By focusing on the relationship between race and physical space, Nemser analyzes colonial concepts of race through an unexpected and innovative lens. His investigation of concrete structures and their effect on the creation of Mexico’s caste society spans the Spanish colonial period, from the sixteenth through the nineteenth centuries. Examining the dynamic among the indigenous, Spanish, and mestizo populations in Mexico City, Nemser claims that the conceptualization of race in colonial Mexico developed not only through interpersonal relationships but also grew out of the physical separation of peoples into distinct spaces.

Nemser focuses on four key spaces: religious congregations, mestizo schools, urban neighborhoods, and the city’s royal gardens. Ultimately, he finds that the physical separation of cultural groups implicitly created the subordinate status of non-Spanish populations. These racialized spaces, then, cultivated and institutionalized the inequality still found in Mexico today.

Nemser begins his discussion with the first Spanish efforts to separate indigenous populations into religious settlements known as congregations. He builds upon this foundational Spanish-indigenous dichotomy by then investigating the paradoxical existence of the mestizo and the segregation of Mexico City’s neighborhoods. Initially, biracial mestizos appeared to be the perfect mediators to bring the Spanish Catholic faith to indigenous populations. However, by the end of the sixteenth century, mestizos’ role in society had declined from missionary to vagabond. The subsequent separation of mestizos into different schools and neighborhoods further cultivated their reputation as dangerous and untrustworthy. Finally, Nemser experiments with a much more conceptual argument. Focusing on early modern Spanish understandings of botany, he asserts that the organization of the city’s botanical gardens throughout the nineteenth century acted as the predecessor to the scientific racism characteristic of the twentieth century. As imperial botanists in Mexico City separated plants into distinct spaces and micro-climates based on their biological characteristics, new concepts of biopolitics developed to address New Spain’s growing multiracial population.

Nemser structures his book in a way that capitalizes on accessibility to the reader. Each of the four core chapters discusses an increasingly more complex separation of space. The reader thus moves from concrete religious congregations to more abstract botanical divisions. This allows Nemser to delve into the complexity of racial separation in the colonial era without confusing readers. Finally, he utilizes the introduction and conclusion to tie these colonial concepts back to the modern era.

Infrastructures of Race relies on public resources such as administrative reports, academic debates, and urban surveys that allow Nemser to demonstrate how Spanish officials restructured urban spaces into racialized areas. Due to the nature of the sources, it is difficult to gauge the indigenous perspective. As such, Nemser’s analysis emphasizes the role of elite administrators in codifying race but cannot provide the indigenous response to such separation.

Infrastructures of Race provides a compelling discussion of the role of physical spaces in creating and solidifying definitions of race in society. Weaving a narrative between established theory and new research, Nemser has created an investigation that is both innovative and accessible to the reader. Taking care to consistently maintain the relevancy of the colonial caste system to modern Mexico, Nemser sheds light on both historical racial organization and contemporary institutional racism. Both academic and non-academic audiences will find Nemser’s work thought provoking.

Antonio de Ulloa’s Relación Histórica del Viage a la America Meridional

You may also like:

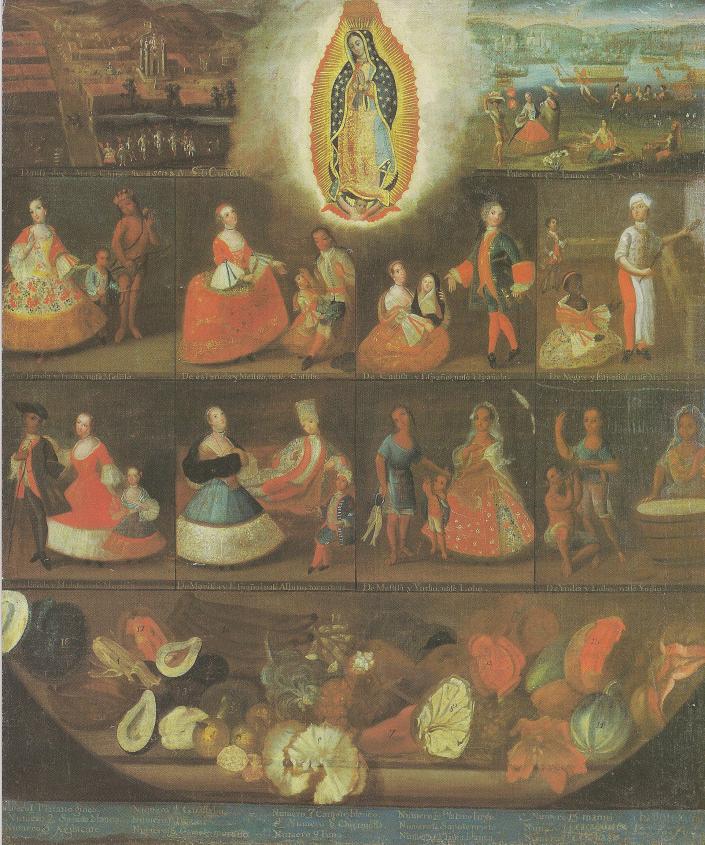

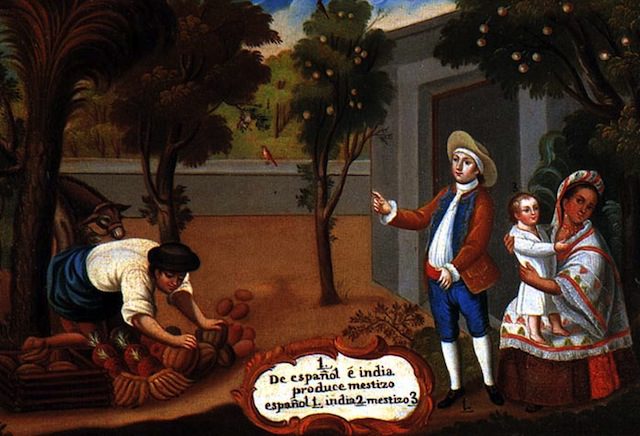

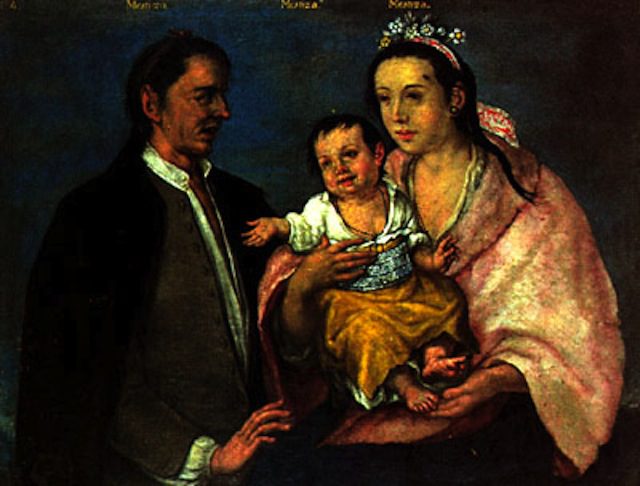

Casta Paintings, by Susan Deans-Smith

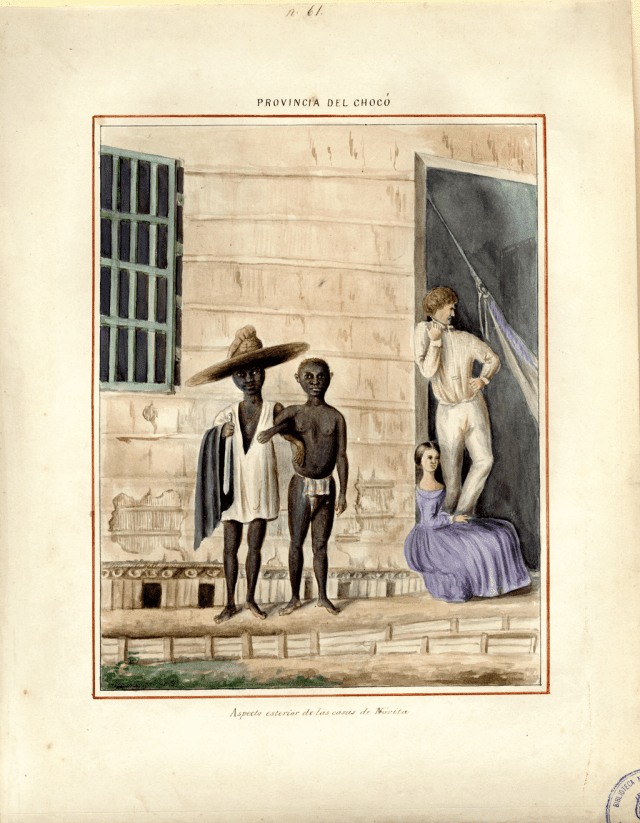

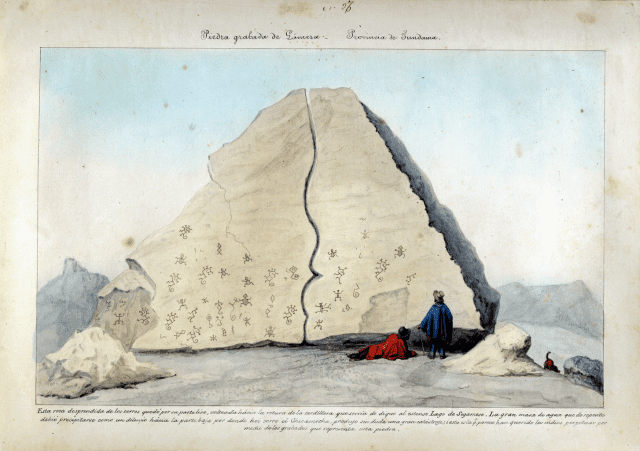

Mapping the Country of Regions: The Chorographic Commission of Nineteenth-Century Colombia by Nancy Applebaum, reviewed by Madeleine Olson

Imperial Subjects: Race and Identity in Colonial Latin America edited by Andrew Fisher and Matthew O’Hara, reviewed by Kristie Flannery