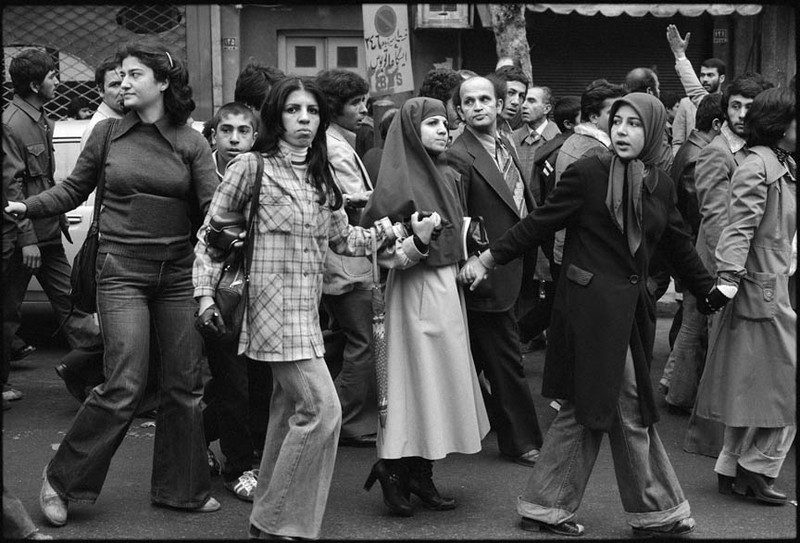

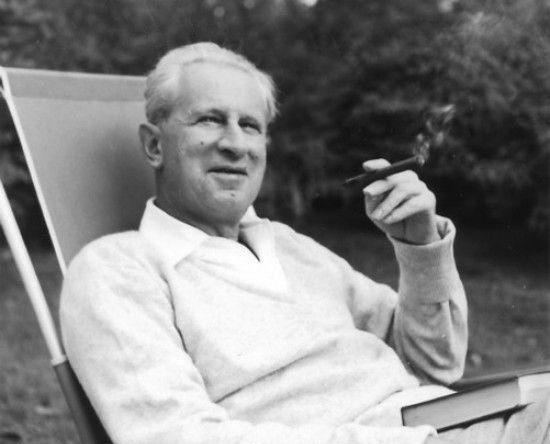

Dulles with President Eisenhower in 1956 (via Wikipedia)

To experts on the history of U.S. foreign policy, the Dulles brothers’ service during Dwight D. Eisenhower’s presidency marks an important watershed in the evolution of American interventionism. In the context of brewing conflict with the Soviet Union, Eisenhower’s administration aimed to protect developing countries of the “Third World” from being converted to Communism. However, as recovery efforts following World War II mobilized international diplomatic efforts to broker world peace, U.S. officials were reluctant to deploy troops abroad. John Foster Dulles was Eisenhower’s secretary of state during this time. His brother, Allen Dulles, served as director of the recently founded Central Intelligence Agency. Together, the Dulles brothers used this agency to eliminate perceived communist threats in the Third World through covert operations, establishing a powerful precedent for “regime change” as foreign policy strategy.

What fewer scholars and policy enthusiasts know is that the Dulles brothers were products of an elite political family with a strong internationalist tradition. John Foster Dulles’ personal papers, stored at his alma mater Princeton University, exhibit how the eldest brother’s upbringing and family network, consisting of diplomats, missionaries, and international lawyers, influenced his developing world view. This is particularly the case with his maternal grandfather, John W. Foster, a prominent patriarchal presence during Dulles’ childhood. Ideological continuity between Foster and his oldest grandson is evident in their comparable career paths, their methods of preparing subsequent male generations, and their published texts and speeches which analyze the role of U.S. foreign policy in international affairs.

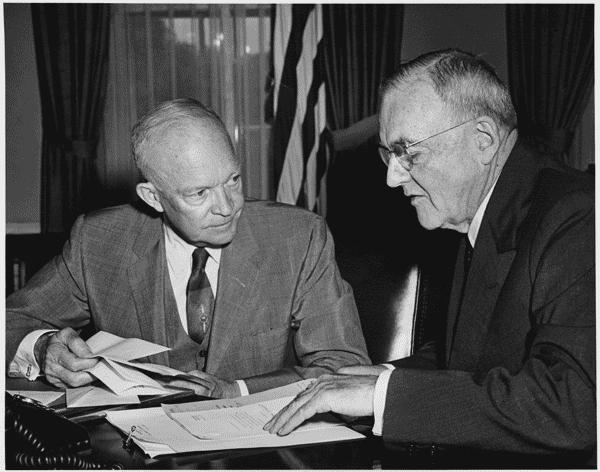

John W. Foster, Secretary of State under President Benjamin Harrison (via Wikipedia)

Dulles’ personal papers suggest that he modeled his career after that of his grandfather. Foster had also served as secretary of state, at the end of President Benjamin Harrison’s administration. He inhabited this role during the fall of the Hawaiian monarchy in January 1893, an event that led to U.S. annexation of the archipelago. Foster then left political office to pioneer U.S. corporate legal practices and distinguish himself as an international diplomat. Notably, he mediated negotiations at the close of the First Sino-Japanese War and drafted the Treaty of Shimonoseki, signed on April 17, 1895. Dulles’ career subsequently followed a similar path. He also became an international corporate lawyer, partially through his grandfather’s connections, at the elite law firm Sullivan and Cromwell LLC. As partner at this firm, Dulles represented powerful U.S. corporations with vested interests abroad, such as the United Fruit Company. Dulles simultaneously cultivated a long-term career in international diplomacy, serving as secretary to the Economic Reparations Committee at the Treaty of Versailles and later as delegate to the San Francisco Conference which established the United Nations.

Continuity is also evident in the two figures’ strategies for patriarchal mentorship. While Dulles was still a child, he spent his summers at his grandfather’s house on Henderson Harbor in upstate New York. Very early most mornings, Foster took his grandsons fishing. On these excursions, the Dulles brothers learned how to catch their own lunch and cook over an open fire. They ate as they listened to their grandfather’s stories of his experiences abroad, often in the company of distinguished guests such as William Howard Taft, Andrew Carnegie, or Bernard Baruch. These trips taught the boys that self-reliance was a masculine virtue while, at the same time, integrating them into a network of white male elites. Dulles later applied similar methods to raising his sons, taking them on month-long sailing voyages up the Canadian coastline, where they learned to navigate by starlight and catch their own food. For both Foster and Dulles, traveling by water was a fruitful exercise in battling uncontrollable elements, which they believed benefitted male members of subsequent generations.

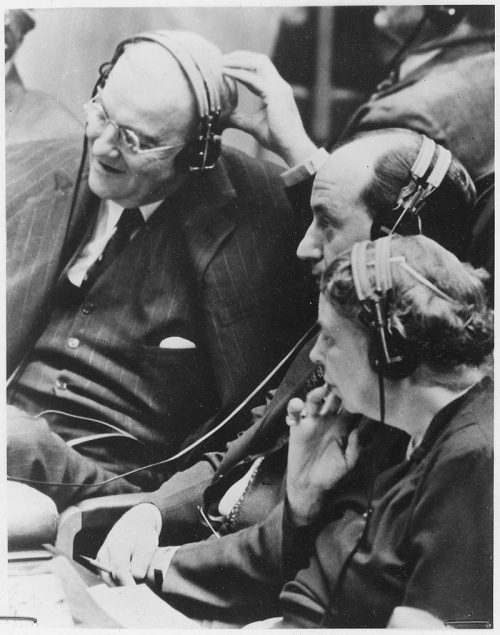

Eleanor Roosevelt, Adlai Stevenson, and John Foster Dulles at the United Nations in New York City (via National Archives and Records Administration)

Dulles’ and Foster’s published texts and speeches exhibit their shared value of an activist, and interventionist, American foreign policy. Foster had written two books on U.S. diplomacy, both treasured by his progeny. The first of these, A Century of American Diplomacy: Being a Brief Review of the Foreign Relations of the United States 1776-1876, published in 1900, recounted a diplomatic history of the United States, with emphasis on the functions of the state department. Foster exhibited profound enthusiasm for the foresighted genius of the founding fathers and for the “honorable position” characteristic of U.S. diplomacy. The closing chapter examined the importance of the Monroe Doctrine to U.S. foreign policy. President James Monroe first articulated the Doctrine in an address to Congress in 1823. It established U.S. rights to exclusive influence over the whole Western Hemisphere in response to colonial ambitions of the Holy Alliance (Russia, Prussia, and Austria) following the decline of the Spanish Empire. Like his grandfather, Dulles viewed the Monroe Doctrine, as the “most essential expression” of American foreign policy. During the Cold War, Dulles drew parallels between the threat of the Holy Alliance and the one posed by the Soviet Union. Despite writing at dramatically different times in U.S. history, both Dulles and his grandfather interpreted the Monroe Doctrine to sanction American use of force in the interest of preventing the spread of European political influence.

Dulles’ history goes to show how an analysis of his service as secretary of state, or the C.I.A. operations he sanctioned, are not sufficient for understanding how U.S. policymakers justified intervention during the Cold War. The secretary’s relationship with his grandfather and his understanding of U.S. history shaped his worldview in significant ways. It is important to pay attention to the durability of intellectual and ideological influences that inform the most prominent individuals who execute foreign policy in the United States. This is especially so since American society still grapples with ideological convictions regarding gender, class, religion and nationality that echo sentiments advanced by Dulles and his contemporaries. Such intellectual and ideological understandings will continue to have a dramatic impact on the U.S. foreign and domestic policies. Scholars would do well to recognize and wrestle with the durability of these beliefs, if they believe history might help Americans understand the many ramifications sure to emerge as a result.

You may also like:

Mark Battjes reviews Worldmaking: The Art and Science of American Diplomacy by David Milne (2015)

Michelle Reeves reviews For the Soul of Mankind: The United States, the Soviet Union, and the Cold War by Melvyn P. Leffler (2008)

Mark A. Lawrence on the Soviet view of U.S. intentions after WWII

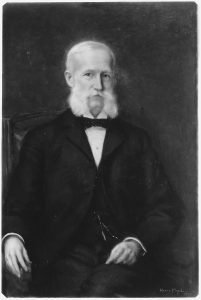

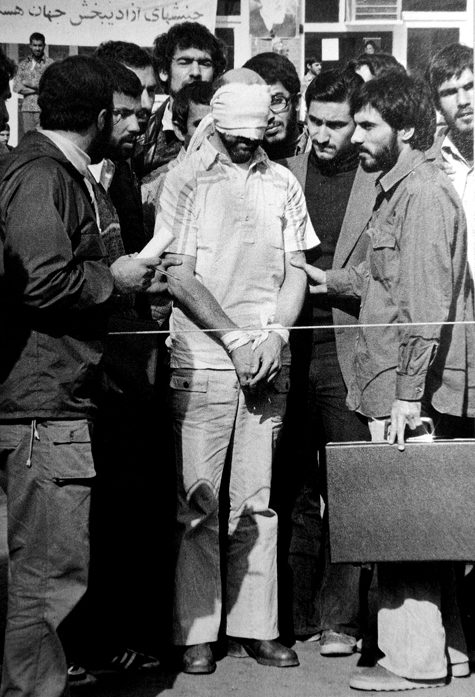

semi-animated sequence that explains American involvement in Iran following the 1953 CIA-orchestrated coup that deposed democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh in favor of Shah Muhammad Reza Pahlavi.

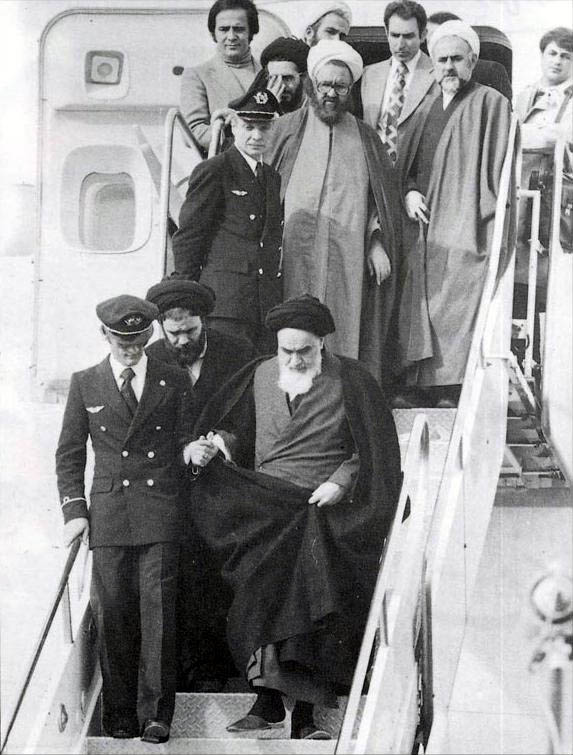

semi-animated sequence that explains American involvement in Iran following the 1953 CIA-orchestrated coup that deposed democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh in favor of Shah Muhammad Reza Pahlavi. by a mob that took the embassy employees hostage. Initially, hopes were that Khomeini’s government would step in and release the hostages, as they had done previously, when the embassy was breached during the previous summer, but government officials instead sanctioned the hostage taking. The embassy employees would eventually be held in captivity for 444 days. The Iranian government agreed to release them on January 20, 1981—inauguration day in the U.S.—and held their plane on the tarmac at Tehran’s Mehrabad Airport until after Ronald Reagan had been sworn in as president. This was perceived as a final snub to outgoing president Jimmy Carter, who had stood beside the Shah in Tehran just three years earlier and proclaimed Iran “an island of stability in the Middle East.”

by a mob that took the embassy employees hostage. Initially, hopes were that Khomeini’s government would step in and release the hostages, as they had done previously, when the embassy was breached during the previous summer, but government officials instead sanctioned the hostage taking. The embassy employees would eventually be held in captivity for 444 days. The Iranian government agreed to release them on January 20, 1981—inauguration day in the U.S.—and held their plane on the tarmac at Tehran’s Mehrabad Airport until after Ronald Reagan had been sworn in as president. This was perceived as a final snub to outgoing president Jimmy Carter, who had stood beside the Shah in Tehran just three years earlier and proclaimed Iran “an island of stability in the Middle East.” intelligence officials who uncover the true identity of the “film crew” just as they prepare to board the plane, an unnecessary assault against a female gate agent who lacks the keys to reopen the gate once the plane is ready for departure, and an over the top chase scene involving revolutionary guards in late 1970s Chevrolets who manage to keep pace with a 747 thrusting down the runway for takeoff.

intelligence officials who uncover the true identity of the “film crew” just as they prepare to board the plane, an unnecessary assault against a female gate agent who lacks the keys to reopen the gate once the plane is ready for departure, and an over the top chase scene involving revolutionary guards in late 1970s Chevrolets who manage to keep pace with a 747 thrusting down the runway for takeoff.  character in the film rises above the level of caricature, Sahar (Sheila Vand), the Taylor’s housekeeper. Her discomfort with the presence of the Americans in the household is eventually outweighed by her discomfort with the local komiteh—the ubiquitous neighborhood “committees” that sprang up after the Revolution to police the capital block by block—who become suspicious of the ambassador’s long-term “guests.” Sahar is eventually shown fleeing to neighboring Iraq, but it’s never quite explained why she needs to flee and what the repercussions of her remaining in Iran would have been. The scene is, instead, played tongue in cheek, meant to encourage audiences to roll their eyes at the thought of Iraq representing “safety.”

character in the film rises above the level of caricature, Sahar (Sheila Vand), the Taylor’s housekeeper. Her discomfort with the presence of the Americans in the household is eventually outweighed by her discomfort with the local komiteh—the ubiquitous neighborhood “committees” that sprang up after the Revolution to police the capital block by block—who become suspicious of the ambassador’s long-term “guests.” Sahar is eventually shown fleeing to neighboring Iraq, but it’s never quite explained why she needs to flee and what the repercussions of her remaining in Iran would have been. The scene is, instead, played tongue in cheek, meant to encourage audiences to roll their eyes at the thought of Iraq representing “safety.”