Navajo rugs in this collection aims to provide a platform for respectful collaboration and discourse to recenter the discussion of Navajo culture and commodity production around them and to diversify traditional conversations about Navajo textiles and their communities.

Mercenary Monks by Jonathan Seefeldt

These texts are windows into a thriving monastic world whose varied activities included: raising mercenary armies, caring for widows and child brides, providing credit and other banking services, collecting tax revenue from farmers, providing merit and prestige to an emerging merchant class, and asserting a (short-lived) form of political independence.

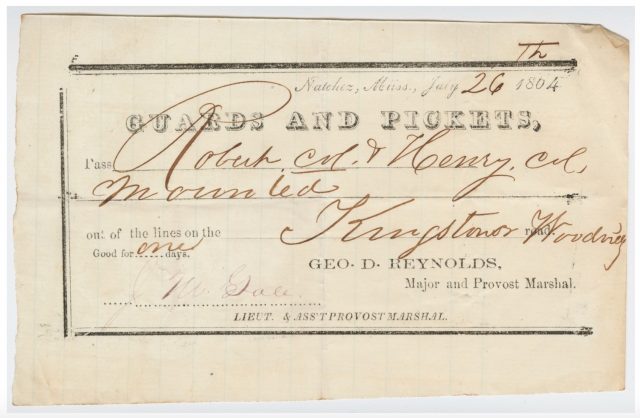

Guards and Pickets: The Paperwork of Slavery by Gaila Sims.

The documents in this collection provide a glimpse into the paperwork created to control the movement and relationships of the enslaved, as well as the financial documentation used to make money off the institution of slavery.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the following people for sharing their expertise in digital and public history with us: Dale Correa, Liza Talbot, Ian Goodale, Stephanie Malmros, Christina Bleyer, Albert Palacios, Andrea Gustavson, Elizabeth Gushee, Astrid Ruggaldier, Penne Restad, and Stacy Vlasits.