by Amber Abbas

Professor Irfan Habib is probably the best-known professor in Aligarh. Born in 1931, he was a young student in the Intermediate classes during the 1940s. His father, Mohammad Habib, a staunch nationalist was the leader of the progressive factions at Aligarh. Irfan Habib is an Emeritus Professor of the Department of History but he still appears daily in the department where he sits in the office of Professor Shireen Moosvi and interacts with all of the students, other professors, Communist party activists and others who move in and out of the office throughout the day. Irfan Habib always provides hospitality to these guests: endless cups of tea and biscuits. On many occasions I had the opportunity to sit in the office and transcribe stories he would share in English or in Urdu with the people who came and went. It was some time before I could convince him to sit down with me for a formal interview about his experiences during the 1930s and 1940s in Aligarh. He was very skeptical of the methodology of my research, being as he is, a historian of medieval India and deeply invested in the investigation of documentary sources. Interviews, he reminded me, would only catch a person’s “bias,” and not “The Truth.”

In this interview, he describes the atmosphere in AMU in the years following partition and his experiences around Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination. He first emphasizes the fact that though partition caused terrible disruption at the university, with thousands of students and many faculty departing for Pakistan, the university worked to minimize its effect on students’ lives. He repeatedly told me that no class was ever cancelled, even if a professor left, another instructor stepped in to cover his responsibilities. Continuity is important as a way to show that there were Muslims at the university who worked to support independent India—contrary to the narrative that has plagued the university since the 1947 partition by suggesting that its students and professors were, without exception, traitors and fifth columnists. Habib wears his nationalism on his sleeve, even if, as a Leftist, he has not really represented its mainstream.

In this interview, he describes the atmosphere in AMU in the years following partition and his experiences around Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination. He first emphasizes the fact that though partition caused terrible disruption at the university, with thousands of students and many faculty departing for Pakistan, the university worked to minimize its effect on students’ lives. He repeatedly told me that no class was ever cancelled, even if a professor left, another instructor stepped in to cover his responsibilities. Continuity is important as a way to show that there were Muslims at the university who worked to support independent India—contrary to the narrative that has plagued the university since the 1947 partition by suggesting that its students and professors were, without exception, traitors and fifth columnists. Habib wears his nationalism on his sleeve, even if, as a Leftist, he has not really represented its mainstream.

Habib’s family had a long history of nationalist allegiance and his mother’s family had been close to Gandhi since the early years of his leadership. Habib earlier told me that Gandhi “was an idol… in our home. My mother called him ‘Bapu’ because of the family relationship, but I never heard my father referring to Gandhi as anything except ‘Mahatmaji.’ He wouldn’t even say ‘Gandhiji.’” In describing the events of Gandhi’s death, Professor Habib, however, does not emphasize his family’s grief, but the efforts of students publicly to show their solidarity with the nation. Because of the immediate suspicions that a Muslim may have committed the murder, and the anxiety that threatened the Muslims more broadly in the wake of partition, AMU stood out as a particularly sensitive site. Professor Mohammad Habib led the students from the University to the city of Aligarh, which involved crossing the railway line, the traditional boundary between the University and the majority Hindu city adjoining it. Crossing this boundary is a symbolic act of solidarity, and the Muslim students demonstrated their Indian-ness by publicly engaging in the response to Gandhi’s death. Habib also points out that many “Pakistanis”—by which he means those students whose family homes were in territories that became Pakistan in 1947: Punjab, Northwest Frontier Province, Sindh, Balochistan and Bengal—also participated in the march. Thus, even though Gandhi had been a controversial figure at the University, all students: Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, and even Pakistanis came together to mourn for the man who had risked his life in 1947 to stop the murder of Muslims in Bengal.

In conclusion he notes that the refugees—sharnyartis—who arrived at the university in 1947 and 1948 were welcomed with open arms, students gathered clothes for them, and “no incident” ever took place between Muslim students and refugees. This is important at Aligarh in particular because of its much-vaunted history of religious tolerance. Aligarh University had always considered itself aloof from “communal” concerns, but partition was a test of this culture. During the 1940s, even as the Muslim League mobilized students to support a Muslim homeland, no communal violence took place there. Political and national groups with differing perspectives put them aside to join in solidarity to support the university and the state in 1947 and 1948—and this is a very different kind of story from that we hear in Punjab, in Delhi, in places where violence and not peace characterized this time.

LISTEN TO THE ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW HERE

READ THE ORAL HISTORY TRANSCRIPT HERE

Photo Credits:

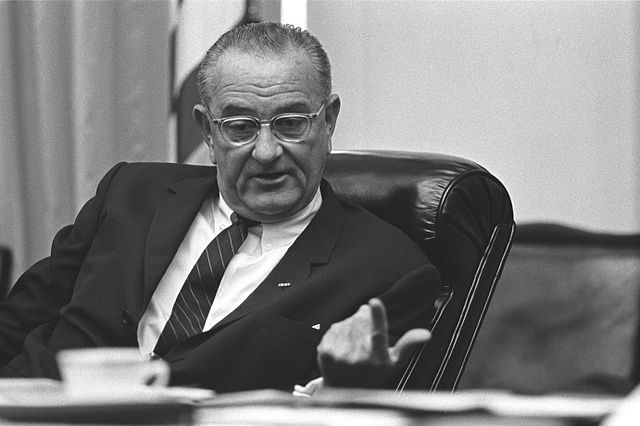

Amber Abbas, untitled portrait of Professor Irfan Habib

Author’s own via Not Even Past

Yann, Gandhi During the Salt March, March 1930

Author’s own via Wikimedia Commons

Syed Gibran, Aligarh Muslim University

Author’s own via Wikimedia Commons

You may also like:

Voices of India’s Partition, Part II: Interview with Mr. S.M. Mehdi

Voices of India’s Partition, Part I: Interview with Mrs. Zahra Haider

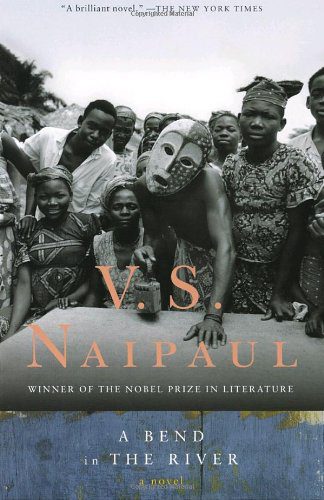

Much like its eponymous waterway, V.S. Naipaul’s A Bend in the River meanders steadily through the dark reality of postcolonial Africa, alternately depicting minimalist beauty and frightening tension. Like Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, subtle prose reveals the timelessness of the continent’s remote corners alongside human corruptibility. Yet, Naipaul moves his narrative closer in time to contemporary Africa, demonstrating that the horrifying legacies of colonialism did not end with Europe’s retreat. In A Bend in the River, the struggle to establish national identities in the wake of Western imperialism takes center stage, with “black men assuming the lies of white men” in order to govern.

Much like its eponymous waterway, V.S. Naipaul’s A Bend in the River meanders steadily through the dark reality of postcolonial Africa, alternately depicting minimalist beauty and frightening tension. Like Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, subtle prose reveals the timelessness of the continent’s remote corners alongside human corruptibility. Yet, Naipaul moves his narrative closer in time to contemporary Africa, demonstrating that the horrifying legacies of colonialism did not end with Europe’s retreat. In A Bend in the River, the struggle to establish national identities in the wake of Western imperialism takes center stage, with “black men assuming the lies of white men” in order to govern.

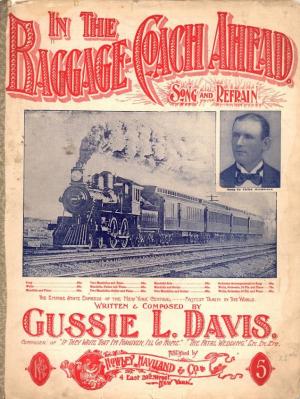

The song was the most popular composition of

The song was the most popular composition of  In 1925, he re-imagined himself as a hillbilly singer and achieved his greatest popularity with

In 1925, he re-imagined himself as a hillbilly singer and achieved his greatest popularity with