Pampa Unión, today, is a ghost town lost in the Atacama Desert, a mile high and halfway between the Chilean mining centers of Antofagasta and Calama. Founded over a century ago as a medical way station, it quickly became a resting place for nitrate miners on their days off, complete with all the supplies and entertainments that working men required. With two main streets and just one tree, the 2,000 stable inhabitants entertained a floating population of up to 15,000. The town was abandoned in 1954. All that is left today are the ruins of adobe walls with broken bits of signage and a cemetery.

Diego was the one with the artistic inspiration. They were humble ideas, at the beginning, but he took them seriously. He could move heaven and earth to make something out of whatever it was he had in his head.

So, he went up to the pampa with fifteen classmates and a couple of movie cameras, the best they could get their hands on. It was quite the production. For Pampa Unión. The idea was a short feature about a young man who goes there to meet his ghosts, the hidden history of his rootless family, buried in the toxic sands of an abandoned mining town.

They even had a visit from Diego’s baby sister. She couldn’t stay, of course, but she went for the day. They dressed her like a doll from the nineteenth century and they filmed her with flowers in her hand wandering around among the tombstones. It was traumatic for her, because some of the graves had been disturbed. For art’s sake. The point was that suffering ran deep in Chilean veins. We were a nation of exiles, slaves, and survivors. Or something like that. It would be disconcerting to be from a ghost town, I guess.

The boys went up there to rough it, but they also went to have a good time. The desert is enchanting. It has a magic that wakes up all your neurons. When you are from the city, the purity of color, light, and shadow connects your soul with the depths of life and death, past and present. I drove up to see them, about the fifth day of their odyssey. They said, whatever else I brought, to please bring water. They were running out.

There was a scene with a hot-air balloon. The protagonist needed to send a message, an urgent, desperate call for help. Like when someone lost at sea might send a message in a bottle, but airmail. As if everyone just had a hot-air balloon stashed in their billfold for emergencies. As if wind-born balloons ever made it to their intended addressees. The story didn’t have to be realistic, comrade, just visually pleasing.

Hot-air balloons were a thing, right about then, in the artistic community of Santiago. The dictatorship had been over for almost a decade, and even Plaza Ñuñoa had become a center for a new species of night life that posed as politically aware. Starving artists, the kind Neruda called, anarcocapitalistas, would show up with marionettes, walking on stilts or pointlessly lifting off hot-air balloons, in exchange for pocket change from passers-by, and demanding that a Ministry of Culture be created to fund the fog of marijuana smoke in which they floated. Diego got his hands on three hot-air balloons, bright red and white, and he took them up to Pampa Unión.

All three had to look the same, so that his team could film the scene three times from different angles and create the illusion of just one balloon. And they had to film at dawn, because that was the only time of day that the wind wouldn’t abduct their temperamental prop and send it tumbling sideways across the desert. There were about fifteen minutes of quiet just as the sun came up. After that, the wind began to swirl around like the noxious gas on the surface of Jupiter until the sun went down.

It was the first time that all fifteen of them had ever gotten up that early. Some had hardly slept. To buffer the dopamine, they drank at night. Not a good idea, not in that climate. Alcohol dehydrates you. But it was tradition. Sebastián, nicknamed el Perro, would crawl out of his sleeping bag, muttering, If I’ve said it once, I’ve said it a thousand times. I will never drink again. It was like the folksong from Carnaval in Bolivia, the one that says, they were nice boys, but they just couldn’t stop drinking.

The scene with the hot-air balloons was a success. They spent the rest of the day in the cemetery, where they got to know the whole town: names, nationalities, dates of birth and death. People died young. There were cemetery ghettos of Croatians, English, Mapuche, and even Chinese. I brought their dirty clothes home to wash. Imagine, fifteen twenty-year-olds, no showers, drinking at night and filming in the cemetery during the day. They reeked of sand, sweat, alcohol, and cadaver.

José and his brother, Francisco, went with me. They weren’t from Santiago. They were from Antofagasta. Well, they weren’t from Antofagasta, either, comrade. Their father and grandfather had grown up on the pampa. They were desert people from way back.

Walking around in the ruins, it was easy to figure out which was the street with the hardware stores, and which one had been for cantinas and bordellos. Most of the roofs had fallen in, but there were still signs painted on the walls of the once-thriving businesses. And there was junk on the ground. Kitchen middens of the future, an archeologist’s dream that we were disturbing. There were spoons and saucers, most of them bent or broken. There were wine bottles, shattered with the cork still in. There were tin plates, costume jewels, bits of clothing and other residue of a forgotten humanity from almost a century ago.

Among all the junk, we found some bent pieces of tin, one shaped into a star, another that looked like a ship, and one that was shaped like a child. The boys from Santiago, smart as they were, had no explanation. José picked one up, as if to examine it in the light, the very bright desert light, and he said, this is a toy. My grandfather used to make these. A loaded silence of amazement descended over the boys from Santiago. José had given himself away. He had revealed his roots and the endless desert sand into which they sank, publicly claiming the pampa as his own. For him, this was no short feature film. For him, la pampa was the real thing.

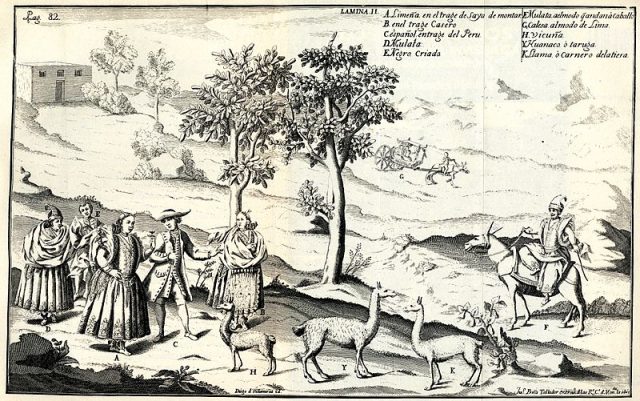

Though the original population in Pampa Unión had been inordinately skewed toward masculinity, there were females. Children were born. Sometimes, they survived the diarrhea and the diphtheria. They got old enough to need something to play with.

Supplies came up from down below. There was wine and aguardiente. There was beef, kept on the hoof, as there was no refrigeration. There were satin dresses for the prostitutes and Victrola Talking Machines to create a romantic ambiance for fantasy love affairs. But it never occurred to anyone to send up a doll, a stuffed bear, or a toy truck.

So, grandparents would take their tin shears—they had those—and try to make something nice to stimulate the imagination of the toddlers who had never known anything other than the infinite horizon, the blinding clarity of midday and the starlit dark of night. In la pampa, grandparents were often no older than about thirty-five. Anyone who lived to be forty got the hell out of there.

In Antofagasta, José’s grandfather kept making toys out of empty tin cans. A long time ago, few toys made it there, either. No toys, no fruit and no conjugated verbs. People with money took trips to Santiago if they wanted something nice. Poor children did without. Raising children was not the objective, there. You had to get the ore out of the ground. You had to get it down the mountain, onto ships, into trains and out of there. That was all. Playful little brats were slag, byproducts of some miner’s love affair on his day off.

Even so, grandfathers found tender spots for toddlers and got busy with their tin shears. Compared to X–boxes, the tin-can toys might have seemed like nothing at all. But, compared to nothing at all, comrade, well, that was another story. They were the first thing that delighted the eye of virgin innocence. For the semi-abandoned babies of the desert, tiny tin toys were shining treasures, an opportunity to imagine the garbage dump where they lived transformed into burgeoning beauty. They were a chance, maybe their only chance, to ever contemplate the world as it might have once been, as it could someday become. Those toys did tend to have sharp edges and pointy places. They were dangerous toys that prepared children for life in the Norte Grande, a life with lots of rough edges.

The guys from Santiago grew quiet. José’s revelation gave them pause. They realized the deficiencies of their own elitist upbringing. José became silent, too. He understood, in that moment, the cultural and geographical abyss that separated him from the sons of wealth, privilege, and power. He had played with those toys. Francisco had, too.

More From Nathan Stone:

Three-year-olds on the world stage

Underground Santiago: Sweet Waters Grown Salty

For further reading, see Hernán Rivera Letelier’s novel about Pampa Unión, Fatamorgana de amor con banda de música. (Santiago: Planeta, 1998)