By Cali Slair

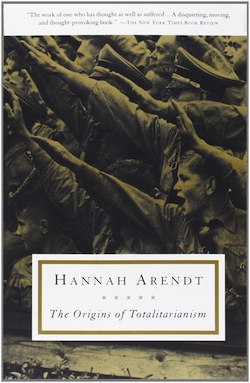

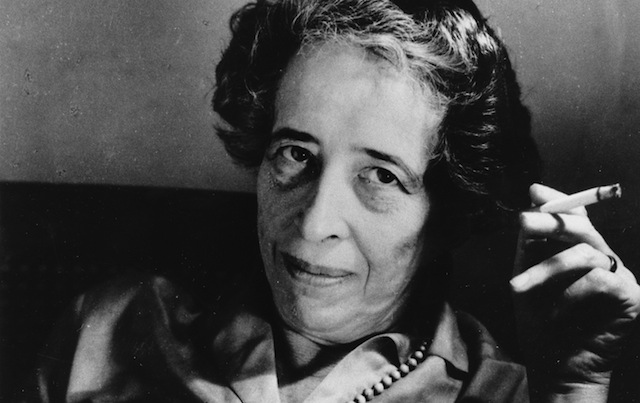

While totalitarianism did not first emerge in the twentieth century, the totalitarian states of Nazi Germany under Adolf Hitler (1933-1945) and the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin (1924-1953) were distinct. In The Origins of Totalitarianism Hannah Arendt (1906-1975), one of the most influential political philosophers of the twentieth century, seeks to explain why European populations were amenable to totalitarianism in the twentieth century and to identify what factors distinguish modern totalitarian regimes. Arendt was born into a German-Jewish family in Hanover, Germany in 1906 and in 1933, fearing Nazi persecution, she left Germany. The Origins of Totalitarianism is Arendt’s attempt to better understand the tragic events of her time.

In The Origins of Totalitarianism Arendt explores the histories of anti-semitism and imperialism and their influence on the development of modern totalitarian regimes. Arendt argues that anti-semitism, race-thinking, and the age of new imperialism from 1884-1914 laid the foundation for totalitarianism in the twentieth century. Arendt traces how racism and anti-semitism were used as instruments of imperialism and nationalism in nineteenth-century Europe. Arendt shows that imperialism and its notion of unlimited expansion promoted annexation regardless of how incompatible a country may have been. Nationalism developed along with imperialism, and foreign peoples who did not fit in with the nation were oppressed. Modern totalitarian regimes, aware of the efficacy of these instruments, used them in pursuit of their singular goals.

Arendt argues that the origins of totalitarianism in the twentieth century have been too simplistically attributed to nationalism, and totalitarianism has been too easily defined as a government characterized by authoritative single-party rule. Arendt also argues that scholars and leaders have mistakenly equated nationalism and imperialism. Arendt rejects the notion that a dictatorship is necessarily totalitarian. Dictatorships can be totalitarian, but they are not inherently totalitarian. Totalitarian governments are characterized by their replacement of all prior traditions and political institutions with new ones that serve the specific and singular goal of the totalitarian state. Totalitarian governments strive for global rule and are distinguished by their successful organization of the masses. In fact, Arendt argues that totalitarianism is significantly less likely to originate in locations with small populations.

Arendt also argues that modern totalitarian regimes are defined by their use of terror. Totalitarian terror is used indiscriminately; it is directed at enemies of the regime and obedient followers without distinction. Arendt argues that, for modern totalitarian regimes, terror is not a means to an end, but an end in itself. Arendt states that modern totalitarian regimes used alleged laws of history and nature that noted for example, the inevitability of war between chosen and lesser races, to justify terror. Arendt also argues that the bourgeoisie’s rise in power eroded the political realm as a space for freedom and deliberative consensus and contributed to the amenability of populations to totalitarianism.

According to Arendt, the appeal of totalitarian ideologies is their ability to present a clear idea that promises protection from insecurity and danger. After World War I and the Great Depression, societies were more receptive to these ideas. These ideas are fictional and the success of totalitarianism hinges on the regime’s ability to effectively obscure the distinctions between reality and fiction. One way this is accomplished is through propaganda.

Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism is an influential work that takes on the difficult task of trying to understand the devastating rise of Nazi Germany and Soviet Stalinism.

You may also like these articles in our Social Theory series:

Abikal Borah on Dipesh Chakrabarty’s Provincialising Europe

Joshua Kopin discusses Walter Benjamin on Violence

Ben Weiss explain’s Slavoj Žižek’s theory of Violence

Jing Zhai on Jacques Derrida and Deconstruction

Charles Stewart talks about Foucault on Power, Bodies, and Discipline

Juan Carlos de Orellana discusses Gramsci on Hegemony

Michel Lee explains Louis Althusser ideas on Interpellation, and the Ideological State Apparatus

Katherine Maddox on Ranajit Guha’s ideas about hegemony