By Charley S. Binkow

February is Black History month. It is a time for remembrance and reflection for all Americans, but for Historians it is also a rich period for study and research. iTunes U, the academic branch of Apple’s iTunes store, is featuring a vast collection of first-hand oral histories, interviews, and lectures on the extensive history of African Americans.

There are over two dozen podcasts and each one offers a unique perspective on black history: “The Louis Armstrong Jazz Oral History Project” explores the world of African American Jazz, The Gilder Lehrman Institute offers a diverse lecture series on the post Civil War age, and Stanford’s “Modern Freedom Struggle” collects videos on political thought during the Civil Rights movement. The most powerful, collection is Duke University’s “Behind the Veil,” which compiles 100 interviews with African Americans who experienced firsthand the world of segregation in places like Birmingham, New Orleans, Memphis, Albany (GA), and Muhlenberg County. These interviews are as personal and interesting as they are diverse. All the podcasts are free on iTunes and are well worth perusing.

There are over two dozen podcasts and each one offers a unique perspective on black history: “The Louis Armstrong Jazz Oral History Project” explores the world of African American Jazz, The Gilder Lehrman Institute offers a diverse lecture series on the post Civil War age, and Stanford’s “Modern Freedom Struggle” collects videos on political thought during the Civil Rights movement. The most powerful, collection is Duke University’s “Behind the Veil,” which compiles 100 interviews with African Americans who experienced firsthand the world of segregation in places like Birmingham, New Orleans, Memphis, Albany (GA), and Muhlenberg County. These interviews are as personal and interesting as they are diverse. All the podcasts are free on iTunes and are well worth perusing.

The collection is of value for everyone, from professional historians to amateur history buffs. On top of the primary sources, subscribers can hear engaging and thought provoking lectures from renowned scholars like Eric Foner and James O. Horton. iTunes, is also offering customers a wide selection of outside reading options relating to the topic of Black History, with titles such as The Color Purple, Beloved, Fredrick Douglass’s My Escape from Slavery and Howard Zinn’s On Race.

The collection is of value for everyone, from professional historians to amateur history buffs. On top of the primary sources, subscribers can hear engaging and thought provoking lectures from renowned scholars like Eric Foner and James O. Horton. iTunes, is also offering customers a wide selection of outside reading options relating to the topic of Black History, with titles such as The Color Purple, Beloved, Fredrick Douglass’s My Escape from Slavery and Howard Zinn’s On Race.

Overall, the collection does a great job of honoring, remembering, and respecting the struggle of African Americans. The podcasts will keep listeners engaged for days and the interviews give historians hours of first-hand accounts.

Overall, the collection does a great job of honoring, remembering, and respecting the struggle of African Americans. The podcasts will keep listeners engaged for days and the interviews give historians hours of first-hand accounts.

If you enjoy these iTunes U collections, be sure to check out our own podcast, 15 Minute History

And explore the latest finds in the NEW ARCHIVE:

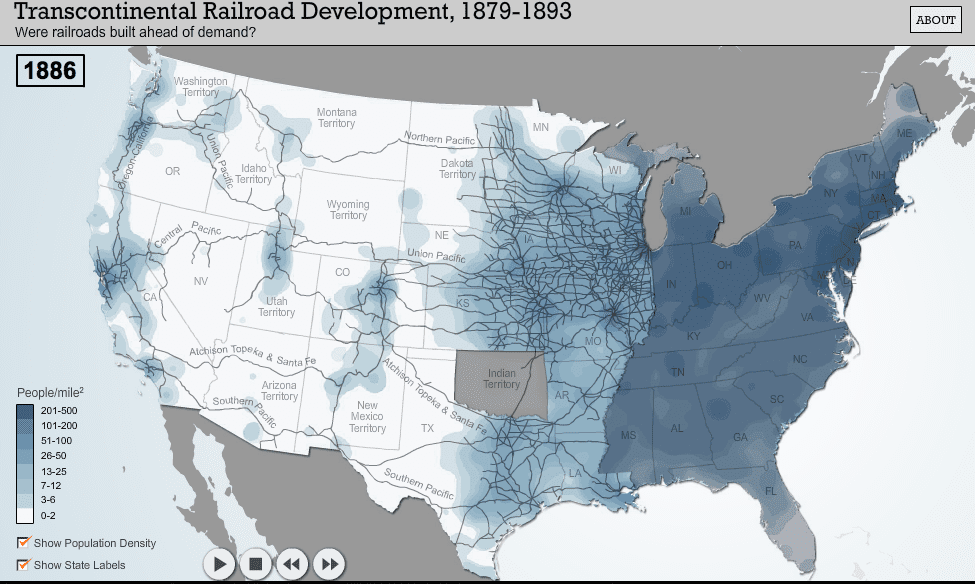

Maps and primary documents that change before your very eyes

Photo Credits:

Screenshot of the iTunes U podcasts and books being featured for Black History History Month

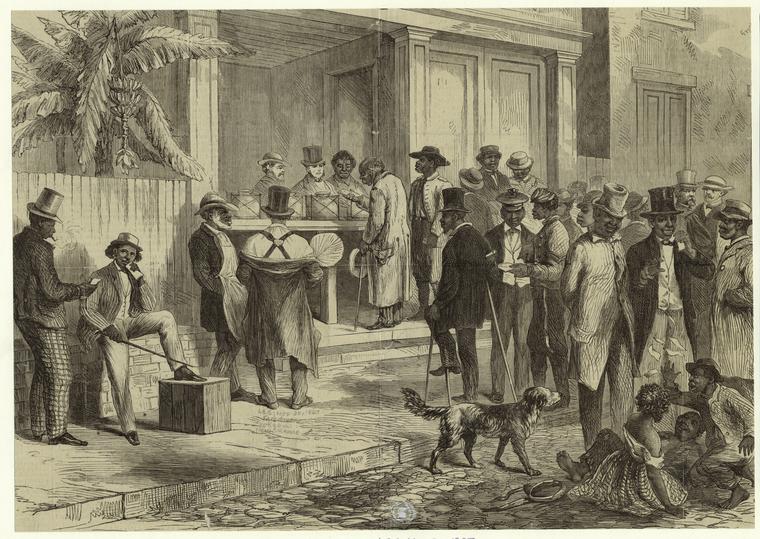

1867 engraving of African American freedmen in New Orleans voting for the first time (Image courtesy of New York Public Library Digital Collection)

Participants in the 1965 civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

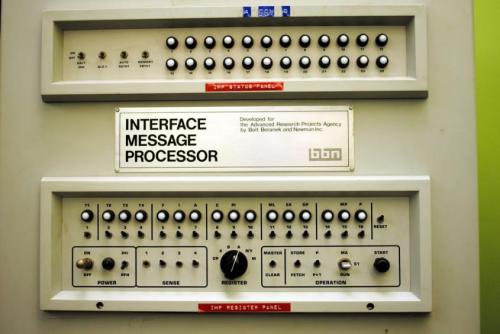

bibliographies, I conducted further research to locate copies of primary materials. I also contacted the authors for interviews and the resultant discussions would further guide my research in new directions. I was able to locate the Center for the History of Physics’ Neils Bohr Library website and its oral histories, the Computer History Museum’s Corporate Histories Collection and its numerous assorted documents, and the numerous historical films released by the American Telephone and Telegraph Corporation Archives. I accessed numerous research databases, primarily JSTOR, IEEEXplore and EBSCO Academic Complete. I contacted alumni from semiconductor firms and obtained further perspective on the industry. These discussions would lead to a final round of research at the libraries of the University of Texas at Austin and the J.J. Pickle Research Campus.”

bibliographies, I conducted further research to locate copies of primary materials. I also contacted the authors for interviews and the resultant discussions would further guide my research in new directions. I was able to locate the Center for the History of Physics’ Neils Bohr Library website and its oral histories, the Computer History Museum’s Corporate Histories Collection and its numerous assorted documents, and the numerous historical films released by the American Telephone and Telegraph Corporation Archives. I accessed numerous research databases, primarily JSTOR, IEEEXplore and EBSCO Academic Complete. I contacted alumni from semiconductor firms and obtained further perspective on the industry. These discussions would lead to a final round of research at the libraries of the University of Texas at Austin and the J.J. Pickle Research Campus.”