This and other articles in Primary Source: History from the Ransom Center Stacks represent an ongoing partnership between Not Even Past and the Harry Ransom Center, a world-renowned humanities research library and museum at The University of Texas at Austin. Visit the Center’s website to learn more about its collections and get involved.

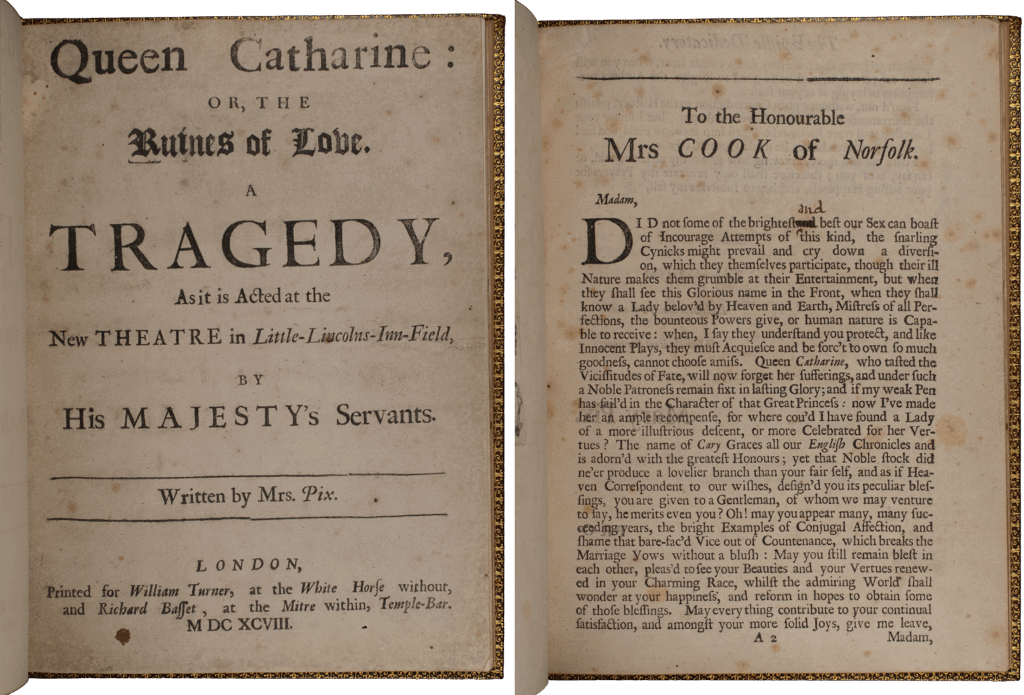

Mary Pix’s Queen Catharine; or, the Ruines of Love (1698) was not a smash hit. Very few of her plays were. While a handful enjoyed revivals on the stage throughout the 1690s and 1700s, none of her playbooks received a second run in print. That said, after Aphra Behn and Susanna Centlivre, Mary Pix was the most prolific woman playwright of the English Restoration.1 No fewer than twelve of her plays were produced between 1696 and 1706.2 And like many playwrights, regardless of gender, Pix used print to court aristocratic interest and, ideally, patronage. The copy of Queen Catharine at the Ransom Center may be the very one that Pix presented to the book’s dedicatee, Cary Coke.

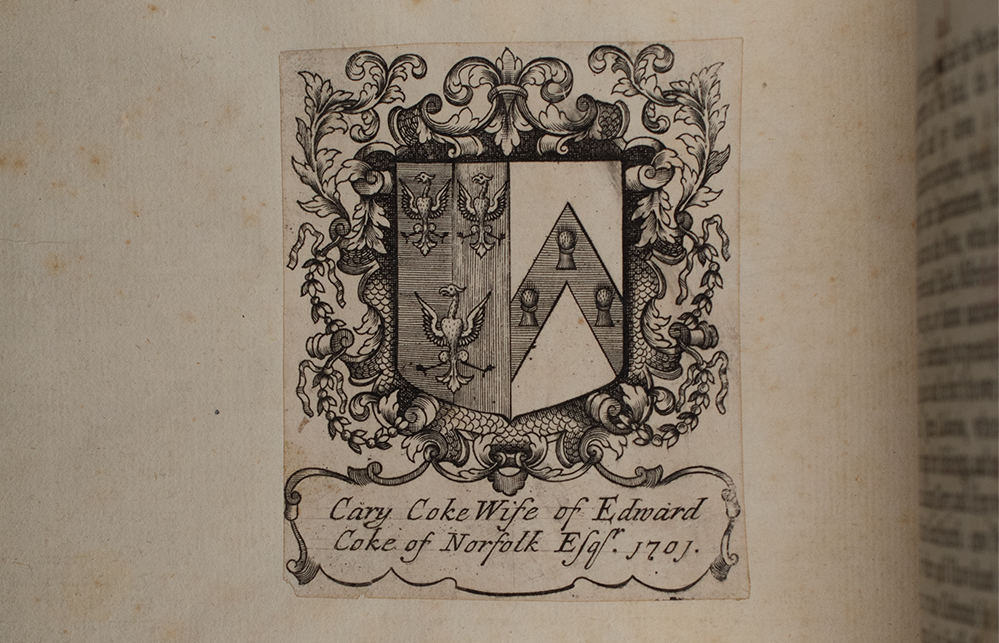

Part of the George A. Aitken Collection, which came to the Ransom Center in 1921, this copy of Queen Catharine is, from the outside, typical of the playbooks that went through the hands of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century book collectors. It has been rebound in red leather and features marbled endpapers. Oddly, though, the volume’s only bookplate before arriving at the University of Texas appears not at the very front but on a leaf inserted after the playbook’s title-page. On the back—the verso—of that leaf, the plate reads, “Cary Coke Wife of Edward Coke, Esq. 1701.” The fact that it comes after the endpapers is not in and of itself unusual: book collectors in the early eighteenth century understood, perhaps better than modern ones, the impermanence of book bindings, and often glued their plates to the blank versos of title-pages. A bookplate following a title-page, however, is odd. A little more than 300 of the Cokes’ playbooks are now at Oxford University’s Bodleian Library, and none include a plate in this position. Of the 30 total volumes in which they have been bound together, 24 include either Edward or Cary’s plate. In 22 of them, it appears on the verso the first play’s title-page.3 So, the question becomes: why is Cary Coke’s bookplate on an extra leaf in this copy of Queen Catharine? And what can this tell us about the history of this playbook before it arrived at the University of Texas?

One clue may lie in a single handwritten correction. On the first page of the dedication to Coke, there is a typesetting error. What should be “brightest and”—“Did not some of the brightest and best of our Sex can boast of incourage attempts of this kind…”—lacks a space between the two words, appearing as “brightestand.”4 In the Center’s copy of Queen Catharine, someone has attended to this error, crossing out “and” and rewriting the word above in an early hand that roughly mimics the font. Given the bookplate, the emendation may have been made by Pix herself before she presented the book to Cary Coke. Or maybe it was made by Coke upon receiving the playbook from Pix. If a presentation copy, the playbook may have been kept separate from the bound playbooks, which include another copy of the Queen Catharine edition. (The volume including that copy bears Edward Coke’s bookplate, not Cary’s.) It isn’t hard to imagine that Cary Coke would want a special, personal copy of a play dedicated to her to remain apart from the larger, household collection of plays. It also isn’t difficult to imagine Pix taking a moment to correct a typesetting error in her dedication before sending or presenting the copy to the dedicatee. Of course, though, we can probably never know for sure.

There is also the matter of Aitken himself. That a Pix play found a home in Aitken’s collection at all is appropriate, given his wide-ranging interest in English books and a scholarly interest in the literature of Queen Anne’s reign in particular.5 However, few records indicating when and from where Aitken purchased his books survive. Aitken’s association with notorious book-forger and thief Thomas J. Wise (a few examples of their personal correspondence do survive in the Aitken collection) complicates matters further. Wise’s determination to create fine copies of early playbooks for his own collection (in)famously drove him to steal leaves out of copies at the British Museum (now the British Library).6 He also went so far as to forge entire editions of nineteenth-century books that did not exist, relying on his otherwise sterling reputation as a bibliophile to pass said forgeries off as legitimate.7 Since a working connection is known to exist between Aitken and Wise, and given Aitken’s relative lack of auction records or other bills of sale, it may be necessary to approach the Aitken collection with some degree of caution. But should Aitken and, by extension, the Ransom Center’s Queen Catharine be found “guilty by association” with Wise?

Arguably no. Although the bookplate placement is curious, the playbook leaves themselves show no signs of having been manipulated by Wise or his binder. And Wise, fortunately, is not known to have forged provenance in this way. Aitken, too, clearly had many sources for his books apart from Wise. How the Cary Coke’s copy of Queen Catharine left the rest of the playbook collection at her home, Holkham Hall, is unclear, but it appears that it did in fact end up here in Austin, Texas, offering a window—even if a clouded one—into the relationship between two influential literary women.

Rachel Spencer is a PhD candidate in the Department of English at UT Austin. Her research focuses on 16th- and 17th-century drama, book history, performance studies and theater history, and feminist theory.

1 The “Restoration” is the period after 1660 when Charles returned to England as King Charles II. Having been closed since 1642, London’s theaters also reopened that year.

2 There are still some questions as to whether Pix may have produced thirteen plays, but the scholarly consensus tends to consider Zelmane no longer part of her canon. See: Annette Kramer, “Mary Pix’s Nebulous Relationship to Zelmane,” Notes and Queries 41, no. 2 (1994): 186-87.

3 Due to the condition of two volumes, Holk. d.4 and Holk. d.15, I did not personally confirm the location of the bookplates, but SOLO, the Bodleian’s library database, claims both volumes bear Edward Coke’s bookplate.

4 Harry Ransom Center, Ak P689 698q

5 “Aitken, George Atherton, 1860-1917,” The Online Books Page

6 David Foxon, Thomas Wise and the Pre-Restoration Drama: A Study in Theft and Sophistication (London, The Bibliographical Society, 1959).

7 The forgeries were first revealed in John Carter and Graham Pollard, An Enquiry into the Nature of Certain Nineteenth-Century Pamphlets (London: Constable and Company, 1934).

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.