by Matt Tribbe

by Matt Tribbe

Fifty years ago, in the spring and summer of 1961, a brave group of activists dared to commit one of the most dangerous acts imaginable at the time: they blatantly obeyed the laws of the United States. Knowing full well that a majority of white Southerners did not accept federal desegregation orders, and that the Kennedy administration was reluctant to enforce them, hundreds of civil rights activists nonetheless embarked on Southern-bound buses in order to test a recent Supreme Court decision forbidding segregation at interstate bus terminals. This was not necessarily civil disobedience, disobeying unjust laws for moral and political ends. Rather, as Raymond Arsenault notes of these “Freedom Rides,” it was a “disarmingly simple act.” The Freedom Riders would just behave as if Supreme Court rulings were, in fact, the law of the land, and then respond nonviolently to the inevitable bloodied heads, broken bones, firebombings, and intimidating prison stints that greeted their attempts to sit in interracial pairs on buses and integrate restaurants, waiting rooms, and even shoe-shine stands at terminals in the Southern states. Though few anticipated the full ferocity of the organized white resistance in the Deep South, the Riders hoped that such disturbing scenes of brutality against nonviolent activists who were simply expressing their constitutional rights would shock the nation out of its complacency on Southern segregation.

Arsenault offers an engaging chronicle of the Freedom Rides in this new, abridged edition of his definitive 2006 account. He places the Freedom Rides in their larger historical trajectory, revealing their antecedent in an earlier attempt to desegregate interstate buses in 1947 and examining various civil rights strategies and initiatives over the 1950s that contributed to the decision to launch the campaign. But this book is about a specific moment in time—the summer of 1961—and Arsenault uses his gripping narrative to explore many broader issues confronting the civil rights movement and the nation as a whole in that particular year. We see in all their complexity, for example, the often-strained relationships and clashes over strategy between various civil rights organizations. Most established groups like the NAACP were critical of these provocative actions, yet it was that organization’s unenforced court victories that made the Freedom Rides both possible and necessary. Another major theme that Arsenault follows over the year is the Kennedy Administration’s consternation at the Rides. Wary of the embarrassment they might cause the United States at this pivotal moment in the Cold War, just after the Bay of Pigs fiasco and shortly before Kennedy’s first meeting with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, Attorney General Robert Kennedy constantly urged the Riders to accept a “cooling-off period” so that the administration could deal with Southern segregation in a more deliberate manner. But as the Riders well knew, “cooling off” meant returning to the unacceptable status quo. Indeed, to the Kennedys’ great chagrin, they were perfectly willing to cause a national crisis in order to force the administration to finally take meaningful action against segregation.

As the emphasis in the book’s title suggests, however, what comes across most vividly in Freedom Riders is the dogged determination of the four-hundred-plus activists who volunteered to continue the Rides over the summer, even after it was clear that violence and incarceration in Southern jails were unavoidable. Arsenault ably recreates all of the savage beatings and unenviable dilemmas faced by these men and women who risked their well-being, their freedom, and even their lives in order to force America to live up to its principles.

Readers wishing to learn more about this often-overlooked campaign of the civil rights movement and the very diverse group of people who pulled it off; about the movement’s decisive shift toward the strategy of non-violent direct action; about the massive headaches this endeavor caused the Kennedy Administration; about the horrors that faced anyone who challenged Deep South racial mores in the early 1960s; and, perhaps most important, want this story told with both nuance and flair, will enjoy Freedom Riders.

The fiftieth anniversary of the freedom rides this year has brought out a number of moving books, films, and other website materials:

PBS “American Experience,” film, Freedom Riders

The website for the PBS “American Experience” film, Freedom Riders, includes historical material, maps, biographies, teaching guides, and more.

James Farmer, one of the organizers of the Freedom Rides, interviewed by Terry Gross on NPR’s “Fresh Air.”

Raymond Arsenault interviewed by Terry Gross on NPR’s “Fresh Air”

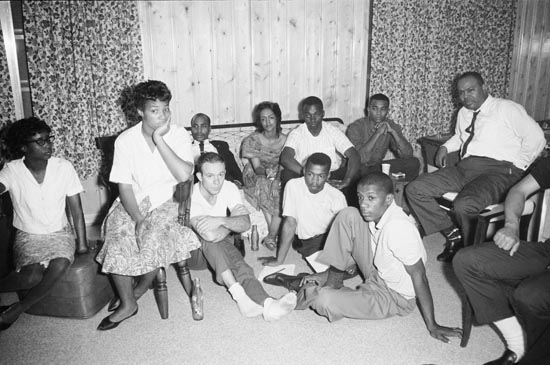

Group photograph: Freedom Riders at the home of Dr. Richard Harris after the church siege in Birmingham, AL. Included are Lucretia Collins (center), James Farmer (far right) and John Lewis (ground, right).

Credit: Johnson Publishing Company

From American Experience, Freedom Riders (fair use)

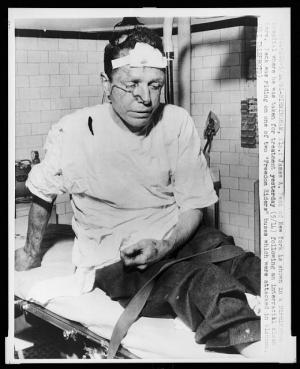

Photograph of James Peck seated on a hospital gurney in Birmingham, Alabama following attack on a Freedom riders bus. By Joseph M. Chapman Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Jacoby does this through a study of the

Jacoby does this through a study of the

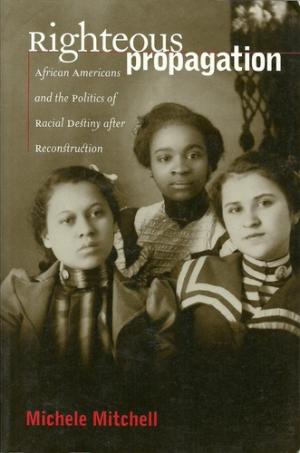

In the prologue, Mitchell explains, “No longer divided into categories of ‘free’ or ‘slave,’ people of African descent acted upon assumptions that the race was unified, that institution building was possible, that progress was imminent.” This optimism shaped ideas about collective identity, destiny, and improvement of the race.

In the prologue, Mitchell explains, “No longer divided into categories of ‘free’ or ‘slave,’ people of African descent acted upon assumptions that the race was unified, that institution building was possible, that progress was imminent.” This optimism shaped ideas about collective identity, destiny, and improvement of the race.