By Ben Weiss

A recent piece in The Economist claims that, “One thing many PhD students have in common is dissatisfaction. Seven-day weeks, ten-hour days, low pay and uncertain prospects are widespread. You know you are a graduate student, goes one quip, when your office is better decorated than your home and you have a favourite flavour of instant noodle.”

When I was considering enrolling in the University of Texas History PhD program, I heard similar sentiments from peers and discovered many analogous articles. Despite the deluge of criticism I found myself wading through during application season, stubbornness and ambition persevered, and I entered the program in August of 2013. I decided to get a PhD in History as training for pursuing a career in government policy making. Many people making policy decisions lack significant contextual knowledge about their fields, which has a negative impact on overall policy effectiveness. Nearly three and a half years later and having experienced many of the drawbacks associated with grad school, I am still content with my decision.

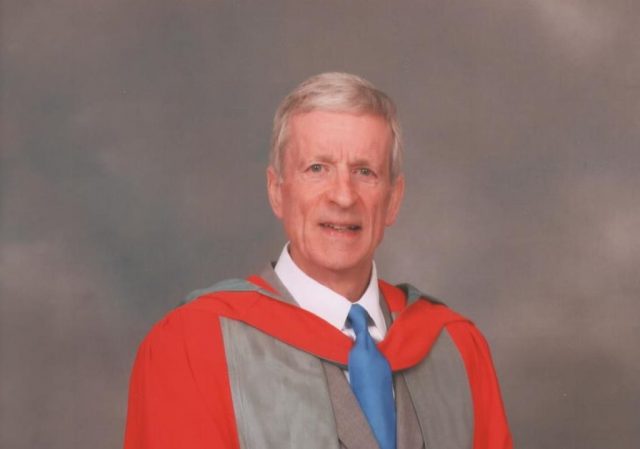

During my undergraduate years at UT, I took a course with the highly regarded historian Tony Hopkins. Though I often find myself remembering his stirring lectures and exceptional oration skills, one moment in the course especially resonated with my ambitions. One day, he mournfully stated that the last of the generation of economists who were well versed in history recently retired or passed away. His words deeply echoed my feelings about the profound lack of historical and cultural understanding among the vast majority of contemporary policymakers.

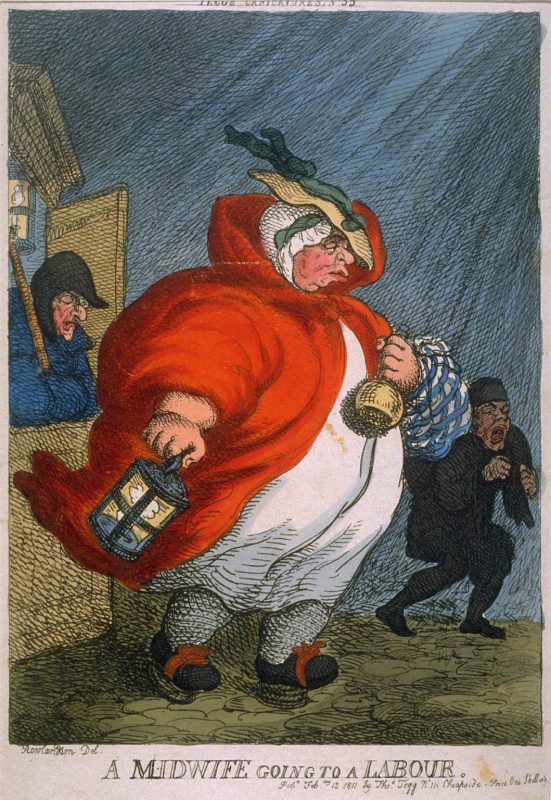

The distinguished economic historian A.G. “Tony” Hopkins taught at UT from 2002-2013 (via Wikimedia Commons).

I work on the history of sexual health politics during the colonial period in southern Africa with the goal of doing policy work for American HIV/AIDS relief efforts in the same areas. Historically, western medicine frequently has produced traumatic and violent experiences in African societies, where perspectives on sexual health and sexual education norms differ from western views and health relief campaigns have a history of becoming politicized within neo-colonial and nationalist power struggles, making American foreign health policy and its reception in Africa problematic. Many policymakers lack the historical background necessary to develop effective policy. For all the discourse on indigenous partnership that occurs as a part of American relief efforts in my focus regions, partnership occurs within the cultural and ideological framework of American public policy. For example, policymakers do not legitimately account for indigenous healing practices within their policy frameworks – either in discourse or practice – because the vast majority of policymakers fail to recognize just how much sociocultural value local medical practices hold while simultaneously overlooking the ways in which Western medicine possesses its own country specific cultural values. Americans have contributed to the tremendous progress made in fighting HIV/AIDS, but we could be doing better by integrating real historical training.

I have made this argument multiple times to potential employers as I look beyond my dissertation defense toward a career in policy making. My contentions have not fallen on deaf ears. Think tanks and other policy research institutes have indicated that my historical training really does bring valuable expertise to the table that few other candidates with other types of degrees possess.

Historical knowledge and training can inform policy from the local to the federal levels (via Wikimedia Commons).

When considering whether a PhD – and specifically one in History – is worth it, I would consider asking what such a degree can add both to one’s personal goals and to making one competitive on the professional job market. When I was thinking about graduate school, I reflected on Tony Hopkins’ words and realized that I could not, in good conscience, work in HIV/AIDS relief (something I have been passionate about for close to a decade) without acquiring the knowledge that was lacking in the field. I also believed that a PhD would enhance my employment prospects if I articulated the validity of my trajectory in the right way.

There is a tangible void in public policy and I firmly believe that history PhDs could have a critical role to play in filling that void in the coming years. To those who are skeptical of the decision to put so much time, money, and energy into a PhD education, I contend that the versatile PhD holds more weight now than at any other time in recent memory.

![]()

More by Ben Weiss on Not Even Past:

Slavoj Žižek and Violence.

The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective, by Robert C. Allen (2009).

You may also like:

Selling ourselves short? PhDs Inside the Academy and Outside of the Professoriate.

![]()

Like Smith,

Like Smith,