by Jimena Perry

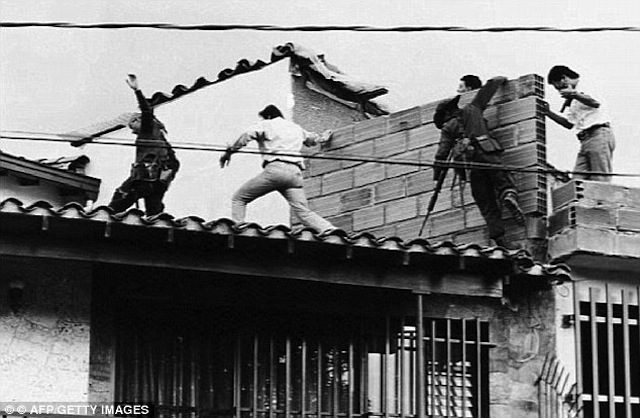

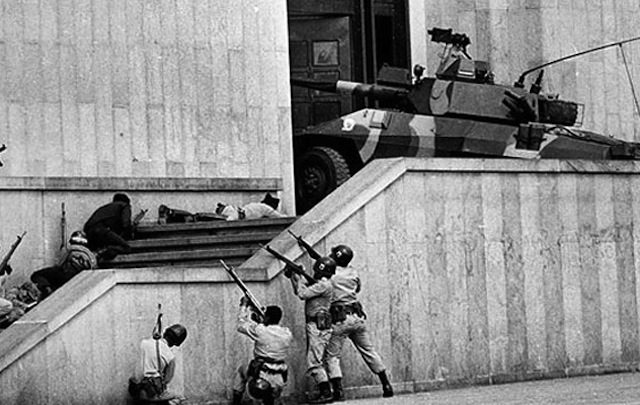

In July 2017, as part of my dissertation research, I had the opportunity to participate in an assembly of the Association of Victims of Granada (Asociación de Víctimas de Granada, ASOVIDA), in Colombia. This organization is composed of the survivors of the violence inflicted by guerrillas, paramilitaries, and the National Army during the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s. ASOVIDA was legally created in 2007 after three years of victims organizing, learning about their rights, and finding ways to prevent brutalities from happening again. Since the early 2000s, amidst the ongoing armed conflict in Colombia, the people of Granada began a process of awareness, prevention, and production of memories of the atrocities they experienced. To this day, the members of ASOVIDA gather on the first Saturday of each month to talk about their concerns as victims, to participate in community decisions, and to continue with their grieving and reparation process.

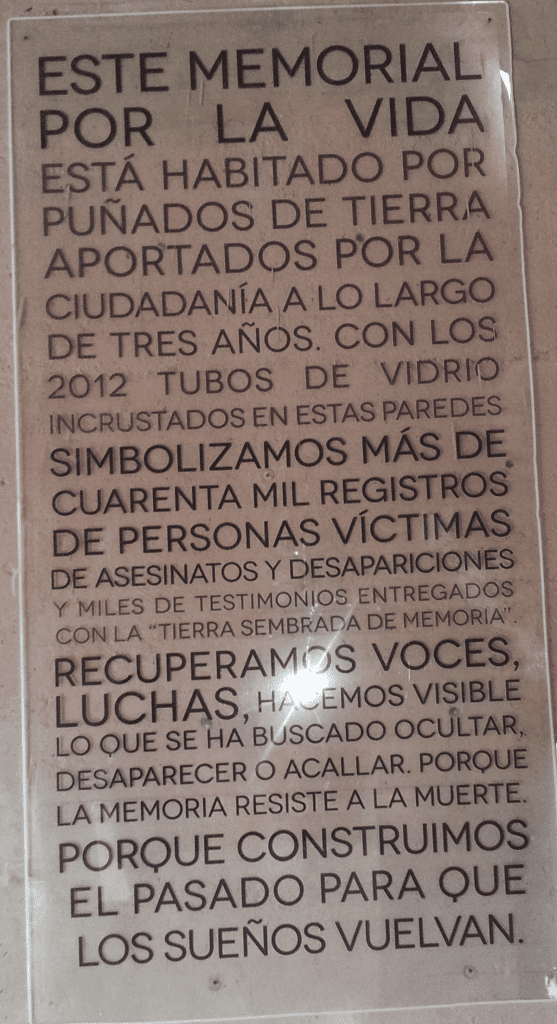

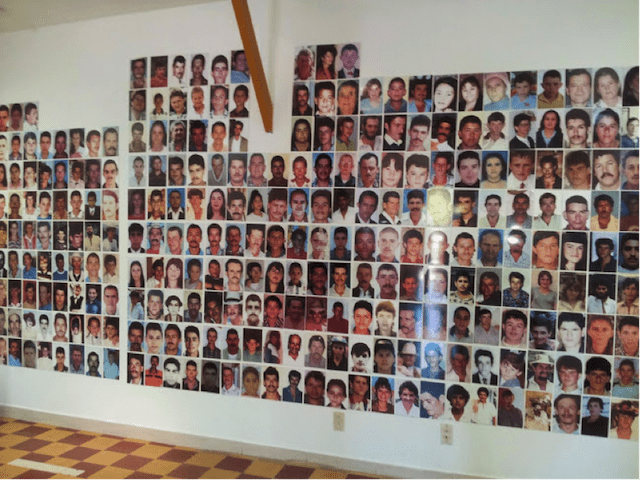

My dissertation is about the production of historical memories about the armed conflict in Colombia, including institutions like ASOVIDA and The Hall of Never Again, a space for remembering and honoring the victims of massacres, disappearances, targeted killings, bombings, and other forms of violence in Granada. Therefore, ASOVIDA´s president asked me to present my project before the assembly. She wanted me to tell the community why I am interested in ASOVIDA and the Hall, what I am going to do with the information gathered, and what benefits my work could bring to them. ASOVIDA´s president requested my presence at the assembly because some of my primary sources are the contents of so-called bitácoras, notebooks designed to make the victim´s grieving process easier. In these texts, one can read mothers talking to their children, husbands to their wives, brothers to sisters, children to their parents, and other family members remembering their departed loved ones. The bitácoras become both objects to be exhibited and historical sources for studying the violence endured by a particular person or family and how they survived. Bitácoras also provide an account of the story and character of the dead person, why he or she was important and help the public and visitors of the Hall to learn about local history and to link the survivors to community reconstruction processes. They are intimate accounts of the survivor’s feelings along with very personal stories, consequently, using them requires an ethical commitment and a deep respect towards their authors.

When requested to present my project before the assembly, my first reaction was surprise. Why should I do this? If the bitácoras are part of the Hall of Never Again´s exhibit they are already public records; they are meant to be read, but when I thought carefully about the request, I realized that the authors had reasonable suspicions. I am an outsider, a researcher who comes and goes; I have not suffered violence in the same way, and there I am using their cherished stories for an academic endeavor.

It made even more sense when I saw the inhabitants of Granada at the assembly´s meeting. Regular people working to achieve peace in their town looked at me with curiosity. They wanted to know who was I and what was I doing there. Seeing all those people, interested in finding peace for themselves, their families, and town, I understood that academic research becomes secondary to dealing with people´s lives and feelings. I was willing to leave out of my dissertation the contents of the bitácoras if the community did not grant me permission to use them. The main purpose of my presence at the assembly was letting people know that I intend to use their stories in an academic endeavor, as an example of memory production ASOVIDA´s president introduced me and stated why I was there giving me the floor. I started by telling them about my own story. I mentioned my background, where I came from, and why I was so interested in the bitácoras. They listened carefully. I emphasized the academic purpose of my research and assured them that I would not use their names, that I was not going to sell their stories, and that when my research is over I would go back and show it to them. So far, I have traveled to Granada three times.

After my presentation, ASOVIDA´s president told the members of the assembly to think about my request to use their testimony. She asked them to consider why would they let me use their stories and to take their time. When the time for voting came, I was surprised and delighted with the results. The victims’ assembly approved my project and my use of the bitácoras by a vast majority. Then there were some questions and even suggestions. Granada´s victims want visibility, their voices heard, the world to know all the brutalities committed against them and their struggles for survival. Granada´s inhabitants believe that letting the world know what happened in their town can help prevent violent acts to happen again. With this in mind, they told me they granted their authorization to use their testimonies. I thanked them feeling grateful for their trust and an immense commitment to use my work to serve the people of Granada.

During this assembly the victims were asked to work in groups to think about what peace and reconciliation can be achieved in Granada (Jimena Perry, 2017)

This experience with Granada´s victims of violence changed my priorities regarding my work. I realized the enormous ethical commitment I had made in dealing with memories about a recent violent past that is still fresh, remembrances that still give people nightmares and fears. I also understood that more than the bitácoras, victims themselves are the ones who really matter. I knew this before, but seeing the people, talking to them, answering their questions raised different questions about academic research. How can one deal with intimate stories of pain without being disrespectful? How far must researcher go to achieve her or his goals? How to avoid being the kind of person that goes to a community, takes what is needed from the people, and never returns? How not to be another source of stress for the victims?

After speaking to the assembly and talking to the real protagonists of the Colombian armed conflict, I believe that analyzing the community coming to terms with its pain can encourage other social groups to do the same. In addition, I want to think that my work will inspire more victims to tell their stories and start a grieving process. I want to honor the trust Granada´s people gave me. I want my work to help them heal and I want to make the testimonies of the bitácoras known to as many audiences as possible. After attending the assembly, I feel that one of the priorities of my work should be writing a story in which the community of Granada can recognize itself. I want my dissertation to become a text in which the Granada inhabitants find their own voices. Memory production is an ongoing process that hopefully would continue until the victims feel their healing is complete, but meanwhile, their efforts for achieving peace in their town should be encouraged and acknowledged.

More by Jimena Perry on Not Even Past:

Too much Inclusion? Museo Casa de la Memoria, Medellín, Colombia

Time to Remember: Violence in Museums and Memory in Colombia, 2000-2014

History Museums: The Hall of Never Again

You may also like:

Madeleine Olson reviews Mapping the Country of Regions: The Chorographic Commission of Nineteenth-Century Colombia

Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra on Colombian history in the Netflix hit-series Narcos

Vasken Markarian traces complaint reports in the Guatemalan National Police Historical Archive

One of Taussig’s major criticisms was the key omissions he noticed in the story told by the Gold Museum. Taussig drew on his own research into the black communities located in Timibiquí in the country’s southwest. These communities were formed by black former slaves who settled in Timbiquí and began extracting gold from mines and panning it from rivers there. Despite the strong connection these communities had to gold, the museum made no mention of them.

One of Taussig’s major criticisms was the key omissions he noticed in the story told by the Gold Museum. Taussig drew on his own research into the black communities located in Timibiquí in the country’s southwest. These communities were formed by black former slaves who settled in Timbiquí and began extracting gold from mines and panning it from rivers there. Despite the strong connection these communities had to gold, the museum made no mention of them.