Interviewed by Amber Abbas

Center for Advanced Study, Department of History, Aligarh (June 28, 2009)

Transcript:

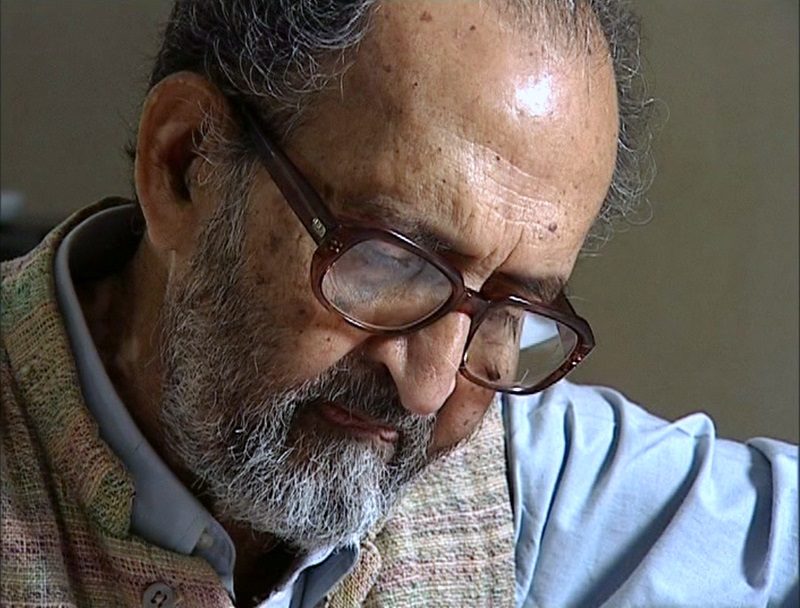

Context Notes: Professor Irfan Habib is probably the best-known professor of History in Aligarh. He was a young student, in the Intermediate classes during the 1940s. His father, Mohammad Habib was the leader of the progressive factions at Aligarh. Irfan Habib is an Emeritus Professor of the Dept of History but he still appears daily in the department where he sits in the office of Professor Shireen Moosvi and interacts with all of the students, other professors, Communist party activists and others who move in and out of the office throughout the day. Irfan Habib always provides hospitality to these guest, endless cups of tea and biscuits. On many occasions I had the opportunity to sit in the office and transcribe stories he would share in English or in Urdu with the people who came and went. It was some time before I could convince him to sit down with me for a formal interview because he was very skeptical of the methodology of my research, being as he is, a historian of medieval India and deeply invested in the investigation of documentary sources. When I finally did meet him he asked me to meet him in his own office, down the hall, a small cupboard of a room, which he referred to as his “Hole Office.”

Amber Abbas: What changed at AMU around partition? Obviously a lot of people left, but what did that look like?

Professor Irfan Habib: Well, first of all, one of the strengths of institution we didn’t notice, that admissions were on time, classes were held, a teacher disappears was replaced immediately by another teacher. Classes were held.

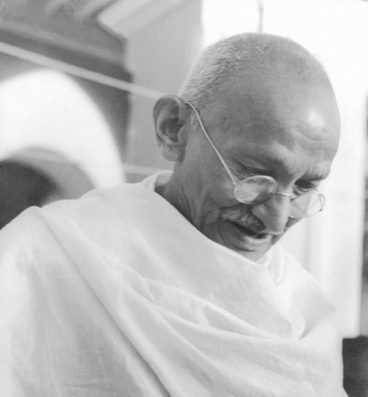

Secondly, Gandhi’s fast and martyrdom had much to do with the recovery. When Gandhi died I would expect 20% of the people in the university were from Pakistan. They had remained here to complete their second year, that is Intermediate Final, their fourth year B.A. Final and their M.A. Final. Because they had already done one year and they wanted to complete it. They didn’t know that riots will close us, they came in July when it opened the riots broke out in August. So they were here. So they were here. They were very concerned, you can understand, all of us were concerned, about the slaughter, and so Gandhi became the one man between slaughter and protection. We were coming from Lucknow and we heard at Hattras station that Gandhiji had been assassinated. So the next day my father with four or five people, you know, nationalists were very few at that time, Muslim Nationalists. But we were about ten or twelve, then some others joined us. So we went; I was a first year student. We went and stood in the SS Hall Gate, from this side, Bab-ul-ilm (Gate of Knowledge) or something like that. And soon students began collecting. HUGE crowd! At that time there must have been around 2500 students [in the whole university], then the number declined. HUGE crowd! We were asked to wait for V.M. Hall people. We went to City. Actually, that was my first impression of a demonstration. There were communists also demanding execution of RSS leaders. Hindu Sabha, nehin, RSS or Hindu Sabha, Phansi Do! Phansi Do! I forget the title, the slogans.

AA: So you left for City after you knew who the assassin was?

IH: No, that was announced on the radio immediately! Totally. I mean, his name was announced repeatedly on the radio. That it’s Godse and he’s a Hindu Mahasabhite. Oh, it was announced. Only Hindustan Times in an edition said it was suspected to be a Muslim, but they apologized later on, Devdas Gandhi apologized and Nehru was very annoyed. So that was a remarkable demonstration. And all these Pakistanis were there. And then the refugees started coming at almost the same time. They were admitted. I still remember Punjabis from Pakistan mixing with Sikhs, you know, shanyartis. Collecting things for them. Even in this demonstration there were Sikh students and Punjabis from Pakistan. And Hindus, of course, Hindus are not marked out. So that was a second feature, was how sharnyartis fitted in. No—not a single incident took place in the university between Muslim students and sharnyartis.