By Charley S. Binkow

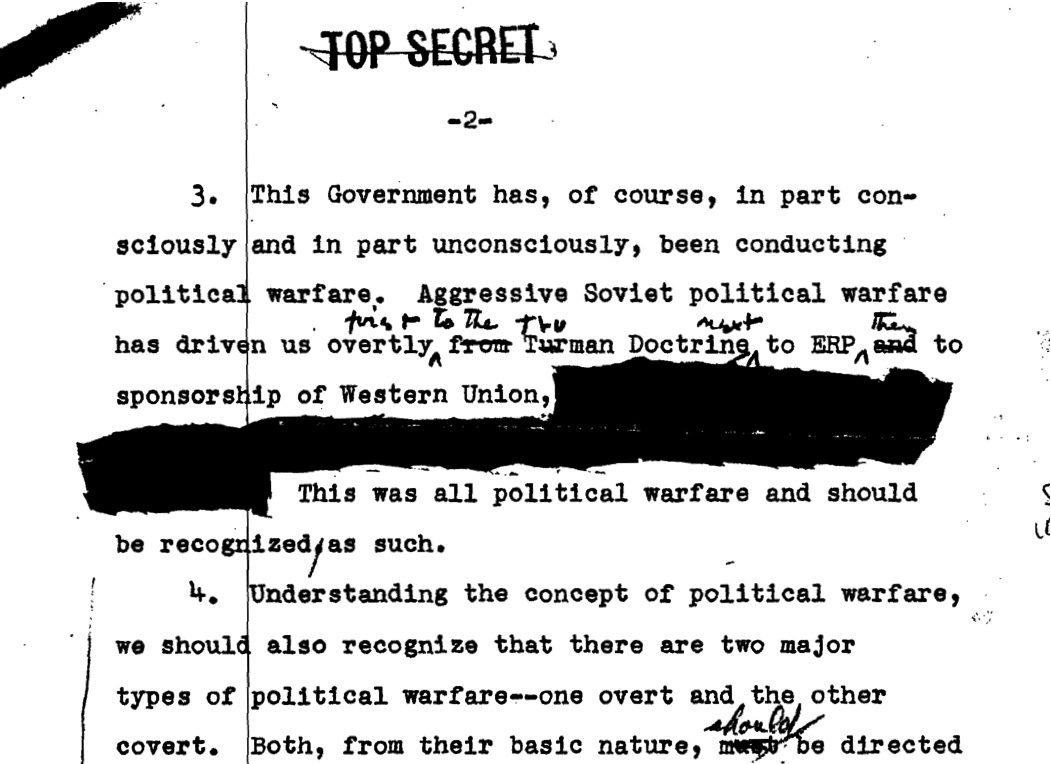

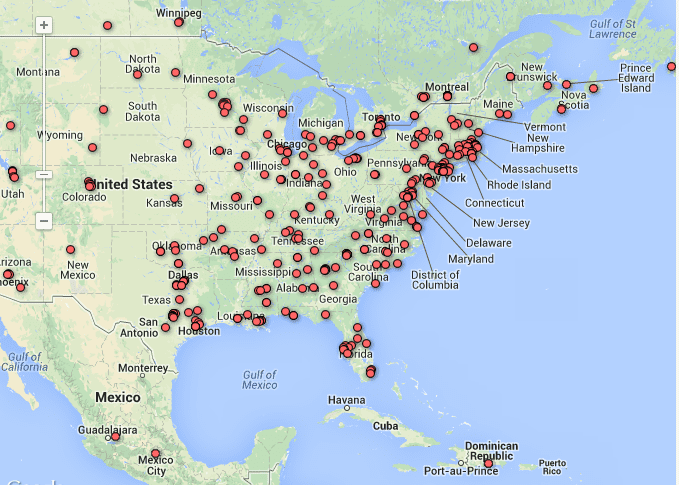

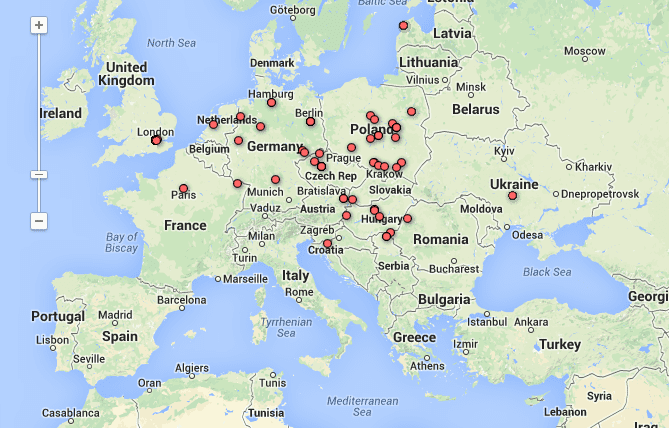

How does a nation fight a war of ideas? When the battlefield is popular opinion, how does a state arm itself? In 1949, the United States found its answer. Their weapon: the airwaves. The CIA launched Radio Free Europe in 1949 with the hopes of encouraging Eastern Europeans to defect from the Soviet bloc and weaken their countries from the inside. The Digital Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty archive gives us a declassified, thorough, and incredibly interesting view of the radio’s peak years between 1949 and 1972.

The RFE/RL collection of documents is among the many fascinating collections posted by the Wilson Center on its website: “Digital Archive: International History Declassified.” It is a treasure trove of information. Memorandums, reports, and letters, all declassified by the Central Intelligence Agency, giving us an unseen history of the station. You can see the beginnings of the program, when George Kennan (one of the architects of containment policy) stressed the need to inspire “continuing popular resistance within the countries of the Soviet World,” to its founding mission statement to “engage in efforts by radio, press and other means to keep alive among their fellow citizens in Europe the ideals of individual and national freedom.” The documents give us insight into uncertainties about the program as well. Several statesmen had doubts, like Richard Arens, who claimed RFE was harboring Marxists and broadcasting socialist propaganda. West Germany, where RFE was based, also felt a lack of control over the station and a sense of being used by the U.S.

My favorite part of the collection is its extensive collection of papers concerning the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. RFE played an important role in the uprising, at least from the Hungarians’ point of view. However, after the uprising failed, and public outcry blamed the United States and RFE for its inaction, the CIA tried its best to back peddle and “down play” the situation as much as possible. Especially fascinating are the policy reviews after the Hungarian revolution (notably its concerns with Poland and Czechoslovakia).

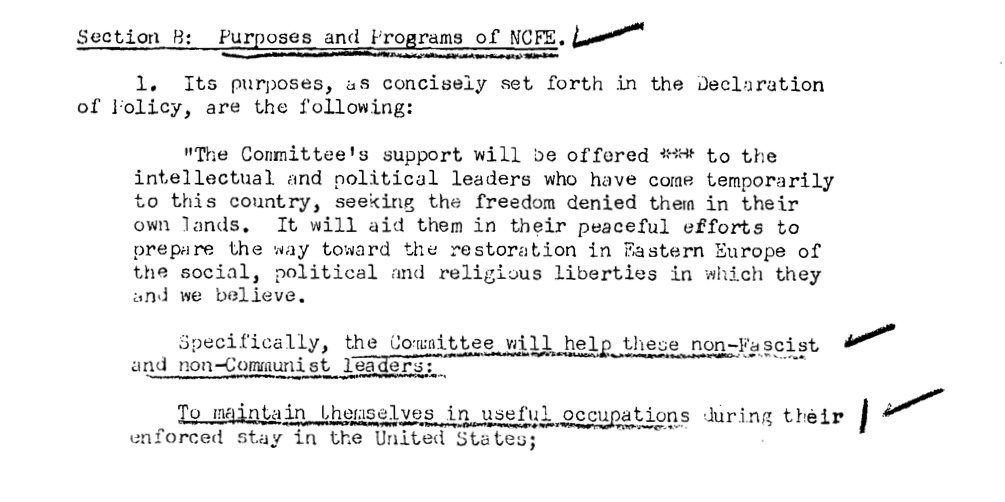

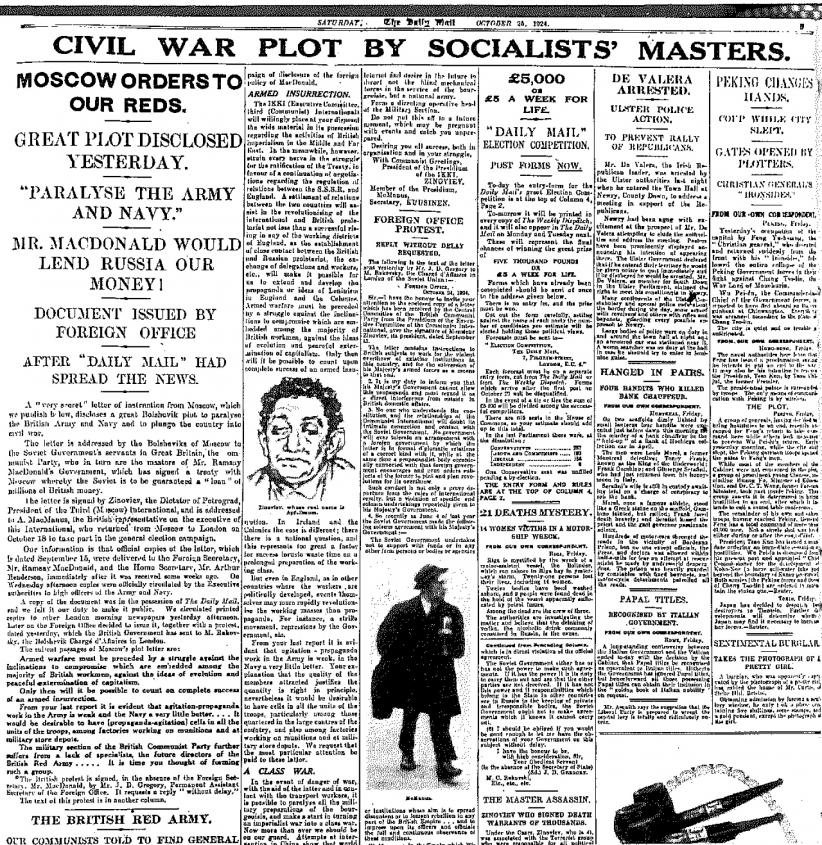

“Understanding Between Office of Policy Coordination and National Committee

for Free Europe,” October 04, 1949, a document outlining the mission of the Free Europe Committee (Wilson Center Digital Archive)

This archive is easily navigable and well worth searching. The Wilson Center also has a plethora of other digital archives, including documents on China, North Korea, Cuba, Brazil, and South Africa, as well as other archives on the Cold War in Europe and around the globe. But its collection on Radio Free Europe is an excellent place to start.

If you’re further interested in the Hungarian Revolution, you should also check out the Open Society Archives’ collection, which we featured here last week.

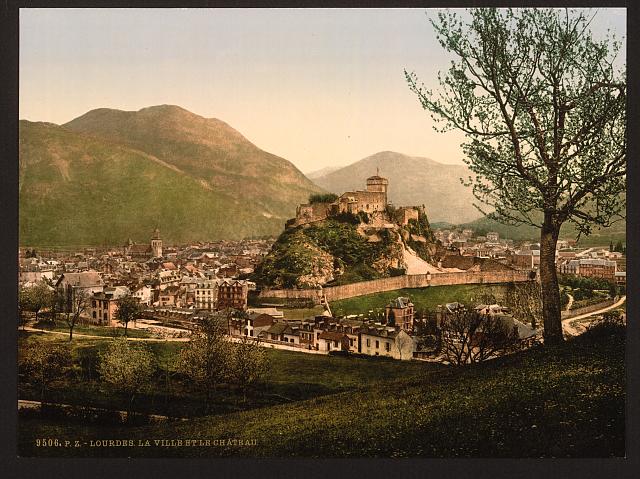

The Spanish Pyrenees, 2009 (Image courtesy of User Miguel303xm/Wikimedia Commons)

The Spanish Pyrenees, 2009 (Image courtesy of User Miguel303xm/Wikimedia Commons) The French Pyrenees, 2010 (Image courtesy of Nicolas guionnet/Wikimedia Commons)

The French Pyrenees, 2010 (Image courtesy of Nicolas guionnet/Wikimedia Commons)

by

by