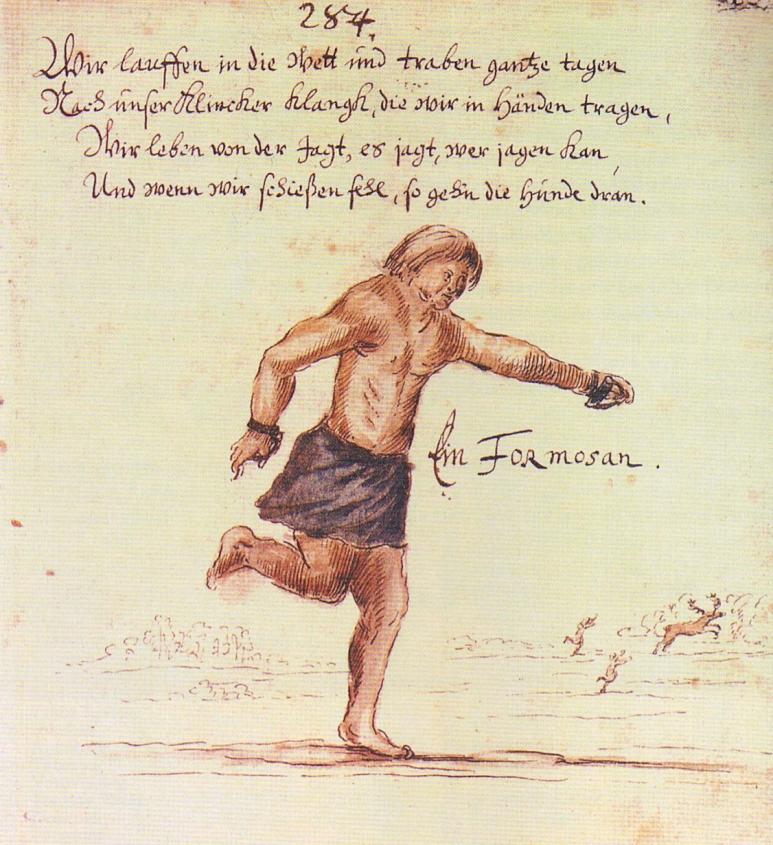

Focusing on seventeenth-century Taiwan, the island east of mainland China populated by aborigines who specialized in deer hunting, Tonio Andrade seeks to explore the theme of early modern colonization in a much larger context as part of his greater effort of analyzing global history. According to Andrade, Taiwan, neighboring China, Japan, the Philippines (controlled by Spain), was part of a colonial trade network and soon a focus of contention between the Dutch, the Spanish, the Portuguese, the Japanese and the Chinese.

Employing a variety of sources including travel and missionary accounts from Europeans, official records and correspondence from the Dutch East India Company (VOC), and documents from the Chinese, Andrade discusses the early modern colonization of Taiwan, known as Ilha Hermosa by the Portuguese, La Isla Hermosa by the Spanish, or Formosa by the Dutch. Spain strategically established a colony in northern Taiwan while the Dutch established theirs in the south in the first quarter of the seventeenth century.

1640 Dutch map of “Formosa,” the colonial term for Taiwan (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

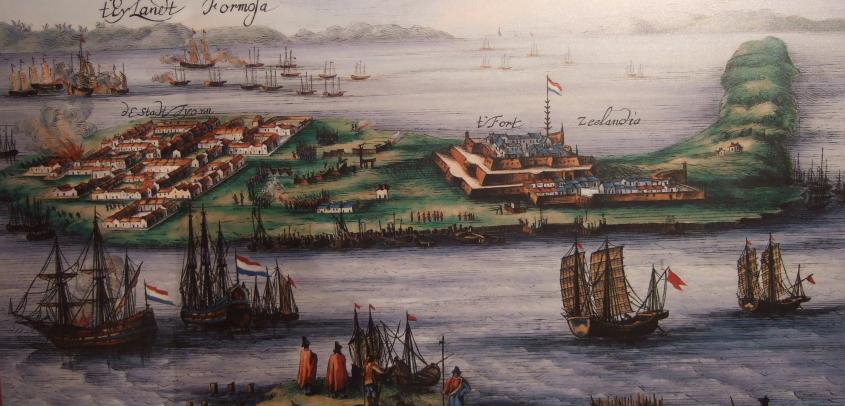

Fort Zeelandia, the Dutch East India Company’s Taiwanese headquarters (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

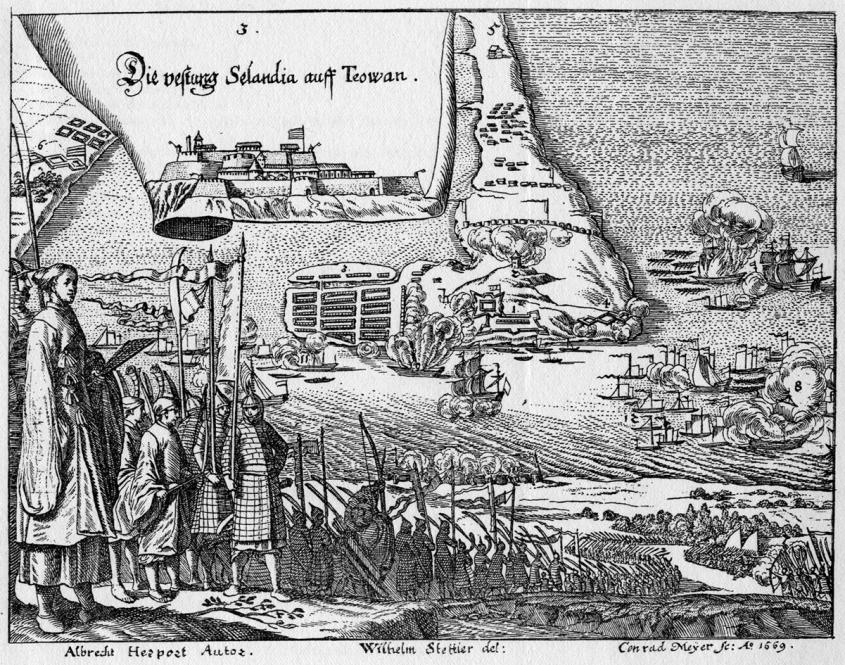

After Spain’s decreasing interest in Taiwan and their defeat by the Dutch gave it control of the island, the VOC corrected the Spanish mistake of not making their colony self-sufficient by developing an interesting strategy which Andrade calls “co-colonization”. Having determined that it would be too costly to send Dutch to Taiwan, the VOC introduced various incentives including free land, tax exemptions and property rights to attract Chinese from the nearby Fujian province in China to immigrate to Taiwan. The plantation of sugar and rice soon became lucrative business not only for the immigrants but also the VOC. In the process, the VOC also developed a lord-vassal relationship with the aborigines and gained control over the native population. Andrade argues that this co-colonization strategy was a key difference between the Spanish and the Dutch in their colonization efforts in Taiwan. This period of co-colonization between the Dutch and the Chinese was successful so long as the interests of both parties were met. Towards the end of the century, however, the VOC’s tax increase lost the support of the Chinese immigrants, ultimately leading to rebellions from many Chinese settlers and to the Dutch defeat by Zheng Chenggong, the Ming loyalist of great military power.

Dutch sketch of a native “Formosan” circa 1650 (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

1661 Dutch engraving of Chinese soldiers in Taiwan (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Andrade’s study of the colonization of Taiwan demonstrates the connections between Europe and Asia, which helps to illustrate a larger picture of early modern colonization beyond the Atlantic world. The multiple European and Asian colonizing powers in Taiwan also highlighted the intricate network of colonization in terms of not only military power but also trading relations and migration patterns. Interestingly, Andrade does not include any maps or other supplementary illustrations in the original/English version of his work, but he does so in the Chinese translation. Even more thought-provoking is the book title of the Chinese version. Instead of How Taiwan Became Chinese, the Chinese title is How Formosa Became Taiwan Prefecture, carrying a much more Sinocentric undertone. Nonetheless, Andrade’s book is a fascinating study on early modern global relations.

The Spanish Pyrenees, 2009 (Image courtesy of User Miguel303xm/Wikimedia Commons)

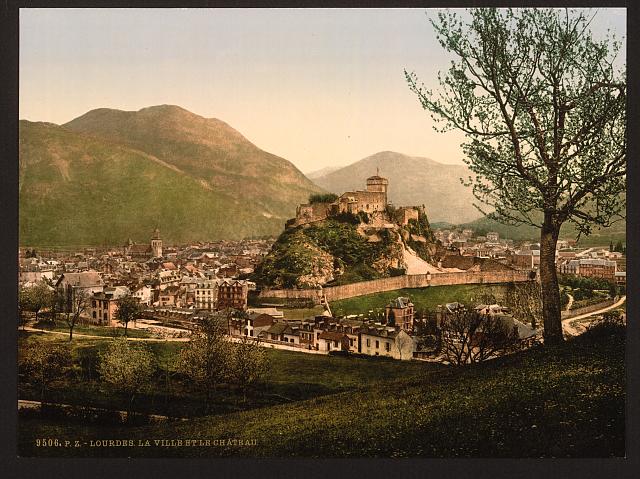

The Spanish Pyrenees, 2009 (Image courtesy of User Miguel303xm/Wikimedia Commons) The French Pyrenees, 2010 (Image courtesy of Nicolas guionnet/Wikimedia Commons)

The French Pyrenees, 2010 (Image courtesy of Nicolas guionnet/Wikimedia Commons)