By Clay Katsky

Those who watch the television show The Americans share a secret with its protagonists: they are not a quintessential American couple living in the suburbs of D.C.; they are, in fact, spies for the Soviet Union. Set against the backdrop of a resurgent Cold War in the early 1980s, this serialized spy thriller and period drama follows the fictional lives of Elizabeth and Philip Jennings, played by Keri Russell and Matthew Rhys, who were born in Russia and trained as KGB officers to be “sleeper” agents in America. Activated when Reagan throws détente out the window, no one suspects that they have two deeply separated lives, one as travel agents who live in Northern Virginia with two young children, and a second filled with spy missions where they don disguises to seduce and assassinate targets and gather intelligence by blackmailing officials and recruiting assets. The dichotomy of their lives is by day marked by their genuine devotion to their children and to each other, and by night by the violent and frequently murderous clandestine missions directed by their Russian handlers. These Americans are not what they seem to be.

Kerri Russell and Matthew Rhys star in The Americans (via FX).

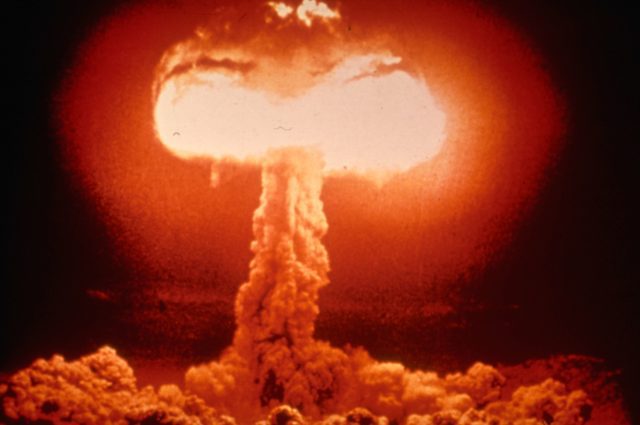

Ultimately, it is Reagan’s hardline against the U.S.S.R. that gives the show context. The first season begins as Reagan assumes the presidency and the third ends with the Jennings family watching his “evil empire” speech together. During the most recent fourth season, a family viewing of the TV movie The Day After, which is about nuclear Armageddon, adds another dimension to a subplot involving powerful bioweapons. The writers of The Americans do a good job of using 1980s popular culture and history to add contextual drama to the show, but sometimes ignore chronological specifics and the technical aspects of espionage tradecraft for the sake of storytelling. Regardless, the late Cold War works well as a general guide for the narrative arc of the series; the escalating tension between superpowers is directly responsible for the increasing drama in the lives of its main characters.

Perversely, The Americans sometimes makes you root for the enemy within. Fueled by terrific performances from Russell and Rhys, the Jennings can come off as sympathetic, and patriotic in their own way. Reminiscent of James Gandolfini in The Sopranos, these are bad people with redeeming qualities. She is an ideologically driven cold-blooded killer who is loyal to her family, while he is more sensitive and compelled by emotion, yet also capable of extreme violence. Both struggle with the conflict between their mission as spies and their duty as parents, which is a major plot device of the show. The tension of the first season is driven by their fear that the FBI will catch them. Right away evading capture is set up as synonymous with protecting their family. The second season expands on the theme of protecting their family from their world – after two other sleeper agents and their young children are murdered the Jennings fear they are next. The danger in the third season comes from within the family, with their daughter suspecting her parents are way more than just travel agents. And in the fourth season an assignment to steal bioweapons puts the whole world in jeopardy, pitting their loyalty to their country against their instinct to protect their children. Making the show about more than just spying and the Cold War, there are strong subplots involving the family’s next door neighbor, the FBI agent who works in the counter-intelligence division, and their daughter’s increasing devotion to Christianity, which comes to a head when she over shares with her pastor. The drama is about the characters, how they develop and how they react to one another in the context of the world around them.

The images of nuclear destruction in The Day After (1983) were troubling to many American families (via Wikimedia Commons).

In The Americans, history is used as the setting. The show underscores Reagan’s determination to defeat the forces of Communism using clips from his speeches – as Soviet agents, the Jennings find the rhetoric palpable. And at their house, the news always plays in the background at night, helping to give a timeline of events while also highlighting the television culture of the time – pop culture events like David Copperfield making the Statue of Liberty disappear are drawn on to both diffuse the tension and offer social nostalgia. But the headlines are also used to drive the drama. When Reagan gets shot, the Jennings go on high alert because they are not sure if their government was involved; and when Yuri Andropov, their former leader at the KGB, takes power in 1982, they know their lives are about to get busier. The writers incorporate the shift towards renewed hostilities that occurred during the late Cold War in order to give the viewer the sense that the Jennings mission is important. The rivalry between the superpowers could have spun out of control very quickly and at any moment, and the “the Americans” are caught in the middle of it.

The show begins as Reagan kicks the Cold War into high gear in 1981 and it will end with the collapse of the Communist superpower – having been renewed for a final two seasons, the story will be told to its conclusion. The Soviet fear of the Strategic Defense Initiative, Reagan’s anti-ballistic missile “Star Wars” project, is a centerpiece of the first few episodes. In reality, 1981 is too early for the Russians (or even Reagan) to be thinking seriously about SDI, but it works as an easy set up. At that time, however, it was mostly Reagan’s rhetoric that threatened to turn the Cold War hot. Nicaragua comes to the fore in the second season, again a little early in terms of chronology, but it works well because the Jennings’ sympathy for the Sandinista movement helps humanize them. Oliver North is credited as a technical advisor on an episode where the Jennings infiltrate a Contra training base. Empathy for the Jennings continues to build as they assist the anti-apartheid movement during the third season, while meanwhile the seeds of mistrust in their government are sown with the opening of the war in Afghanistan. In the fourth season, as their government pushes them to recruit their own daughter, the Soviet mismanagement of that war feeds their growing disillusionment and dovetails with a risky mission to acquire an apocalyptic bioweapon. While this past season was it’s least historically based, it was also its best because it dealt with larger, more existential issues.

A Soviet Spetsnaz (special operations) group prepares for a mission in Afghanistan, 1988 (via Wikimedia Commons)

The technical focus of the show is on tradecraft, not history. The thrills come from watching the spies operate; and from making dead drops and cultivating assets to planting listening devices and evading surveillance, the Jennings are very busy. But the show’s most exciting aspect is also its least plausible. It is hard to believe that such well-placed agents would be used as workhorses for the KGB. Especially in the first two seasons, the Jennings juggle multiple assignments at the same time and go on a wide variety of missions – simultaneously they are assassins, saboteurs, master manipulators, and experts in surveillance, counterespionage, and combat. As valuable as they would have been to their government, the Jennings are asked to take too many risks and expose themselves too often. But even in its most exaggerated aspects, The Americans feels realistic due to the expert performances from Russell and Rhys, who are so believable in their roles as skilled spies and as doting parents that one cannot help but trust in their inhuman ability to be an expert in anything they need to be.

Overall, The Americans is a highly engaging and richly thought out show set in the waning years of the Cold War. It is very exciting to watch two highly trained KGB operatives as they navigate the complexity of staying ideologically loyal to their cause while raising an American family and living a lie. People who remember the 1980s firsthand will enjoy the references and set pieces, and anyone who likes spy thrillers will be instantly hooked on the slow boiling but constant action and drama. It will be interesting to see how the upcoming fifth season incorporates the Able Archer war scare, when the Soviets mistook NATO war games for the start of real life a nuclear engagement. Will it be the Jennings who witness an increase in late night pizza deliveries to the Pentagon and report back to Moscow that nuclear war is imminent? They seem too savvy to drop the ball like that. But what will happen in the end? Will they survive or be caught by the FBI, or will they get called back to Russia to be punished for some failure or perceived disloyalty?

![]()

Read more by Clay Katsky on Not Even Past:

Kissinger’s Shadow, By Greg Grandin (2005)

You may also like:

Simon Miles reviews Reagan on War: A Reappraisal of the Weinberger Doctrine, 1980-1984, by Gail E. S. Yoshitani (2012)

Joseph Parrott examines The Rebellion of Ronald Reagan: A History of the End of the Cold War, by James Mann (2010)

![]()