The theory that dominance in society is based on a hegemonic culture was initially posited by Antonio Gramsci based on a Marxist analysis of economic and social class. Gramsci proposed that prevailing cultural norms should not be perceived as natural and inevitable but in fact represent artificial social constructs imposed by the ruling class and that the roots of these constructs reveal the instruments of social-class domination. In the framework of the nation, this translated to the state maintaining its position through a mix of sheer force (or coercion in political society) as well as the active participation of the subordinate groups (or consent through hegemony in civil society). Gramsci’s work on domination and consent founded in hegemony inspired many scholars that followed, and particularly those studying societies emerging from European imperial rule in the decades after World War II.

One of the most significant works in the field of post-colonial studies to draw on Gramsci’s concept was Ranajot Guha’s Dominance without Hegemony. Published only in 1998, the groundwork for the book had been laid almost fifteen years earlier with the establishment of the Subaltern Studies journal in 1982, which was founded by an initial group of eight South Asian scholars. The term “subaltern” is also an allusion to Gramsci, who called for the emergence of “subaltern intellectuals” to challenge the cultural hegemony of the ruling bourgeois class. In this context, subaltern refers to any person or group of inferior rank and position to those who dominated society. While the works of prominent post-colonial scholars such as Frantz Fanon and Edward Said had previously challenged the extent of hegemonic dominance in societies under direct or indirect colonial rule, the Subaltern Studies Group in its journals and in the overall approach of the individual scholars beyond this sought more directly to apply Gramsci’s theoretical relation of dominance to hegemony to the context of India and to highlight the issues with it.

One of the most significant works in the field of post-colonial studies to draw on Gramsci’s concept was Ranajot Guha’s Dominance without Hegemony. Published only in 1998, the groundwork for the book had been laid almost fifteen years earlier with the establishment of the Subaltern Studies journal in 1982, which was founded by an initial group of eight South Asian scholars. The term “subaltern” is also an allusion to Gramsci, who called for the emergence of “subaltern intellectuals” to challenge the cultural hegemony of the ruling bourgeois class. In this context, subaltern refers to any person or group of inferior rank and position to those who dominated society. While the works of prominent post-colonial scholars such as Frantz Fanon and Edward Said had previously challenged the extent of hegemonic dominance in societies under direct or indirect colonial rule, the Subaltern Studies Group in its journals and in the overall approach of the individual scholars beyond this sought more directly to apply Gramsci’s theoretical relation of dominance to hegemony to the context of India and to highlight the issues with it.

The Subaltern Studies Group’s take on dominance without hegemony in India, as outlined by Guha in his book, begins with the experience of the British Raj and the inherent difference between the colonial history and that of the metropolitan bourgeois state narrative in Europe (as well as America). In colonial India, political coercion outweighed persuasive cultural hegemony in civil society and this carried over to the post-independence period as well. The post-colonial elite (both newly minted bourgeois capitalists and more well-established land owners) had distinctly different interests than the subaltern groups in the new nation. Consequently, Guha argues, this split in the politics of the state meant that the Indian bourgeoisie, unlike the European bourgeoisie, failed to establish Gramscian cultural hegemony over Indian subalterns. The inability of the colonial state and then the independent nation to assimilate civil society into political society, as had been accomplished in the West, led the state to exercise dominance without hegemonic consent.

In the decades since the subalternists began their influential work, the theory of dominance without hegemony has not been without its critics. Most recently, Vivek Chibber challenged the conclusions reached by Guha and his colleagues Partha Chatterjee and Dipesh Chakrabarty. In particular, Chibber takes issue with the assumption by these scholars that the narrative of hegemony could be founded in the agency of the bourgeoisie, and that they in turn could speak for the nation in the West or the East. The Subaltern Studies Group, Chibber argues, romanticized the bourgeois democratic mission and capitalist power relations. Among other things, the Subalternists misdiagnosed cultural differences as the failure of the dominant classes to secure consent through hegemony – a process that Chibber asserts is more grounded in political economy than the absolute social hegemony the Subaltern Studies Group refutes. Chibber ultimately calls for a more nuanced understanding of the nature of dominance and hegemony in Europe, which he asserts the subalternists mistakenly use as a counter-factual.

Ranajit Guha, Dominance without Hegemony: History and Power in Colonial India (Harvard University Press, 1998)

Sources:

Vivek Chibber, Postcolonial Theory and the Specter of Capital (2013).

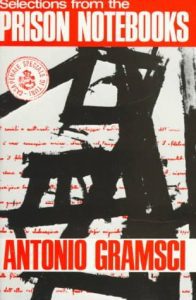

Antonio Gramsci, The Antonio Gramsci Reader, ed. David Forgacs and Eric Hobsbawm (2000).

Ranajit Guha, Dominance without Hegemony: History and Power in Colonial India (1998).

You may also like these articles in our Social Theory series:

Ben Weiss explain’s Slavoj Žižek’s theory of Violence

Jing Zhai on Jacques Derrida and Deconstruction

Charles Stewart talks about Foucault on Power, Bodies, and Discipline

Juan Carlos de Orellana discusses Gramsci on Hegemony

Michel Lee explains Louis Althusser ideas on Interpellation, and the Ideological State Apparatus