In The Forgotten Armies: The Fall of British Asia, 1941-1945, Christopher Bayly and Tim Harper chronicle the war years of the British Empire in its Asian Crescent, which curved from Calcutta to Singapore into Malaysia and Burma. Soldiers from the British 14th army stationed in India and Burma felt that few in the West took notice of them and sardonically called themselves the “forgotten army.” This label remains pertinent even today as the battles in Europe loom larger in the histories of the WWII than the war against Japan in Southeast Asia.

The “forgotten armies,” however, include much more than Britain’s 14th army. The forgotten armies encompass Subhas Bose’s Indian National Army, which fought for India’s liberation on the Japanese side, the Burma Independence Army of Aung San, and Chin Peng’s communist guerilla army in Malaya. Furthermore, Bayly and Harper’s forgotten armies also include the some 600,000 refugees who fled Burma in 1942 and perished in the mud and “green hell’ passes of Assam, as well as the thousands of laborers who toiled building the Burma – Thailand railway. Finally, this book’s forgotten armies include the Indian coolies, tea states workers, tribal people, ‘comfort women,’ and the nurses and doctors who provided Japanese and British soldiers with much needed labor and assistance. In this book, Bayly and Harper “reassemble and reunite the different, often unfamiliar narratives,” of the Far Eastern War, but the book amounts to much more than a military history of the Japanese invasion of the British Asia. The authors draw a “panoramic picture” of a region ravaged by “warfare, nationalist insurgency, disease and famine,” during the five daunting years from 1941 to 1945. Furthermore in the concluding pages, the authors argue that Japanese occupation hastened nationalist struggles for independence in the region.

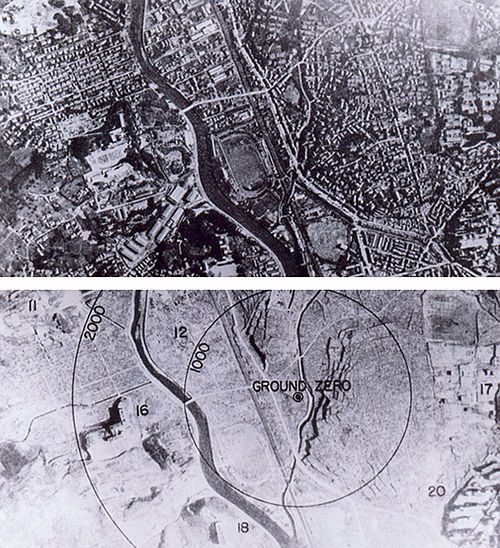

Workers with hand tools build the Burma Road in southwest China, 1944

Workers with hand tools build the Burma Road in southwest China, 1944

In The Forgotten Armies, Bayly and Harper present an exemplary scholarly work that draws from a large number of memoirs and diaries. But the authors deserve most praise because, in addition to scholarly accuracy and scope, they offer the nuance, enticement, and that feeling, which we can only call human touch, of great fiction. Take, for instance, Bayly and Harper’s description of the plight of refugees who fled from Burma into India: “Women and children collapsed and drowned in the mud […] Porters refused to touch the corpses so they lay decomposing until medical staff arrived with kerosene to burn them. The butterflies in Assam that year were the most beautiful on the record. They added to the sense of macabre as they flitted amongst the corpses.” Passages like this one stir a multitude of emotions: from shock, to terror, to anger, to sorrow and, finally, compassion. The authors paint a vivid and memorable picture of Malaysia and Burma under Japanese occupation and of India mobilized for war, and they tell a heart-wrenching and gripping tale of suffering and despair, a tale that the reader will feel both glad and sad to know. Bayly and Harper bring to life the many ‘forgotten armies’ that fought in Southeast Asia during WWII so that we never forget them again.

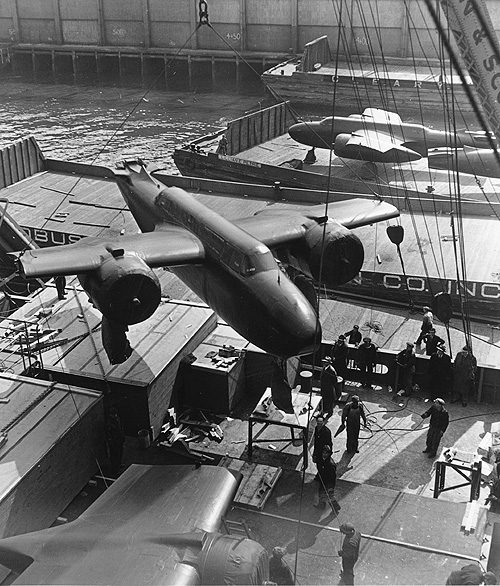

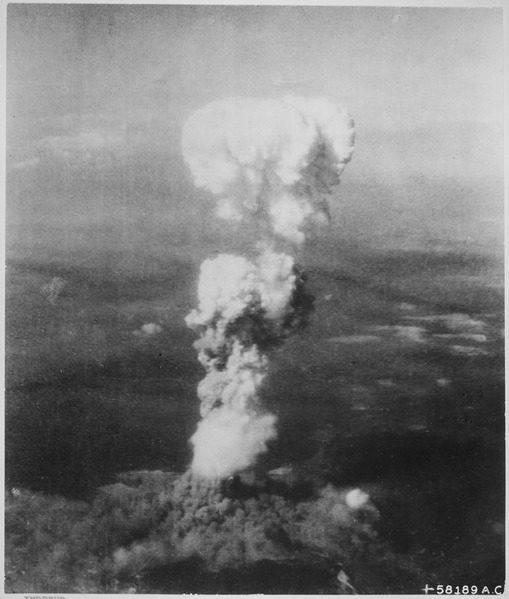

Photo Credit, US Army Signal Corps, via Wikimedia Commons

by

by

by

by

by

by