It’s an old question: how did northwestern Europe, seemingly an economic backwater around 1400 CE, rise to trade dominance in just a few centuries? In Going the Distance: Eurasian Trade and the Rise of the Business Corporation, 1400-1700, Ron Harris offers a fresh answer. He traces the financial tools and organizational forms in Eurasia that offered alternatives to—or building blocks for—the business corporation. By comparing these organizational forms in China, India, the Middle East, and Western Europe, Harris argues that the business corporation was formed in response to the structural and commercial weaknesses, rather than the strengths, of England and the Dutch Republic.

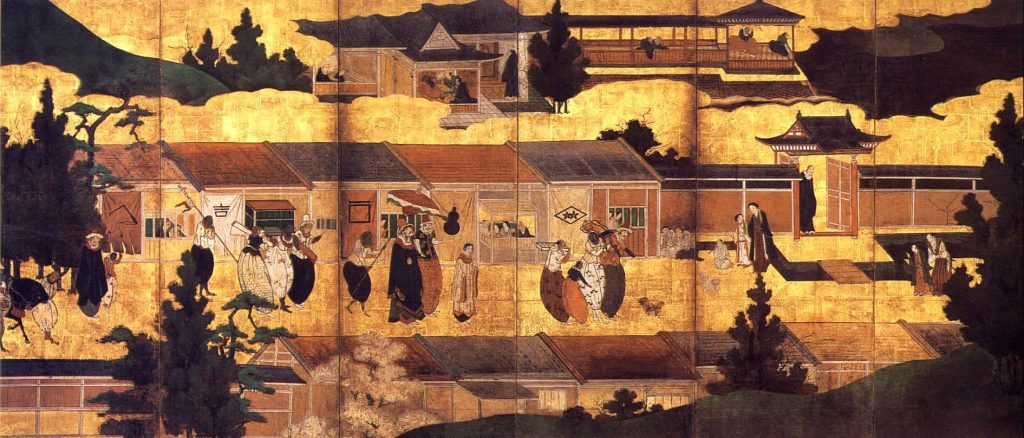

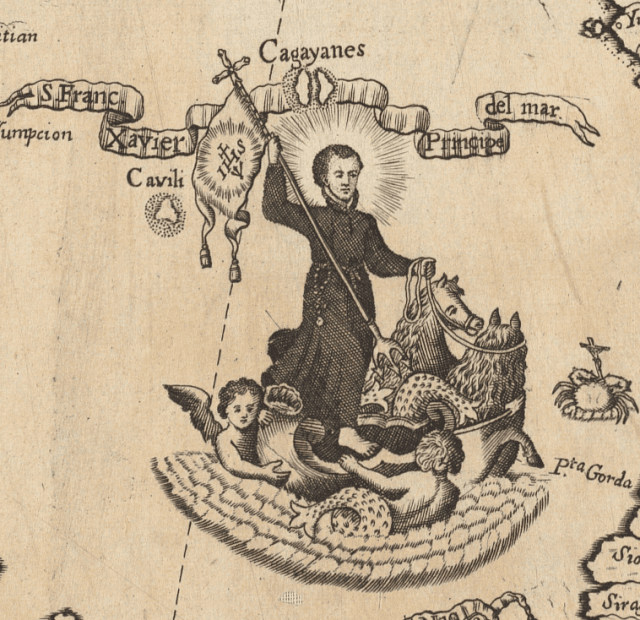

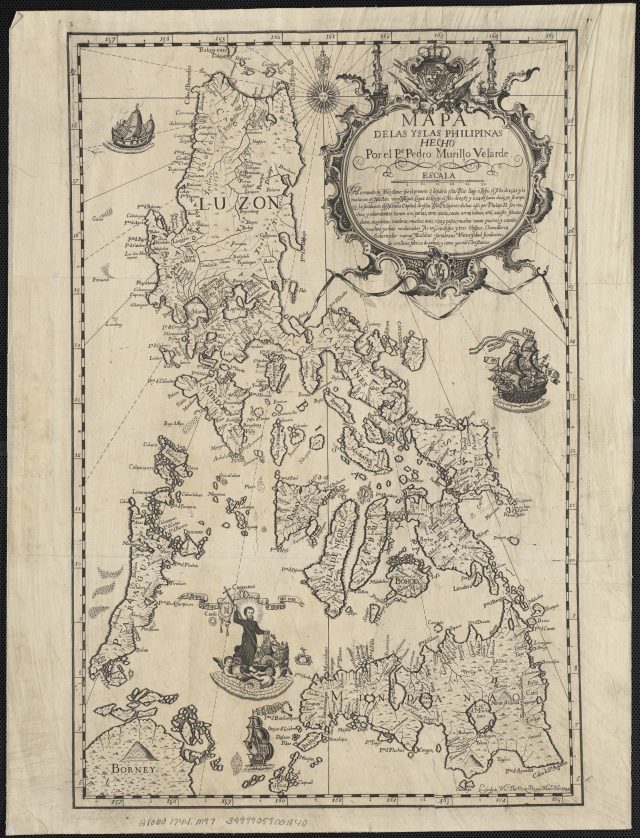

Harris underpins this complex discussion with a clear organizational structure. Part I provides the context of premodern Eurasian trade and its gravitational center, the Indian Ocean. From at least the second century CE, regular maritime trade networks connected Rome to Indian Ocean markets, while ancient Silk Routes across Central Asia reached their fullest extent under Mongol rule in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Following the disintegration of the Western Roman Empire, Europeans were largely cut off from these trade routes. In contrast to previous theorists, Harris argues that Europeans possessed no substantial technological or military advantages to overcome this commercial marginalization. In a position of relative weakness, Europe was more often an importer than an exporter of business innovations.

In Part II, Harris considers the “organizational building blocks” that determined the possibilities of Eurasian trade before 1400.[1] The itinerant trader, the bilateral trade relationship (established through an agency contract or loan), and the merchant ship with its specialized personnel appeared independently in every major region. More complex organizational forms migrated from distinct points of origin. Harris attributes the spread of two major organizational forms to Islam, namely the funduq or caravanserai and the qirad.

Tracing its roots to ancient Greek traveling lodges, the Arab funduq followed Muslim conquerors and traders to North Africa, southern Europe, and Central Asia. These outposts provided lodging, sustenance, protection, and trading opportunities for merchants; they were a boon to trade networks across the Silk Routes and beyond. The qirad, on the other hand, was a “bilateral limited partnership.”[2] Particularly useful to Muslims forbidden to profit from interest-bearing loans, it brought investors into contact with traveling merchants in a particular way: the investor would contribute capital to a shared “pool of assets” that the traveling merchant would manage on a trading mission.[3] When the traveler returned, he and the investor would divide the profits, usually claiming 50% each. It is likely that the Arab qirad inspired the Italian commenda.

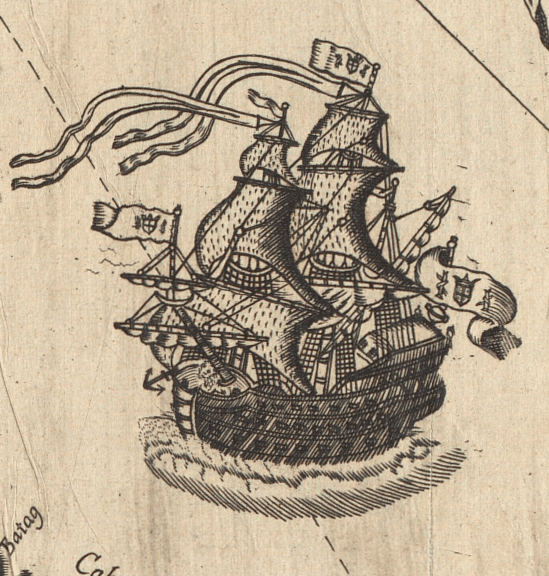

Part III highlights three Eurasian institutions that effectively dominated trade before the business corporation. The first was the family firm. For example, the Pu lineage in southern China monopolized official government positions that provided near-exclusive access to maritime commerce under the Yuan dynasty. In Mughal Gujarat, the Ghafur and Vora family firms were less connected to the state apparatus and had the freedom to send ships and agents across the Indian Ocean world. The Fugger family in Augsburg rose from peasant origins to great wealth in a few generations, thanks to the flexible use of partnership contracts and other tools. The second institution was the merchant network, which usually involved the family firm but extended to other merchants within a particular region or ethno-religious group. Jewish networks based in Cairo or Livorno and the Armenian network in New Julfa made use of many of the financial building blocks discussed in Part II. The third institution was the state-supported trading expedition. The Ming dynasty voyages of Admiral Zheng He and the Portuguese Carreira da Índia are key examples.

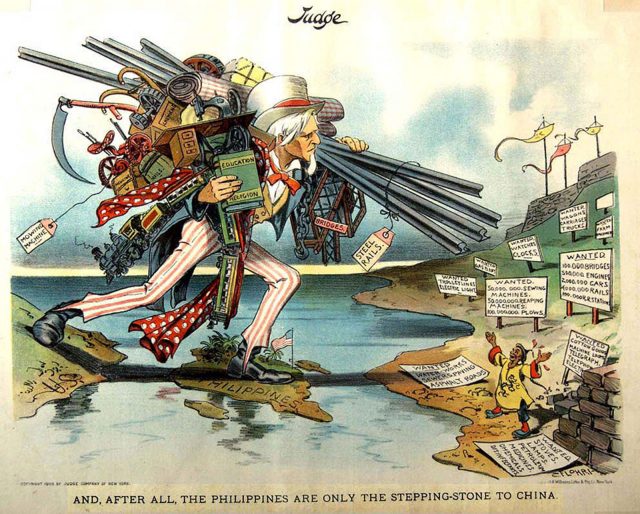

According to Harris, each of these organizational forms was outpaced by the European business corporation, first manifested in the English and Dutch East India Companies that were founded at the turn of the seventeenth century. In Part IV, Harris explains that the business corporation, a distinctly European form, grew from the legal and financial partnerships that the clerics and religious orders of the medieval Roman Catholic Church established to protect Church property. The emergent legal “corporate form” was adopted by chartered towns and guilds.[4] In sixteenth-century England, as merchant guilds evolved into regulated corporations and eventually business corporations, four financial tools were added: joint-stock equity, investment lock-in, interest transferability, and protection from state expropriation. Limited liability would only be introduced to the corporation in the eighteenth century. Harris argues that this innovative combination of features was a pragmatic response by the English and the Dutch to the “significant entry barriers” they faced in accessing Eurasian trade because of their marginal location, lack of attractive export goods, and late entry to the game.[5]

Two relatively brief chapters are devoted to the early organizational history of the English East India Company (EIC) and the Dutch East India Company (usually known by its Dutch acronym, VOC). Most importantly, Harris contrasts the oligarchic management of the VOC with the more egalitarian structure of the EIC, in which all shareholders were entitled to voting rights as well as access to company news and accounting. In any case, both companies raised significantly more capital from a larger pool of investors than any previous venture in Eurasian history. Because they achieved the broad, impersonal cooperation of investors in political contexts that resisted the expropriation of company funds by the state, the EIC and VOC offered “the ultimate organizational solution” to the problems of long-distance trade.[6]

But why did the business corporation not develop elsewhere in Eurasia, and why did the form not migrate to the Middle East, India, or China until the modern period? Harris sees the corporation as an embedded European institution that did not migrate because of three possible factors: (1) a lack of demand in other locations, (2) the availability of alternative institutions, or (3) political resistance to its migration. In the Middle East, for example, there was little distinction between the state and the religious establishment, which jointly dominated institutions that may have otherwise benefitted from the corporate form—especially towns and guilds. The waqf (or religious endowment) shared certain features with the corporation through the pooling and protection of assets, but it did not—and could not—engage directly in trade. In South Asia, there was little demand for the corporation because the subcontinent existed at the center of historic trade networks and produced the most valuable goods that were sought by others. In China, Harris suggests that “[t]here was no space between the state and the family.”[7] Thus, the state monopolized trade and the family lineage was limited to pooling and protecting its own assets in the manner of a trust, rather than a business corporation.

A word of caution: Going the Distance does not make for light reading. Furthermore, regional specialists may take issue with the inevitable gaps and generalizations that accompany all comparative history. For example, Gregory Schopen’s Buddhist Monks and Business Matters has much to say about a powerful corporate form—the Buddhist monastery in South Asia—that bears comparison to the supposedly unique medieval European equivalent.[8] Such work is notably absent from Harris’s analysis. Yet, viewed as a whole, Going the Distance is a compelling piece of comparative history that also takes the trouble to incorporate detailed case studies on the basis of primary sources. Informed readers will recognize Harris’s intervention in scholarly debates about the so-called Great Divergence of European and other global economies. Some may find his treatment of the joint-stock business corporation too sanguine, in spite of his explicit “preemption concerning Eurocentrism.”[9] Ultimately, Harris resists the pressure to make absolute claims about the historical legacy of the business corporation and concludes his book with an expression of ambiguity: “Was the organizational revolution a precondition to the financial revolution, to the fiscal-military state, and to the British Empire? Possibly.”[10]

[1] Ron Harris, Going the Distance: Eurasian Trade and the Rise of the Business Corporation, 1400-1700 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020), 63.

[2] Ibid., 110.

[3] Ibid., 132.

[4] Ibid., 254.

[5] Ibid., 273.

[6] Ibid., 373.

[7] Ibid., 364.

[8] Gregory Schopen, Buddhist Monks and Business Matters: Still More Papers on Monastic Buddhism in India (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2004).

[9] Harris, 11.

[10] Ibid., 376.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.