You cannot find the Muscogee Nation in most state-standardized social studies curricula. Take it from an educator who taught high school history in Buffalo, NY for seven years. The sovereign nation, which recently dropped the settler-dubbed “Creek” from its official title, is one of the largest in the country, with a membership of nearly 90,000.[1] The Muscogee controlled millions of acres in what is now Georgia, Alabama, and Florida, built staggering earthen pyramids, adopted a constitution, and produced Poet Laureate Joy Harjo .[2] Yet in most schools, they have been rendered virtually invisible.

Of all state curricula, New York state educational materials come closest to mentioning the Muscogee, and only by inference: “Students will examine Jackson’s presidency . . . including the controversy concerning the Indian Removal Act and its implementation.”[3] The Trail of Tears is alluded to only in terms of a political “controversy,” when in fact it is one of the most egregious human rights violations to have taken place on American soil. In the state’s 9–12 social studies framework, it is cited as a post-law “implementation” instead of an act of genocide involving the forced removal of some 100,000 Indigenous people that killed 3,500 Muscogee and thousands more from Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole tribes.[4] If these war crimes are missing from the historical record and deemed non-essential to teaching history in New York State (along with any representation of post-19th century Muscogee historical life, let alone of its agency, resistance, and joy), it may not come as a surprise that the closest Texas gets to naming Muscogee people is by calling Populist-era “Indian policies” a “political issue.”[5] Georgia and Oklahoma standards detail more Indigenous history than most, but still do not name the Muscogee or the Trail of Tears.[6]

The absence of the Muscogee Confederacy from state-sanctioned educational narratives obscures a complex history of suffering but also exploitation.[7] For example, the narratives do not mention the fact that the tribes of the Muscogee Confederacy enslaved Africans and African-Americans. In fact, the Muscogee—along with the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole (known as the “Five Civilized Tribes”)—practiced slavery, bought and sold enslaved peoples, and both defended and deplored slavery’s morality alongside the rest of the nation as pre-Civil-war-era sectionalism splintered the divided house of the United States. State educational narratives also do not discuss how the violent expulsion of these five tribes from their Southeastern lands meant a westward expansion of slavery. This expansion would later fan the flames of slavery-based conflicts such as the Texas Revolution, the Mexican-American War, and the Civil War.[8]

I didn’t learn this fact until I read it in a textbook, my life-raft for content, in my first year of teaching 16 and 17 year olds U.S. history. I was stunned by the realization. How had I never been taught that some Indigenous nations participated in chattel slavery? How had my undergraduate degree, exclusively centered on how to be a U.S. historian, skipped that chapter?

Finding Rebecca McIntosh Hawkins Hagerty

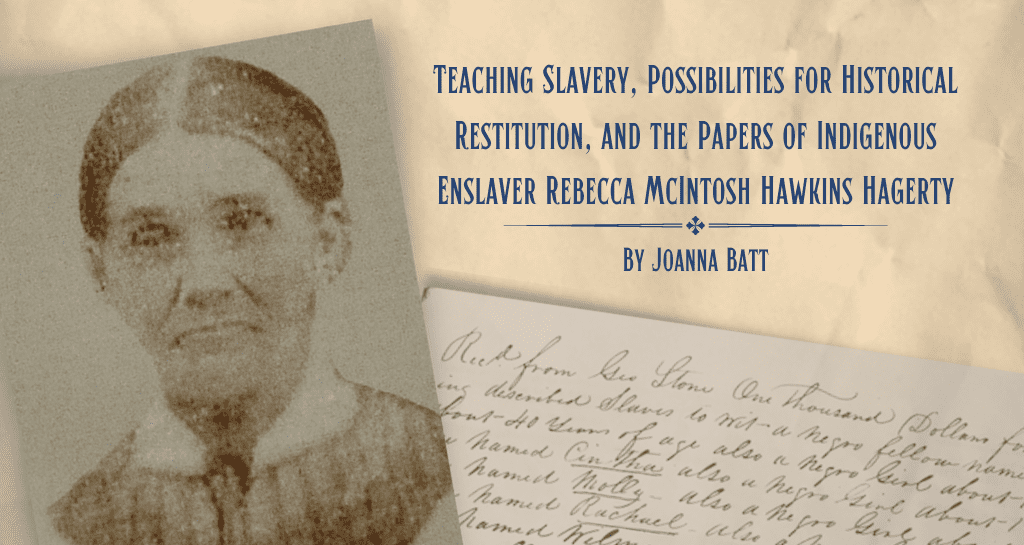

Years later, as a history educator and doctoral student, I was given a class assignment to research and transcribe a little-known document related to slavery at the Dolph Briscoe Center archives. Sifting through dusty archive files, I encountered the papers of Muscogee enslaver Rebecca McIntosh Hawkins Hagerty.

Hagerty was a three-quarters Muscogee woman who owned over 150 enslaved people. She was worth upwards of $112,000 in 1860, close to $4 million today. She died as one of the wealthiest Texans—let alone women—on Muscogee land in Oklahoma at age 73.[9] Her detailed estate inventories, as well as her frequent visits to court to advocate for land holdings as a woman, leave an extensive record of her life.

There is a rich history on Hagerty, with sources naming her as a “legendary pioneer,” bootstrap nods aplenty. But very few sources delve into the complexities, gender identity, and values of a woman who was an enslaver to hundreds of enslaved people, including fellow women with mixed ancestry who shared her Muscogee blood. Even fewer examine the complexities, genders, and human identities of the people she enslaved.

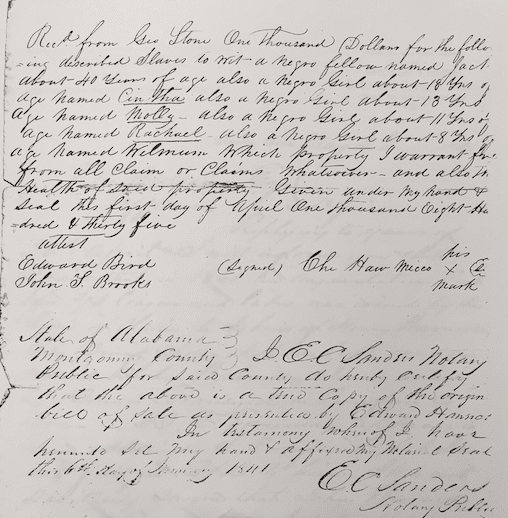

However, one document included in the Briscoe’s Hagerty papers sheds light on this complex story. It is from 1841, or rather seems to be a copy of a document from 1841 that may no longer physically exist. It is a bill of sale for enslaved persons but is not marked as so, in a folder labeled “‘Miscellaneous papers’ (Unknown, 1841).”[10] Below is my 2019 transcription of the document, which I have named Bill of Sale for Five Enslaved Persons.[11] It was signed in Alabama, Hagerty’s second husband’s birthplace and business hub.[12]

Reed. From [?] Stone One Thousand Dollars for the following described slaves to wit a negro fellow named Jack about 40 years of age also a Negro girl about 18 yrs of age named Cintha also a negro girl about 13 yrs of age named Molly – also a negro girl about 11 yrs of age named Rachael- also a negro girl about 8 yrs of age named Wilm[a] which property I warrant for from all claim or claims whatsoever – and also [the] Health of said property Given under my hand [&] seal this first day of April One thousand Eight hundred & Thirty five attest his

Edward Bird (signed) The [Haw? Micco?] x [?]

John S. Brooks Mark

State of Alabama Montgomery County I. E.C Sandend Notary

Public for Said County do hereby certify that the above is a true copy of the origin[al] bill of sale as presented by Edward Han[sict?]

In testimony where of I have hereinto [???] my hand [&] affixed my [Notarial] seal this [?] day of January 1841

E.C. Sandend

Notary Public

The document reads that a sum of $1,835.00 was paid for five humans (roughly $63,000 today). The description starts with a “negro fellow Jack, about 40 years of age,” and then the remaining four persons seem to be women. Curiously, three of the women’s names are underlined, and their ages get progressively younger, the oldest being Cintha, 18, and the youngest Wilm[a], 8. Eight years old. The rest of the document uses cold, legal language followed by a bevy of male signatures—with an x, perhaps denoting their illiteracy—for a now-notarized April 1841 dated copy of a sale that seems to have originally taken place in January of that same year.

However brief, the document irrevocably changed the lives of the five human beings listed. What would it mean to speak the names of this man and these four young women out loud? To wonder aloud in a book, or a classroom (where elementary, middle, and high school students cannot claim their ages would save them from similar treatment) just who Jack, Cintha, Molly, Rachael and Wilm[a] were? To probe the historical psyche of a Muscogee woman like Hagerty who enslaved people of both African American and Indigenous descent? Who made so much money that she ordered lobsters and brandied cherries by the barrel thanks to work from girls like Molly, age 13, and Rachael, age 11, who probably never tasted one cherry?[13]

This document complicates the Black/white binary of slavery, showing that a mixed-blood Muscogee woman enslaved people who were African American, and possibly Muscogee themselves.[14] It also troubles the dominant idea of male-only enslavers, showing that women were enslavers as well, with some like Hagerty having property rights and buying enslaved peoples, including eight-year-old girls. So much historical research of female enslaved persons focuses on the physical and sexual abuse from male enslavers. These horrific stories of sexual violence need to be told. But what of the relationships between female enslavers and female enslaved persons?[15] What of the women who bought other women and children so their own legacy and children could profit—women of color enslaving other women of color? And what of the buying and selling of people by the Cherokee, Muscogee and other Southeastern Indigenous nations, in hopes that assimilation and profit would save their way of life and land, only then to be subject to the Trail of Tears decades later?

This document complicates slavery’s dominant historical narrative, a narrative that must be complicated, mostly because it is never quite gone, never quite past. If students today actually do learn of the Trail of Tears, very few learn that thousands of enslaved Black people marched alongside their enslavers as they walked the same path from the Southeast to Oklahoma.[16] An awareness of this aspect of history should not in any way diminish our understanding of the acute and traumatic violence unleashed against Indigenous communities, or reduce our focus on the cruelty of white enslavers. Rather, we must understand how tangled the past is, and how slavery’s toxic influence extended into unexpected places.

Atoning for the Past

Last year, the Cherokee nation launched the Cherokee Freedmen History Project in an effort to atone for their past role in slavery, and to honor some 8,500 Cherokee enrolled citizens who are of Freedmen descent. These Freedmen, as the formerly enslaved, were excluded from full tribal citizenship until a 2021 Cherokee Nation Supreme Court ruling.[17] Cherokee Nation principal chief Chuck Hoskin, Jr. explained the tribal effort to acknowledge Black descendants: “The act of slavery, which was condoned by a Cherokee law, was wrong and a stain on the Cherokee Nation . . . . [A]s chief, I apologize that we did that . . . . [W]e’re taking affirmative steps to remedy that.”[18] As they take these steps, the Cherokee Nation has begun to examine their own culpability in the system of slavery and has encouraged Freedmen’s stories from family oral histories, artifacts, and other sources to be shared. They are including and centering those who were wronged as they engage in the process of remembering with an active, reparational conscience. In the nation’s current battle for historical and cultural memory, with U. S. classrooms as a central battlefield, the Cherokee Nation’s contemporary attempts to atone for their history of slavery provide an example for educators and students of how to reckon with complex, difficult history. They prove that present-day restitution and healing can be powerful acts.

As a white woman, it is not my place to weigh in on how communities of color are seeking to right any of their historical wrongs. But as an educator, I believe the current-day actions of the Cherokee Nation have much to teach us about how we can wrestle with the complicated legacies of the past. The Cherokee Nation’s response to their slavery past and the racial, gendered layers of Hagerty’s story are narratives of precious information key to understanding the historical reckonings playing out around us. The Cherokee Nation’s actions show that those who have had a hand in committing past historical violence such as slavery must de-center themselves and feature the voices and experiences of those who were oppressed in the process, even as they leave room to acknowledge the reality that there are many layers of that oppression.[19]

Yet in order to begin such work, a diversely-researched and multi-sourced history must be unearthed from archives, including documents such as Bill of Sale for Five Enslaved Persons. Doing so would bring these historical complexities into sharp relief—not just for new research, literature, and college courses, but also for K–12 curricula. This is essential—because if primary sources about Black experiences and Indigeneity are introduced in K–12 classroom settings at all, they are most likely presented separately and not in context, with a low probability that women of color and children are featured.[20] Furthermore, if colonization and slavery are taught in K–12 schools, the likelihood that they are presented as systems in connection to each other, let alone as linked to capitalist systems of whiteness still causing collective destruction, is low indeed. But documents like Bill of Sale make nuanced, primary-source anchored conversations on these themes possible, conversations that can delve into how whiteness harms BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) communities, and how such communities can harm each other because of whiteness, too.

A history like Hagerty’s, and a response like the Cherokee

Nation’s, calls upon all of us to wade into the confounding, deeply traumatic,

maddening, and messy elements of what history really is. History makes us

grieve, seethe, and feel when it

presents us with narratives of Indigenous peoples enslaving Black people, with

women of color buying and selling women who share their blood, with white

supremacy and colonization doing unthinkable things to communities, to ways of

life, and to people like Jack, Cintha, Molly, Rachael, and Wilm[a]. We have to

keep finding, listening to, teaching, and talking about these histories, over and over again, until the day comes when the

names of the enslaved are uttered just as much, if not more, than the names of

enslavers in the annals of history.

[1]David Overall, “The Muscogee Nation is dropping ‘Creek’ from its name. Here’s why,” Tulsa World, May 6, 2021, https://tulsaworld.com/news/local/the-muscogee-nation-is-dropping-creek-from-its-name-heres-why/article_3bf78738-adcc-11eb-823d-438cbdefaf21.html; Jeanette Centeno, “10 Biggest Native American Tribes Today,” March 19, 2021, https://www.powwows.com/10-biggest-native-american-tribes-today/

[2] http://www.fivecivilizedtribes.org/Muscogee-History.html; https://www.nps.gov/ocmu/learn/historyculture/the-muscogee-nation.htm

[3] New York State Grades 9-12 Social Studies Framework, pg. 36, http://www.nysed.gov/common/nysed/files/programs/curriculum-instruction/ss-framework-9-12.pdf

[4] National Park Service, “What Happened on the Trail of Tears?”, https://www.nps.gov/trte/learn/historyculture/what-happened-on-the-trail-of-tears.htm#:~:text=Between%201830%20and%201850%2C%20about,and%20on%20their%20westward%20journey

[5] Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills for Social Studies, High School, pg. 4, https://tea.texas.gov/sites/default/files/all_HS_TEKS_2ndRdg.pdf

[6] Georgia Standards of Excellence (GSE), Grade 9 – Grade 12, https://lor2.gadoe.org/gadoe/file/38de4e22-a6ad-4a1c-a19f-5a22aa9f83f3/1/Social-Studies-High-School-Georgia-Standards.pdf; Oklahoma Academic Standards, Social Studies, https://sde.ok.gov/sites/default/files/documents/files/Oklahoma%20Academic%20Standards%20for%20Social%20Studies%205.21.19.pdf

[7] Sandy Grande, Red Pedagogy: Native American Social and Political Thought (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015).

[8] “The federal government’s expulsion of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Creek (Muscogee) tribes opened the door to the rapid growth of plantation slavery across the “Deep South”. But Indian removal also pushed chattel slavery westward, setting the stage for future conflicts over the expansion of slavery.” Barbara Krauthamer, Black Slaves, Indian Masters: Slavery, Emancipation, and Citizenship in the Native American South (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 8.

[9] Hagerty was the daughter of a Muscogee mother, Susana Rowe, and a mixed Scottish-Muscogee father, William McIntosh—who was murdered by his own people for ceding Muscogee land to the U.S. government. She was then the wife of Benjamin Hawkins, who was also murdered after business with Sam Houston towards a new Muscogee settlement in Texas. She married Spire Hagerty in 1838 and went on to build a massive plantation empire, which included multiple plantations of her own and her children’s (especially after her abusive, taken-to-drink husband whom she was in the process of trying to divorce, died in 1849). Among these properties was the Phoenix Plantation, which would be sold to Mrs. Lyndon “Ladybird” Johnson’s father in 1915. It remained in their family until 2002. Most of the people Hagerty enslaved had Muscogee blood. Charles A. Steger and Patricia Adkins-Rochette, “Rebecca McIntosh Hawkins Hagerty: The Richest Woman in Texas,” https://www.bourlandcivilwar.com/RebeccaMcIntosh.htm; “Falonah Plantation, Drew Cemetery, and Refuge Plantation,” http://www.paulridenour.com/mcintosh.htm; J. N. McArthur, “Reality, and Anomaly: The Complex World of Rebecca Hagerty,” East Texas Historical Journal, 24(2) (1986); J. N. McArthur, “Hagerty, Rebecca McIntosh,” June 15, 2010, https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fhacv.

[10] Scholars may contest whether this bill of sale was actually Hagerty’s, since it does not legibly bear her name. However, its inclusion in this folder and the origin of sale in Hagerty’s home state point to multiple connections.

[11] Unknown (signed by an Edward Bird and John C. Brooks), (January 1841), Miscellaneous Papers, 1841, 1890, Rebecca McIntosh Hawkins Hagerty Papers (OCLC 23175508, Box 3U4, Folder 11), Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, Austin, Texas, United States.

[12] McArthur, “Reality, and Anomaly,” 7. Where I was unable to read the markings, I placed a question mark. Spacing and lines were imitated to appear as they did in the document.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] A notable exception that has blasted the door open on this overlooked-for-too-long section of slavery history is Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers, They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2020).

[16] Nicole Chavez, “Native Americans weren’t alone on the Trail of Tears. Enslaved Africans were, too,” https://www.cnn.com/2021/05/09/us/tulsa-massacre-native-history-alaina-roberts/index.html [17] Russell Contreras, “Cherokee Nation wants info on Black descendants linked to slavery,” Axios, February 13, 2022, https://www.axios.com/cherokee-nation-black-descendants-slavery-63b74d3b-b23b-409b-8ecc-8e5e190a051e.html; “Cherokee Nation Supreme Court issues decision that ‘by blood’ reference be stricken from Cherokee Nation Constitution,” Anadisgoi, February 22, 2021, https://anadisgoi.com/index.php/government-stories/512-cherokee-nation-supreme-court-issues-decision-that-by-blood-reference-be-stricken-from-cherokee-nation-constitution.

[18] ibid.

[19] Colonization and the oppression of Indigenous people by settlers led to Indigenous oppression of Black people via the survival-driven assimilation of colonial practices, which included slavery. In the way we talk about and teach power, it is important to keep tracing the origins of systems of oppression back and back to their deepest roots, and then pull up there the hardest. Process is also important here: accountability is essential, but who is leading the charge and how they lead it both matter. Just as the Cherokee Nation is collecting Freedman stories and (hopefully) letting them speak the loudest in their restitution efforts, the Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS) just reminded the Catholic Church that while their atonement for past boarding school atrocities is appreciated, the story belongs to Indigenous people, who need to lead investigations and have their voices—not those of the perpetrators—heard the loudest. They stated, “Churches . . . need to understand that in this process of truth and justice a basic principle is not to cause any further harm—this includes being self-serving in seeking absolution. This is a time for survivors, Tribal Nations, and Indigenous people to lead on this issue and center their own healing, so we urge extreme caution in churches reaching out to survivors, beginning healing initiatives, recording stories, or centering their perspectives and interests on this history. The churches are perpetrators in these genocidal crimes against humanity, so they should act as such in all their communications with the victims and survivors.” As quoted in Jenna Kuze’s “Tribal Leaders Weigh in on the Catholic Church’s Effort to Engage over Indian Boarding Schools,” January 12, 2022, Native News Online, https://nativenewsonline.net/sovereignty/tribal-leaders-weigh-in-on-the-catholic-church-s-effort-to-engage-over-indian-boarding-schools

[20] This is why accessible primary sources and curriculum for teaching these topics is so essential. For examples on Indigeneity and colonization, see the National Archives’ Native American Heritage Primary Sources, the Library of Congress collections on the same subject, and the Library of Congress’ blog, which includes updated boarding school primary source sets. For examples on slavery, see the Teaching Texas Slavery Project and Learning for Justice.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.