By Abisai Pérez

By Abisai Pérez

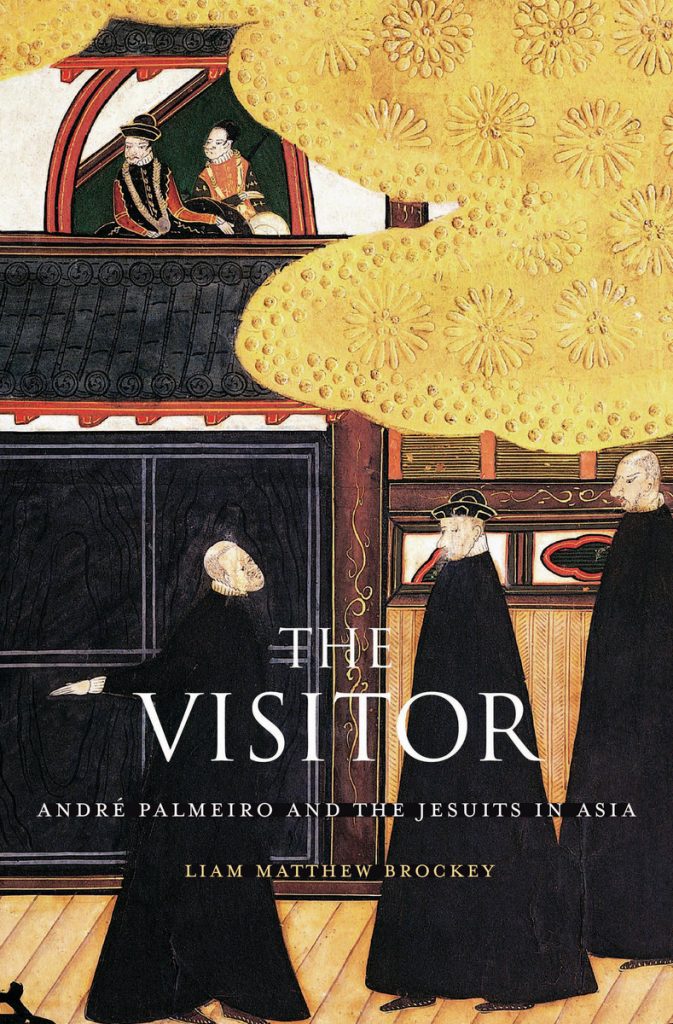

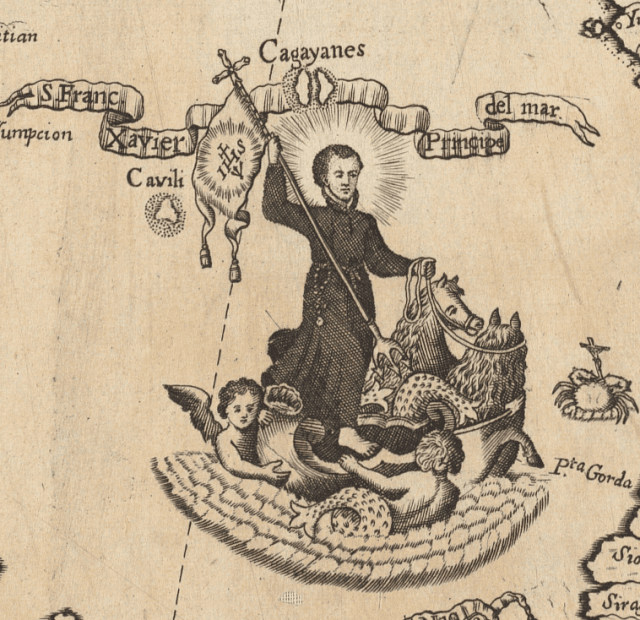

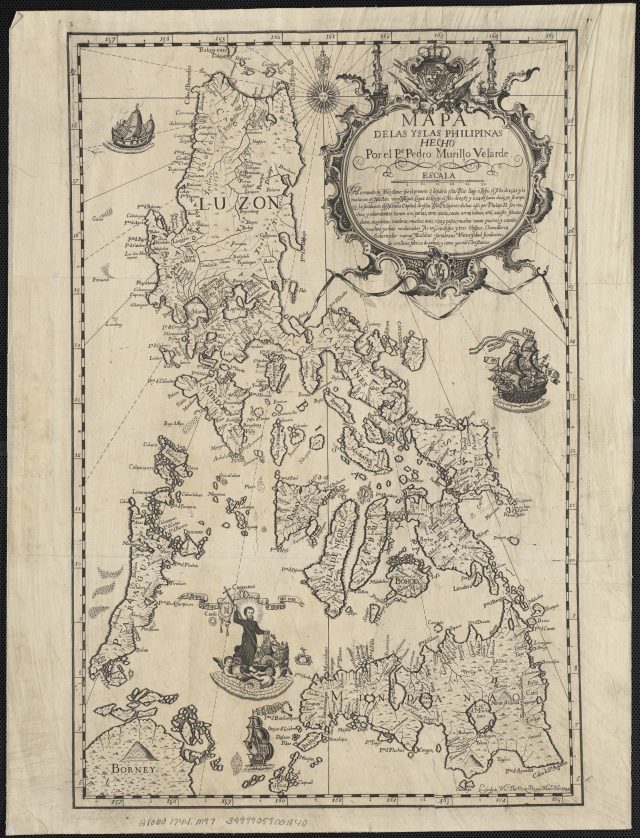

This book addresses the life of Jesuit father André Palmeiro (1569 [Lisbon] – 1635 [Macau]), who was the first inspector, or Visitor, of the Jesuit Company in India and East Asia with the mission of consolidating and expanding religious conversion in the remote regions of the Portuguese empire. Through the analysis of the Visitor’s experiences, Brockey describes the Jesuit order as an association of men from different countries who shared a feeling of fraternal union but also had contrasting views on how to carry out the preaching of the Gospel. In this book, the author dismantles the stories of solitary heroism in missionary work by evaluating the success and limits of the Jesuits’ strategies of adopting local customs, performing their mission in native languages, and debating with local intellectual elites about religious matters. Brockey argues that pragmatism and cultural adaptation, coupled with Portuguese colonialism, allowed the Jesuits to preach in the most remote regions but also confronted them with the orthodox branch of the Catholic Church.

Through the study of Palmeiro’s diary and correspondence with his superiors –most of the documents located in the Jesuit archive in Rome– Brockey vividly describes the challenges of the Visitor in India and China. He begins by describing Palmeiro’s formation as a scholar in Portuguese universities, where he stood out for mastering Catholic theology, and his efforts to learn how to run a religious order in a vast multicultural region during his journeys along the Malabar coast and in Sri Lanka. Then he turns to Palmeiro’s last years in Macau and inland China and analyzes the endeavors of the Visitor in reforming the conduct of his brethren according to Rome’s directions and providing support to his fellows in Japan, where the Jesuits faced extremely violent persecution.

Through this voluminous book, the author addresses three major issues that explain the success and limitations of the Jesuits in spreading Catholicism in Asia. First, while most historians have emphasized the stoic endurance and outstanding preparation of the Jesuits in matters of classical arts and theology, Brockey shows through the Visitor’s eyes that many of the missionaries were earthly men with human weaknesses and personal concerns. Far from being harmonious and focused on cultivating holiness, Brockey depicts the Jesuit missions as sites of conflict and instability. The book contributes to understanding that the dissensions within the order were not necessarily over religious matters based on personal ambitions, conflicts over jurisdiction with ecclesiastical hierarchies, and the unrealistic expectations of a young generation who hoped to convert thousands of souls by the mere act of preaching. Although Palmeiro was neither adventurous nor did he perform miracles like some of his predecessors, his pragmatic vision allowed him to successfully establish friendly ties with the royal courts of Ethiopia and the Mughal empire. Through diplomacy, the Visitor strengthened the proselytizing activities of the Jesuits in places where they only possessed rhetorical skills to survive.

Second, Brockey contrasts pragmatism with the Jesuit method of “cultural accommodation,” that is the adaptation of Catholic doctrine to local cultural conditions. The author challenges the vision that praises as “modern” the Jesuit method of conversion through the preaching in native languages and the embracing of local customs. Palmeiro’s involvement in two controversies over the method of cultural accommodation serves Brockey to explain the limits of that practice. First, when the Visitor arrived at Goa, he played an important role in the prosecution against father Roberto Nobili, who has adopted the lifestyle of Hindu Brahmans by wearing their robes, studying religious texts with them, and sharing meals with them that than his Catholic brethren. Portraying himself as a “Christian Brahman,” Nobili claimed the strategy would allow the conversion of members of the highest Hindu caste and consequently the rest of the population, but the ecclesiastical authorities accused him of heresy. Despite being a well-trained theologian, Palmeiro adopted a pragmatic attitude when he discredited that strategy. The Visitor resolved that its success was not only limited, but it was promoting a schismatic community given that converted Brahmans did not want to be subject to the authority of the Portuguese Church. Palmeiro adopted the same realistic approach when he later arrived in China. Facing the defiant attitude of his brethren who insisted on studying Confucian texts, using Chinese concepts to explain Catholic doctrine, and wearing silk robes like the local elite, Palmeiro prohibited those practices on the grounds that they were not gaining new souls for the Catholic cause. Despite their cultural accommodation, the Jesuits had become recognizable to the Chinese elite as learned men, but not as spiritual leaders. The cases of India and China, Brockey says, demonstrate that over time the Jesuits abandoned the method of cultural accommodation not because of the intolerance of ecclesiastical authorities but because of their practical ineffectiveness in expanding Catholicism.

The final issue that Brockey emphasizes is the close relationship between missionary work and Portuguese colonialism. The Jesuit presence in Asia would have been impossible without the commercial networks and the military presence of the Portuguese empire. The chaotic collapse of the Jesuit missions in Japan serves Brockey to demonstrate that the missionary success of the Jesuits depended heavily on colonial interests. The Visitor’s efforts to provide reinforcements to his fellows immersed in violent persecution in Japan were thwarted by the refusal of Portuguese civil authorities to confront the Japanese shoguns. Commercial interests proved to be more important than God’s desire and the Portuguese authorities did not want to lose the profits obtained from the commercial connection with Japan.

In the end, Mathew Brockey remembers that, contrary to the stories of heroism and miraculous conversion, the Jesuits in Asia always relied on the military support of the Portuguese empire. Not only the Chinese and Japanese experiences but also the parallel collapse of the Jesuit and the Portuguese empire in Asia reflected how the sword facilitated the preaching of the Gospel.

By

By