Lessons from London: what happens when universities place PhD students in museums?

History Museums: The Center for Memory, Peace, and Reconciliation, Bogotá, Colombia

History Museums: Museo Nacionál de Antropología, Mexico

History Museums: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

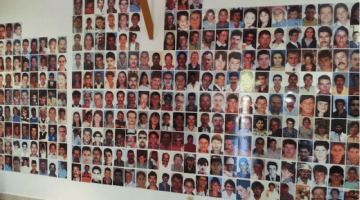

History Museums: The Hall of Never Again

The Hall of Nevermore (El Salón del Nunca Más) is located in Granada, in the highlands of Antioquia, Colombia. Granada is small place which lost 70% of its population between 1998 and 2000, going from 18,000 inhabitants to 5500 due to violence. The region saw near constant fighting among guerilla, paramilitary groups and the National Army between 1988 and the early 2000s.

History Museums: Race, Eugenics, and Immigration in New York History Museums

By Madeline Y. Hsu Ideas about race and eugenics have had a long influence on U.S. immigration and citizenship laws. A pair of historical exhibits ongoing in New York City vividly convey this troubling history. The regulations governing U.S. borders reveal the beliefs of legislators, but also many Americans, regarding what kinds of people are […]

History Museums: The Good, the Bad, and the Beautiful

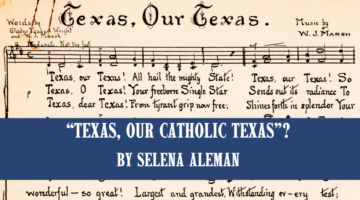

“Texas, Our Catholic Texas”?

Please join UT Libraries, Texas Catholic Historical Society, The Summerlee Foundation, LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections and The Institute of Historical Studies for: “Carlos E. Castañeda’s ‘Catholic’ Texas?” Wed & Thu, Sep. 20-21, SRH.1, Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, Second Floor Conference Room) Texans may remember singing the state song, “Texas, Our Texas,” during their state history classes in […]

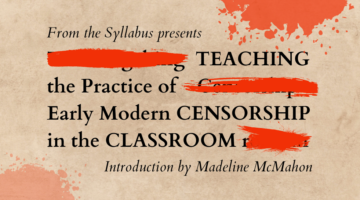

From the Syllabus: Teaching the Practice of Early Modern Censorship in the Classroom

Introduction From the editors: From the Syllabus is a new series from Not Even Past designed to spotlight thought-provoking essays, texts, and other teaching resources that generate great classroom discussions. Each installment features an introduction by a leading educator explaining on what we can learn from each featured resource. From the Syllabus will serve as […]