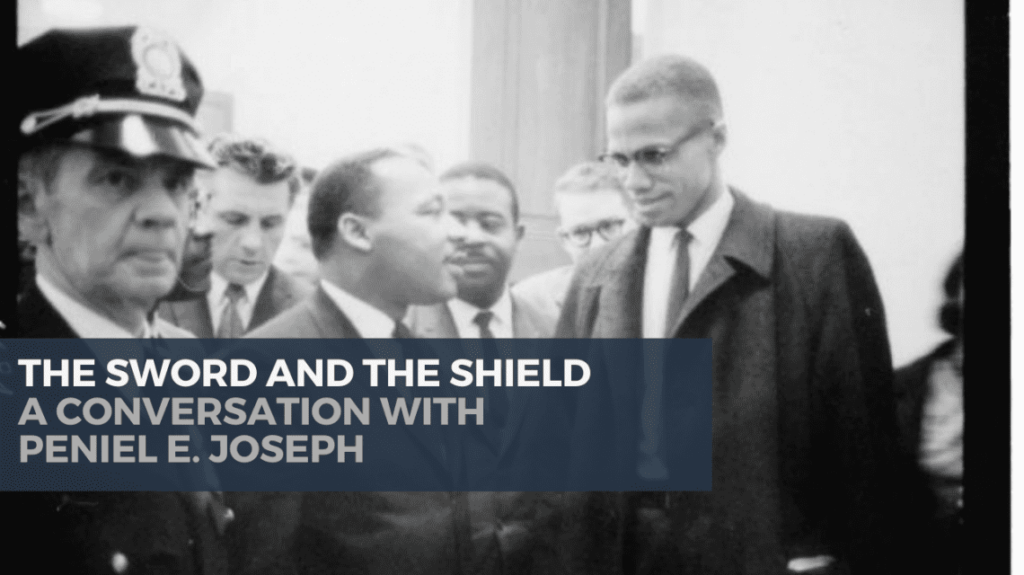

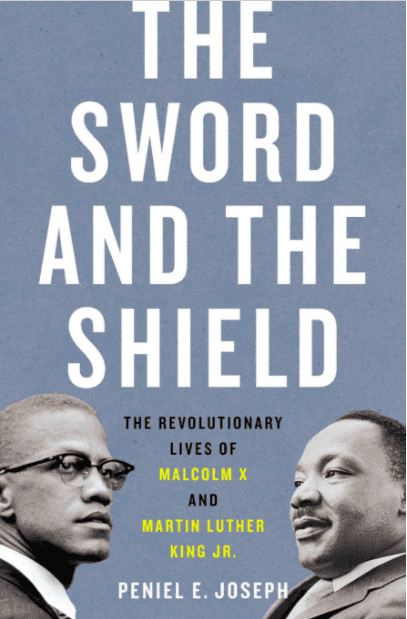

In this conversation, Dr. Peniel Joseph discusses his new book, The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. This dual biography of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King upends longstanding preconceptions to transform our understanding of the twentieth century’s most iconic African American leaders. This is part II of the conversation. Part I can be seen here. The Not Even Past Conversations Series was born out of the extraordinary circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic. It takes the form of an interview held informally (usually at home) over Zoom with leading scholars and teachers at the University of Texas at Austin and beyond. The following is a lightly edited transcript of a conversation between Adam Clulow and Peniel Joseph.

AC: You talk about the suffocating mythology that sometimes surrounds Dr King and Malcolm X. One of the parts of your book that’s so striking is your discussion of the ‘I Have a Dream’ speech. Can you talk about this moment and that speech?

Is that the case immediately? The speech has a huge impact and it’s very widely publicized and reported but I get the sense that very quickly people are focusing in on those parts that we all know and the rest of the speech is elided. Is that the case, that this understanding comes into being very quickly? Or is there a moment when the speech as a whole is considered?

PJ: I think the speech gets a Janus-faced treatment. The Black press treats it in a very holistic way. The white press is going to focus on ‘I Have a Dream’. John F. Kennedy says ‘I Have a Dream’ as soon as he meets King. It’s important to remember that the Black press, the Chicago Defender, the Pittsburgh Courier the New York Amsterdam News, Los Angeles Herald Dispatch, this is how most of the 16, 17, 18 million Black people got their news. You know, Black people were rarely written about in say The New York Times. King is an exception. Most of the time Black people were written about in major newspapers was for having committed some kind of crime. So the Black press really gets what he’s trying to say. And even the march on Washington, the Black press gives it its full title. It’s the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. So that economic aspect is really there for the Black press. But I would say that the mythologizing starts, yes, early and often when we think about the mainstream.

AC: So you talk about this kind of “children’s bedtime story” version of Civil Rights that is sometimes told. And it’s often told as a singularly American story. What really struck me in the book is the global dimensions of this story. You talk about Dr King and Malcolm X bestriding the global age of decolonization. They meet with Ben Bellah, the first President of Algeria and both travel across the world. Malcolm X travels repeatedly and is welcomed, you say, as America’s Black Prime Minister. So is Dr King. Can you say more about these figures as global icons in a much wider process of decolonization?

PJ: Yes, definitely. They’re both hugely impacted by this global age of decolonization. There’s been great work on Black internationalism done by Penny Von Eschen and Brenda Gayle Plummer and Thomas Borstelmann, Mary Dudziak, and Gerald Horne, whose whole career has focused on Black Internationalism with dozens of books. When we think about Malcolm and Martin, both of them are global figures. They converge at the intersection of anticolonialism and human rights, both of them.

Malcolm, I would argue, is even more interested in the global stage because in a lot of ways he’s able to get more global support than he is domestically. I think King is interested in the global stage but as his domestic reputation swells, he really utilizes global support to impact the domestic struggle. Whereas Malcolm is really trying to utilize the world stage to push for anti-racism and the defeat of white supremacy in, for example, the United Nations, and also to have coalitions in the Organization of African Unity that will censor the United States for its mistreatment of African-Americans. In a very specific, granular way they both in the 1950s take trips overseas. So King goes to Ghana in 1957 and is able to witness Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah. When we think about Nkrumah he is such an important figure. He’s really the post-war avatar of Pan Africanism as a nation state building project on the continent of Africa. He makes mistakes. But symbolically, he is this unbelievably important figure. Malcolm X meets him in Harlem. Martin meets him in Ghana. Malcolm later meets him in Ghana.

So King gets to Africa first. In 1957. King spends a month in India in 1959. The India trip is crucial. King’s India trip and seeing all that poverty and the caste system in India makes King understand that he has been put on Earth not just to defeat racism and white supremacy, but actually to defeat poverty globally. These are massive ambitions that most humans will never have, He really believes it. That’s what’s so extraordinary and exciting about studying these figures. Malcolm visits the Middle East in 1959, spends five weeks there, visits Saudi Arabia, visits Khartoum, Egypt, all these different places. He meets up with Anwar El Sadat, the vice president of Egypt, the future president, Egypt.

Malcolm starts making critical alliances with Middle Eastern and African diplomats in the 1950s. Malcolm had such good alliances, that one of the little known facts I talk about in the book, is that Malcolm X has an office at the United Nations. He’s got it through the connections with African and Middle Eastern diplomats. So Malcolm goes in and out of the UN all the time with a briefcase. And he’s an extraordinary figure in this sense.

So as the 60s progressed, you see Dr. King with Ben Bella. King becomes this figure for anticolonial activists who especially are interested in human rights, but especially interested in also pressuring the United States to recognize their activism as something that’s good and virtuous, even as the United States has this ultimate contradiction of not just Jim Crow segregation, but really utilizing state violence against Black people.

In 1964, Malcolm goes overseas for about 25 weeks. He goes to the Hajj pilgrimage in Mecca. He goes to Nigeria. He goes to Tanzania. He goes to Ghana. Malcolm is in Ethiopia. He’s in Cairo. He’s in London. And Birmingham. And Smethwick. And Oxford. He’s in Paris. So what Malcolm is trying to do is, one, he really becomes a statesman who is giving the global audience, the world audience, a firsthand account of his experiences as a Black man and as a Black person in America.

He’s telling Africans about the depth and breadth of racism and white supremacy. He’s repudiating the State Department’s notion that things are getting better. Malcolm is actually even harsher globally than King is. By 1964 when King travels overseas, he travels to Scandinavia to accept the Nobel Peace Prize. So in a way, King is always giving, until he’s coming out against the Vietnam War, etc, he’s giving a more optimistic vision.

Malcolm finds some optimism in the fact that anticolonialism has worked and he wants help. Malcolm meet with Fidel Castro in Harlem September of 1960, and he’s telling Fidel that your struggle is our struggle and our struggle is your struggle. Malcolm is telling that to Kwame Nkrumah, Julius Nyerere in Tanzania. What’s so interesting about Malcolm is that so many African revolutionaries respect Malcolm. He is willing to speak truth to power. So the global component is really important for both of them. I would say that Malcolm really tries to cultivate that global component even more than King. And I think it’s out of necessity.

But it’s also because Malcolm is this revolutionary Pan Africanist and also a global Islamic figure. You know, I make an argument that he’s always Muslim, both within the Nation of Islam and then when he becomes an Orthodox Muslim. So just because he’s in a different sect doesn’t mean that he doesn’t believe he’s a Muslim.

They are secular, but these are two faith leaders. They bring this real morality to what they’re doing. And it’s not a cheap morality that we have in our society today about who’s sleeping with whom. It’s the morality of: does human life matter? Should we protect children? Should we protect communities? Should we not torture people? At any time? Any place? Should we be, and this is where King’s very important here, a society that is nonviolent but we are not morally equivocating about that nonviolence.

King believes in nonviolence. Whether it’s white sheriffs who are attacking Black people or it is people in Vietnam who are considered the enemy. The United States is dropping napalm. And again, these are crimes. These are crimes against humanity that the United States is committing. No matter what we do, we can never take back these acts. Right. And so King is saying that, right. And that’s when King, I argue, April 4th, 1967 becomes a revolutionary because there’s no turning back after that. There’s no handshakes with President Johnson and President Johnson doesn’t come to his funeral.

AC: Malcolm X and Dr King exist in a global moment of decolonization. Do you see a parallel between that moment and what’s happening now with Black Lives Matter? Because one thing that’s been so striking is the way these protests have gone global in a way that could not have been predicted two years ago. Do you see parallels between the years you discuss in the book and the global Dimensions of Black Lives Matter which have has swept across the world in unprecedented and unpredictable ways and galvanized people in many different countries?

PJ: Absolutely. I think there’s parallels and I think we’re at another crossroads. I think the parallels are, again, also between the global north and the global south, because as we’ve seen, the underdevelopment of the global south and really the exploitation of the global south has continued with a different kind of colonization. And that colonization is a kind of economic colonization. Right. Because of these unfair distributions of wealth created by globalization. Globalization, that in and of itself is not a bad thing, just like gentrification. But we have made sure that the distributions or the supply chains of power and privilege versus the supply chains of misery and greed are distributed along racial and economic lines, ethnicity lines, different lines based on identity and geography.

So in a way, even as indigenous groups got rights of political self-determination – probably our biggest global example after King and Malcolm’s time is going to be Nelson Mandela in South Africa. Yes, the ANC absolutely got political power in South Africa, but without connected economic justice and equality. The segregation, the economic impoverishment has actually increased even though now we have Black billionaires and African billionaires in South Africa, too. So the whole world is absolutely in the throes of a rebellion against this inequality that is organized around anti-black racism, but it’s organized around intersectional injustice based on your race, class, gender, sexuality, how you identify.

So we’re seeing this. And I think that King and Malcolm actually anticipated this crisis, and that’s why they were interested in thinking of human and civil rights as a Human Rights movement, this bigger movement that was going to guarantee redistribution of wealth and guarantee citizenship for, yes, Black people, but for all people.

AC: We’re going to return to Dr King in a second but you can say more about how Malcolm X changes and evolves? He’s often presented in a very limited way that does not encompass the complexity of the individual, but also just how much he changed across this period. Although you cover their whole lives, the book really focuses on a relatively compressed space of time and he travels a remarkable road in this period.

So let’s talk about the last two chapters of the book, the Radical King and the Revolutionary King. And so we talked about the ‘I Have a Dream’ speech. Let’s talk about the Riverside speech, in 1967. This is an extraordinary speech that is very different from popular understandings of Dr. King. It’s stunning in its repudiation of US involvement in Vietnam. You write in the last years of his life that Dr King was transformed “into a revolutionary dissident vilified in quarters that once feted him.” Do you think he anticipated the strength of this backlash?

PJ: I would say he didn’t anticipate how big the backlash would be because I think that he thought what would protect him was the mainstream accolades that he had gotten before. So he was a Nobel Prize winner, was somebody who had been a leader of a social movement, who was on par with Presidents of the United States. And people knew that King was a serious, sober person politically. He wasn’t prone to making wild eyed statements. And when you read the speech, the speech is very sober. I mean, it’s very critical. But it’s not even his most critical speech against the war. That’s going to start really at the end of that month, because he’s going to do a speech on April 4th, April 15th. He’s at the spring mobilization, which is the largest anti-war demonstration up until that time. 400,000. Two years later is going to be marching with over a million. That’s in Central Park with Benjamin Spock. Harry Belafonte.

But then April 30th is when he does the speech at Ebenezer Baptist Church, where Stokely Carmichael is in the front row. He says he’s not going to study war no more. It’s a much more stinging indictment. And Stokely leads the standing ovation for that speech. So the Riverside speech, I mean, I think one of the things he talks about when he says America is the greatest purveyor of violence in the world is very, very important, because I think that speech is very similar to what Malcolm X is saying when he says the chickens have come home to roost.

And one of the things that King starts to channel, I argue in the book after Malcolm’s assassination, is really Malcolm’s framing of structural racism and white supremacy and imperialism and racial violence and this idea that the United States being a deployer of that kind of violence is always going to have some kind of karmic payback. For Malcolm, he was talking about the Kennedy assassination, for King the reason why he breaks with Lyndon Johnson. He’s saying, look: we’re immorally killing all these people in Vietnam, and the Great Society is failing now. In a television interview in 1966, he says, your money goes where your heart goes. And the president’s heart and the country’s heart is in Vietnam. And he was right. I mean, all that money, we know retrospectively, we should have poured that into urban cities and poured that into rural areas and anti-poverty and employment and guaranteed basic income. We could have given everybody health care and income and not murdered all those people. So, again, what’s interesting about King is he takes that weight on for himself. So he feels the weight of the US’s morally reprehensible actions in a way, I think that elected leaders should because that would prevent you from doing it. So King feels that enormous psychic weight.

And he feels that about poverty. He feels that about violence. And so he becomes this very clarifying figure. But he starts to use nonviolence as a political sword in the way that Malcolm X had talked about. And King starts speaking truth to power, saying Congress, the halls of Congress are running wild with racism. In 1967 before the American Psychological Association, he’s saying the roots of urban rebellions are white supremacy, and white racism is producing chaos. And the media says that there would be peace if Black people stopped rebelling. And King says it’s the white people who are producing the chaos.

This is King. One of the most interesting symmetries between Malcolm and Martin is the fact that Malcolm X, who I argue is Black America’s prosecuting attorney, was always charging white America with a series of crimes. We have the videotape of King talking to poor Black people in Marks, Mississippi. There’s a point where Andy Young says King is in tears listening. This is terrible. Marks, Mississippi. King says the way you are living right here in America, it’s a crime. That’s what King says.

So we go from Malcolm saying this is a crime. He’s that revolutionary. King’s our good guy. Right? So he’s the bad guy. And King is saying this is a crime. And King is talking about white people getting access to land through the Homestead Act. And Black people not getting their reparations, their 40 acres and a mule. And yet people are telling Black people to pull themselves up by their bootstraps. And so he says, we’re coming to Washington to get that check. Right. So this is extraordinary what happens in terms of the symmetry between both of these individuals. Both while they’re living but then certainly during the last three years of King’s life.

AC: So a final question. Before becoming a university professor, I taught high school history. And the question I have is, how should we teach about these two figures in a way that does more justice to their lives.

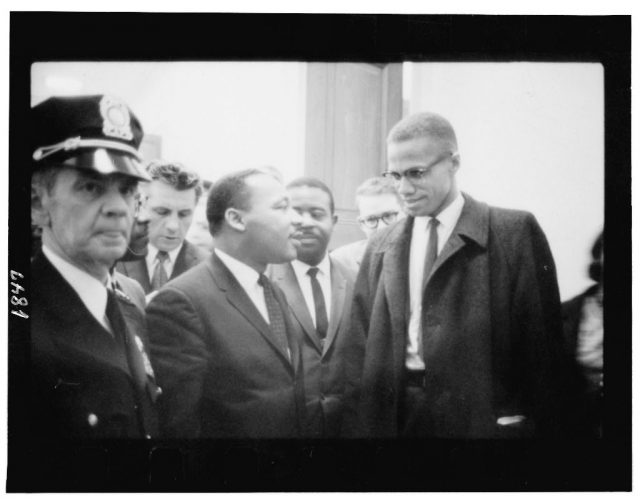

PJ: I think we should teach about them together. So this is really a dual biography. Whenever you tell students about one, you tell them about the other. It’s pretty simple to do because they live parallel lives. Malcolm’s born in 1925. King in 1929. Malcolm’s killed in 1965. King in 1968. So there’s not a lot of mental shuffling you have to do. And so I think you show students the way in which they interpret race and democracy differently based on the life experiences that they have. So you look at King: Morehouse College, had his father in his life. Malcolm: father was killed, trauma, foster home. While he’s in college, Malcolm is in prison. While King is in seminary, Malcolm’s in prison and they both come out and they’re activists, both men of faith. They become faith leaders. But then you look at how, how and why both of them imbibe this revolutionary moment in different ways. And then why do they start to converge? How and why they converge.

AC: Thank you for sharing your thoughts on two remarkable lives and a remarkable book.

Part I in this series is available here.

PENIEL JOSEPH holds a joint professorship appointment at the LBJ School of Public Affairs and the History Department in the College of Liberal Arts at The University of Texas at Austin. He is also the founding director of the LBJ School’s Center for the Study of Race and Democracy. His career focus has been on “Black Power Studies,” which encompasses interdisciplinary fields such as Africana studies, law and society, women’s and ethnic studies, and political science. His newest book, The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., was published in March 2020 and is available now.

More from Dr. Joseph on Not Even Past:

- The Sword and The Shield – A Conversation with Peniel E. Joseph (Part I)

- Stokely Carmichael: A Life

- Muhammad Ali helped make Black power into a global brand

- 15 Minute History Episode 90: Stokely Carmichael: A Life

- Watch: “The Confederate Statues at UT”

Consider reading as well:

- Violence Against Black People in America: A ClioVis Timeline

- Rising From the Ashes: The Oklahoma Eagle and its Long Road to Preservation

- Black Resistance and Resilience: Collected Works From Not Even Past

Featured Image Credit: MalcolmX and MLK, Jr., mural, E. W. alley view, N. of Manchester Ave. towards Cimarron, Los Angeles, California, 2010. (Vergara, Camilo J. Vergara Photograph Collection. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.