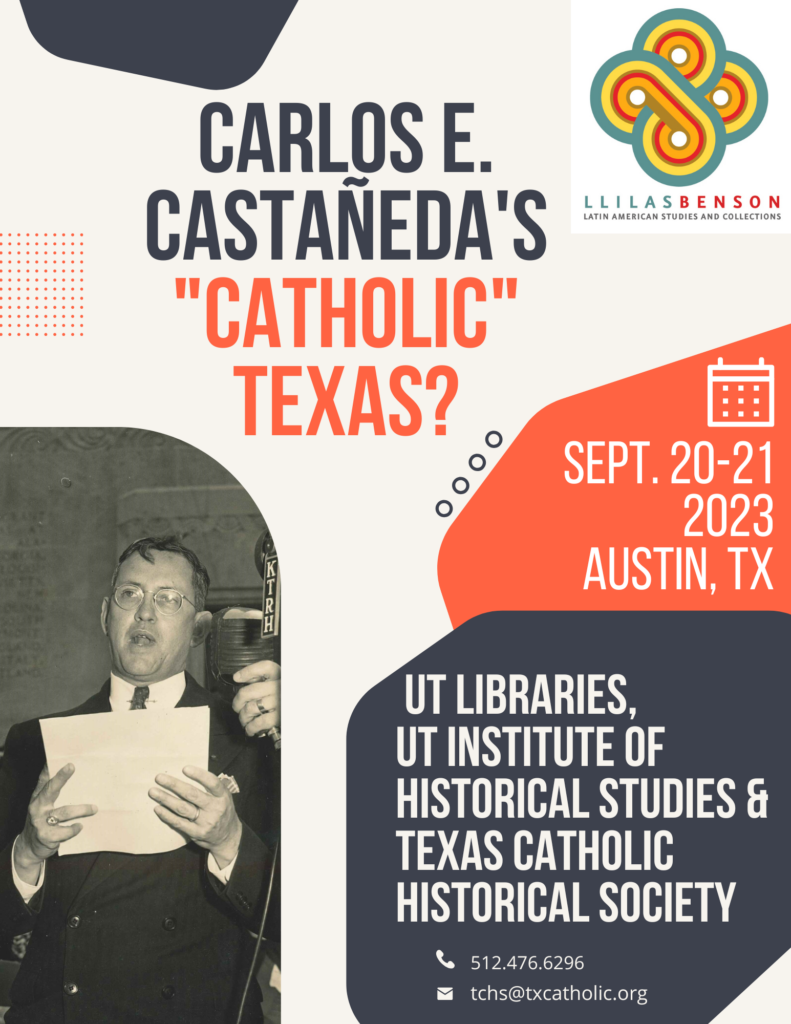

Please join UT Libraries, Texas Catholic Historical Society, The Summerlee Foundation, LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections and The Institute of Historical Studies for:

“Carlos E. Castañeda’s ‘Catholic’ Texas?”

Wed & Thu, Sep. 20-21, SRH.1, Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, Second Floor Conference Room)

Texans may remember singing the state song, “Texas, Our Texas,” during their state history classes in fourth and seventh grade. The state curriculum for fourth graders requires students to recite the words of the state song and the Pledge of Allegiance to the Texas State Flag. Texans who moved after elementary school may be more familiar with state symbols adopted by the state legislature, including the bluebonnet, longhorn, pecan tree, mockingbird, chili con carne, or monarch butterflies.

It raises an obvious question: how were the official words and symbols that represent Texas selected?

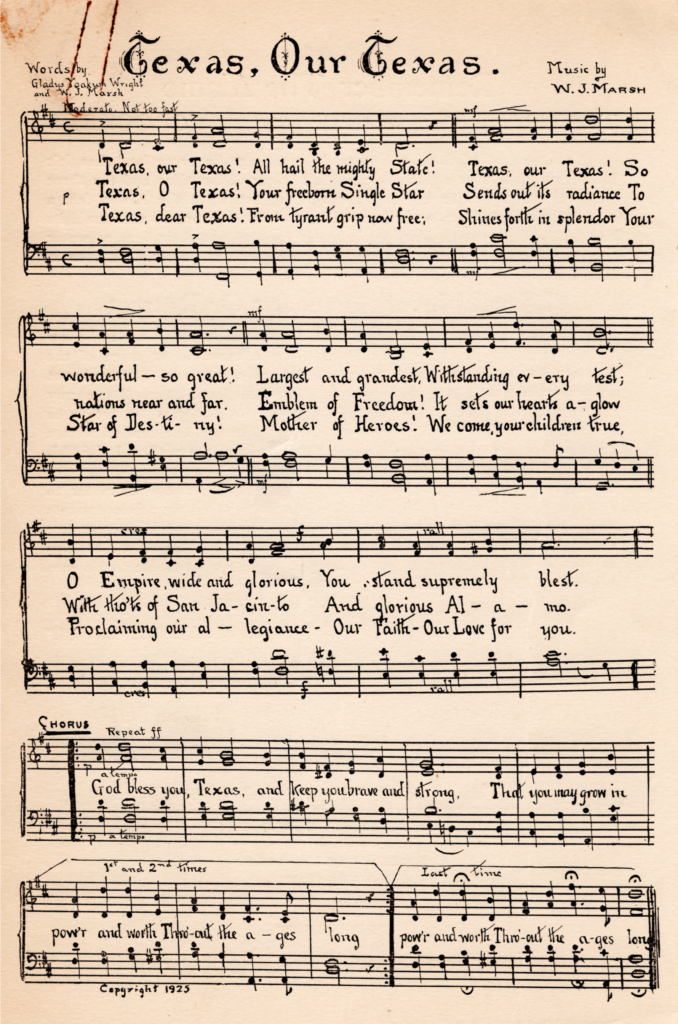

In 1923, Texas Governor Pat M. Neff announced a call for a state song through a contest with a $1,000 prize. Hopeful songwriters submitted several hundred pieces for the competition, including entries by songsmiths outside of Texas. Ultimately, “Texas, Our Texas” was selected as the winning song. Native Texan Gladys Yoakum Wright penned the song’s lyrics with music composed by newcomer William J. Marsh. Six years later, Governor Dan Moody designated the state song and officiated it during a formal ceremony in 1930. “Texas, Our Texas” remains the only official state song for the Lone Star state, with a one-word lyric change of “largest” to “boldest” following the admittance of Alaska to the United States in 1959.

Today, some debate the relevance of the state song through editorial pieces, online petitions, and private discussions. Some claim the lyrics and music composition do not accurately reflect Texas’s multicultural heritage. Others argue that songs from musical genres birthed from distinct Texana cultures, such as blues, country, rap, or Tejano, should also be recognized as official state songs. Others state that better-known songs such as “Deep in the Heart of Texas” should replace “Texas, Our Texas.”

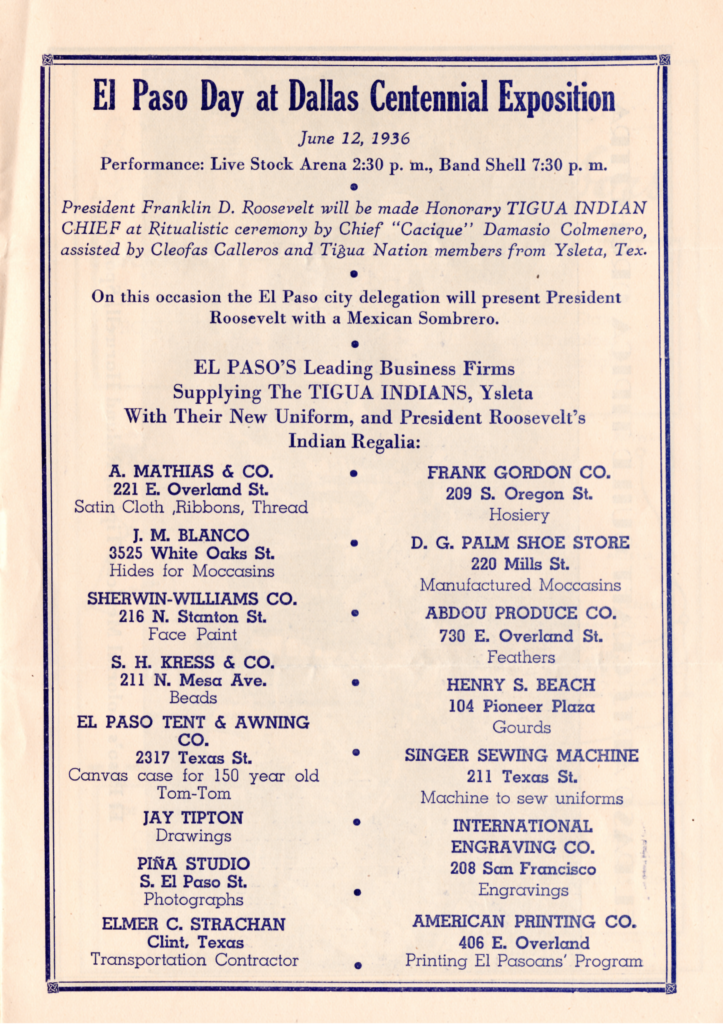

Nonetheless, the state song is part of the distinct Texas identity crafted while planning celebrations for the Texas Centennial in 1936. Beyond the centenary anniversary of the Texas Revolution’s conclusion, the Texas Centennial ushered in the adoption of unique branding used for tourism advertisements, the establishment of Texas history museums, and the erection of monuments. The Texas Centennial Exposition in Dallas showcased the state’s cultural heritage through exhibit halls and live performances. Other Texas cities hosted events showcasing their unique local history and culture.

Like the newly adopted branding romanticizing the history of Texas cities, the Catholic Church in Texas tried to cement its role within the overall Texana identity. In 1923, the same year Governor Neff called for a state song, the Texas State Council of the Knights of Columbus passed a resolution to establish their Historical Commission. The Texas Knights of Columbus Historical Commission was charged with collecting and interpreting historical documents to create a Catholic account of Texas history. The Commission proposed a publication deadline before the secular Texas Centennial with plans to host a Texas Centennial Exposition exhibit documenting Catholic contributions to the state. The legacy of the Commission’s work is seen today with its groundbreaking publication, Our Catholic Heritage in Texas, 1519-1936, which was authored by Dr. Carlos E. Castañeda.

During the 1920s and 1930s, discussions centering on identity politics questioned the nationalism of Catholics across the United States. Catholics were denied membership in social organizations or trade unions, with some Catholic institutions vandalized by the Ku Klux Klan. Nationally, anti-Catholicism prevailed during Al Smith’s failed presidential run against Herbert Hoover. In Texas, the Knights of Columbus desired to prove their Americanness through supporting historical memory projects like the Commission. Catholic contributions to statehood were not regularly as part of the academic interpretation of Texas history.

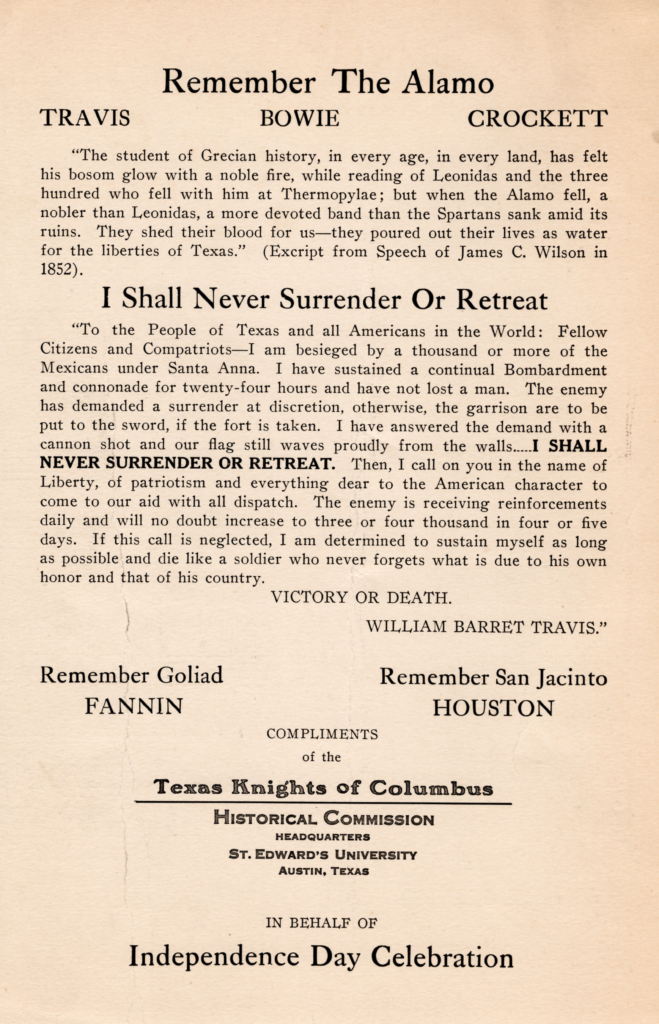

While the Commission was busy locating archival material for its final publication, its chair, Rev. Paul J. Foik, C.S.C. of St. Edward’s University, sought ways to involve lay Catholics. The Knights of Columbus and the Commission aimed to assimilate Catholics into mainstream culture by combining nationalistic symbols with public religious displays. Foik encouraged Catholic social organizations like the Catholic Daughters of the Americas, parochial schools, higher education institutions, and parish priests to celebrate Texas Independence Day as a “Catholic Fourth of July.” The Texas Independence Day celebrations were to be public patriotic events with Texas flags displayed in parishes and parochial schools.

Foik distributed the card below to use during Texas Independence Day celebrations statewide. One side of the card includes famous Texas Revolution quotes, while the other consists of the music for “Texas, Our Texas.” Although not explicitly mentioned by Foik in his correspondence, it was certainly not a coincidence that he promoted the new state anthem as its composer, Marsh, was a devout Catholic. In addition to composing the state anthem, Marsh wrote music for the Texas Centennial Exposition’s Catholic Day Mass at the Cotton Bowl Stadium with an estimated 20,000 attendance.

Explore more on the work of the Texas Knights of Columbus Commission, Dr. Carlos E. Castañeda, and the Catholic exhibit at the Texas Centennial Exposition here: https://txcatholic.omeka.net/exhibits/show/castaneda.

The conversation on the Commission and Castañeda’s legacy will continue during “Carlos E. Castañeda’s ‘Catholic’ Texas?” on September 20-21, 2023, at the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection: https://liberalarts.utexas.edu/historicalstudies/events/symposium-carlos-e-castaneda-s-catholic-texas-day-1.

Selena Aleman is the archivist for the Catholic Archives of Texas, where she oversees collections from Texas Catholic hierarchy and lay organizations like the Texas State Council of the Knights of Columbus. She holds a master’s degree in information studies from UT’s School of Information.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.