By Roy Doron

On November 19, 2016, President Barack Obama, speaking on the transition of power to Donald Trump said “once you’re in the Oval Office … that has a way of shaping … and in some cases modifying your thinking.” The 2016 election will undoubtedly be remembered as one of the most unconventional and even bizarre elections in American history. When Trump emerged victorious, he did so on a platform that promised to rethink virtually every aspect of American foreign policy, from free trade agreements to environmental treaties. Though the scope of Trump’s promises are unprecedented, his election was not the first time a candidate openly challenged U.S. foreign policy goals.

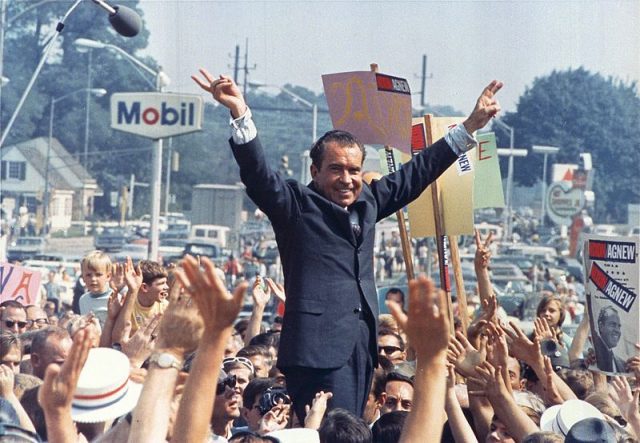

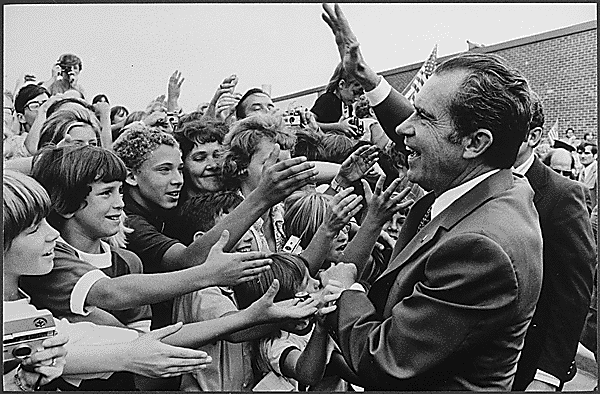

On September 8, 1968, Richard Nixon, then Republican candidate for president, issued a statement calling on the United States to take a central role in intervening in the Nigerian Civil War and the growing humanitarian catastrophe that was unfolding in secessionist Biafra. Titled “Nixon’s Call for American Action on Biafra,” the candidate called the Nigerian government’s war against Igbo secessionists a genocide and demanded that the United States take a leading role in stopping what he termed “the destruction of an entire people.” “While America is not the world’s policeman,” he declared, “let us at least act as the world’s conscience in this matter of life and death for millions.” (Kirk-Greene, 334-5). But the clarity of the candidate’s call to arms soon had to confront the realities of the office of President. The demands of America’s Vietnam-era foreign policy forced Nixon to abandon his personal sympathy for Biafra.

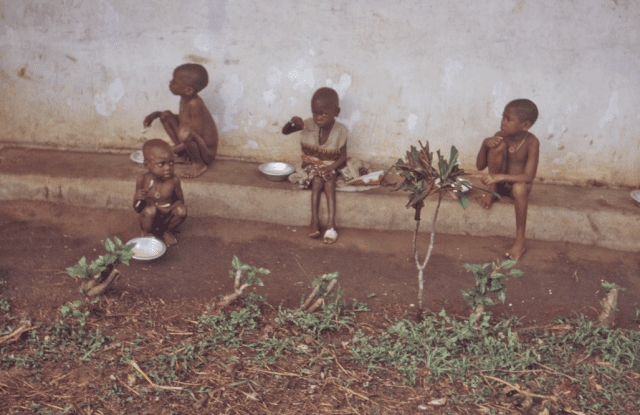

Many in the United States and in Nigeria and Biafra saw candidate Nixon’s statement as a call for active intervention in the war, which by the end of 1968 had turned increasingly in Nigeria’s favor. Nigeria’s civil war began when Biafra declared independence on May 30, 1967 after a protracted crisis that included two coups and ethnic violence that claimed the lives of thousands, mostly Igbo from Nigeria’s southeast. Though Biafra enjoyed several early successes, the war quickly turned into a protracted blockade against the Igbo heartland, with thousands of civilians dying every day from starvation and disease in the beleaguered enclave that Biafra had become.

To counter the military losses, the Biafran leadership embarked on a global public diplomacy drive spearheaded by MarkPress, a Swiss public relations firm owned by the American William Bernhard, calling the blockade and ensuing starvation genocide. MarkPress’ access to global media outlets helped the Biafrans garner significant attention in an already chaotic year in world history. The Tet offensive in February 1968 created a seismic shift in American support for the war in Vietnam, turning the majority of the population against it for the first time. This was followed by the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy only two months apart; the latter’s occurring in the middle of a tumultuous election campaign. In Europe, student protests in Paris almost brought down Charles De Gaulle’s government, while a Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in August ended Alexander Dubcek’s “Prague Spring.” However, with nightly news broadcasting images of starving children directly into homes around the world, many groups rallied to the Biafran side, with protests in cities around the world and benefit concerts featuring Jimi Hendrix and Joan Baez.

The Prague Spring was part of the global crisis of 1968 (John Schulze via Flickr).

These efforts, however, had little effect on government policies, because the Nigerians and their allies in the Organization of African Unity (OAU), eager to prevent a repeat of the Katanga Crisis in Congo, blocked most deliberations on the war in the United Nations, insisting that the matter was an internal African one. Biafra, led by the eloquent and charismatic Colonel Chukwuemeka Ojukwu, sought to use the humanitarian crisis to create a global outcry that would force Nigeria to come to terms with the secessionists and guarantee Biafra’s independence. Failing that, Ojukwu hoped for internationally recognized relief corridors that would be protected from the Nigerian military. However, any large scale international intervention would require either a ceasefire or a demilitarized zone. For the Nigerians, led by General Yakubu Gowon, any agreement for relief was preconditioned on Biafra renouncing secession and the ending of the war. In fact, despite frenetic efforts at two hastily convened OAU peace conferences in May and August 1968, the sides could not agree on either an end to the war or on any agreement to address the humanitarian concerns.

In the United States, the Lyndon Johnson administration was inundated with demands to help Biafra but could do little but support relief efforts led by the Red Cross, Joint Church Aid and Caritas. Walt Rostow, Johnson’s National Security Advisor, summed up the administration’s effort by saying “we are doing everything we can, which is very little.” Nixon’s statement, coming from a candidate that most believed would win the election in November, gave hope to many on the Biafran side that a new American administration would take a more active role in helping the beleaguered secessionists. For Ojukwu and Biafra, Nixon the candidate was a friend and they hoped that President Nixon would continue to be one.

Biafran leader Chukwuemeka Ojukwu (via Logbaby).

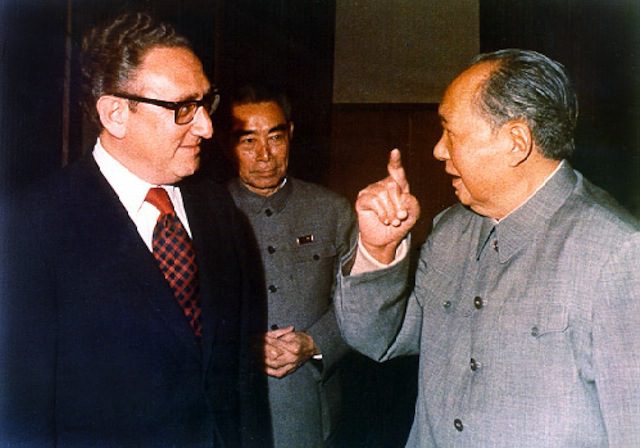

Though Nixon was personally sympathetic to Biafra, once he became president he could do very little to change the course of the conflict or to influence humanitarian efforts beyond what Johnson had done before him. In fact, like Johnson, Nixon attempted to assist in convening another round of peace talks, but, according to Nigerian historian George Obiozor, during a visit to London in February 1969, Nixon sacrificed his commitment to Biafra in order to secure British support for America in Vietnam. Nixon continued to personally support Biafra, despite his inability to translate it into policy. In one briefing document, he wrote in the margins “I hope Biafra survives!”

Candidate Nixon’s comments on Biafra showcase the limitations of a serious presidential candidate’s ability to transform foreign policy once they arrive in the White House. Many in Biafra hoped for a more interventionist United States and Nixon’s election gave hope for Biafra to hold out well into 1969, until it became clear that Nixon’s policy would closely mirror Johnson’s. When the war ended on January 15, 1970, the death toll, by most accounts, had reached a million people, most from the humanitarian crisis, and helped create organizations like Médecins Sans Frontières. Though the effects of Nixon’s 1968 comments cannot be quantified, his inability to translate them into policy illustrates the limitations of even the world’s most powerful executive.

![]()

Roy Doron (UT Austin History PhD, 2011) is an Assistant Professor of History at Winston-Salem State University. He is author, with Toyin Falola, of Ken Saro-Wiwa, part of Ohio University Press’ Short Histories of Africa and a forthcoming history of the Nigerian Civil War with Indiana University Press.

Sources:

H. M. Kirk-Greene, Crisis and Conflict in Nigeria: A Documentary Sourcebook (1971).

George A. Obiozor, The United States and the Nigerian Civil War : An American Dilemma in Africa, 1966-1970 (1993).

Brian McNeil discusses Humanitarian Intervention Before YouTube.

Brian McNeil explores #BringBackOurGirls: A History of Humanitarian Intervention in Nigeria.

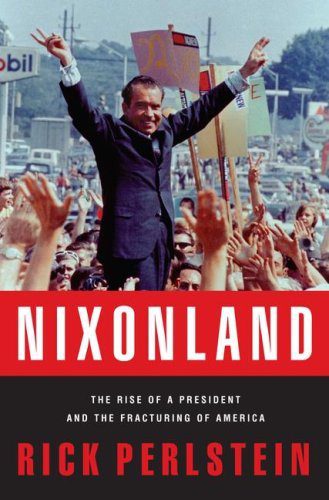

Dolph Briscoe IV reviews Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America by Rick Perlstein (2008).

![]()