“They did it. Not us!” According to historian Tony Judt, this was the way Europeans tried coming to terms with the fate suffered by their Jewish neighbors during the Second World War. Pointing their fingers at the Germans, other Europeans chose to repress the memory of widespread participation or acquiescence in the persecution of Europe’s Jews. The role of ordinary people in betraying their Jewish neighbors, often in the hope of material rewards, appears in survivor testimonies and was remembered by families and communities as the war came to an end. Nevertheless, this knowledge was suppressed in the name of reconstruction, a process of social, political, and moral reconstitution after years of occupation and war. It took a generation before historians, writers, filmmakers, and other voices began questioning this public memory of the Second World War. In Germany, the Auschwitz Trial (1963-1965) confronted Germans with the Nazi past, and in France, the documentary The Sorrow and the Pity (1969) created a storm of controversy and helped break the taboo surrounding collaboration with Nazi rule. In communist Eastern Europe, the 1960s witnessed similar challenges to popular memories by writers, artists, and other activists.

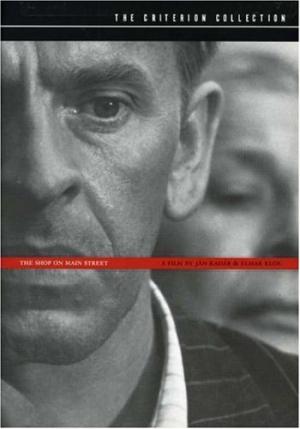

The Academy Award-winning, The Shop on Main Street was one of a series of Czechoslovakian films that looked critically at the participation of regular people in the Holocaust. Set in a small town in Slovakia, at the time a Nazi puppet state, the film suggests that ordinary men and women were deeply involved in the destruction of Jewish lives. In difficult conditions, good people do bad things; this is the tragic story of just such a person.

In 1942, Tono Brtko, an underemployed carpenter, embarks on his ‘career’ as an Aryanizer, the non-Jewish manager of a store belonging to the elderly, Jewish widow Rozalie Lautmann, played by the famous Yiddish actress Idá Kaminská. Driven by an ambitious, domineering wife and his own desire for greater status, Tono becomes a mild-mannered oppressor, but his affection for Mrs Lautmann grows. Unable to comprehend the new moral order and hence Tono’s real business in her shop, she embraces what she believes to be a new, helpful assistant as a long-gone son. Kaminská and Josef Kroner as Tono give us complex, powerful, and deeply touching performances. The film brilliantly investigates the ways people became morally and materially invested in the removal of Jews, the blurred boundary between bystander and perpetrator in moments of persecution, and the fragility of love and courage in times of fear. Although the filmmakers invited audiences to reflect on the limits of personal responsibility in Communist Czechoslovakia, The Shop on Main Street raised questions that we continue to ask ourselves today: Why do ordinary people become participants in the persecution and murder of their neighbors?

You may also like:

David Crew, Normal Pictures in Abnormal Times

A List of Films about the Holocaust

For more on Czech Jews, you can read Hillel Kieval, Languages of Community: The Jewish Experience in the Czech Lands

By

By