by Kody Jackson

The best stories teach us without our knowing. The best way to illustrate this, of course, is with a story. When I was in elementary school, I had to memorize the prefixes of the metric system: kilo-, hecto-, deca-, base, deci-, centi-, milli-. And I could never get it right! It always went something like this: Kilo…Hecto…something else…pass…deci…I forget…umm. All I ever wanted was to go back to feet and inches. And so it went, until our fifth grade teacher introduced us to the magical phrase, King Henry died by drinking chocolate milk. My teacher’s little jingle changed everything: King Henry made that infernal metric system memorable. It was a wonderful lesson on the power of a story, one that has stuck with me to this day.

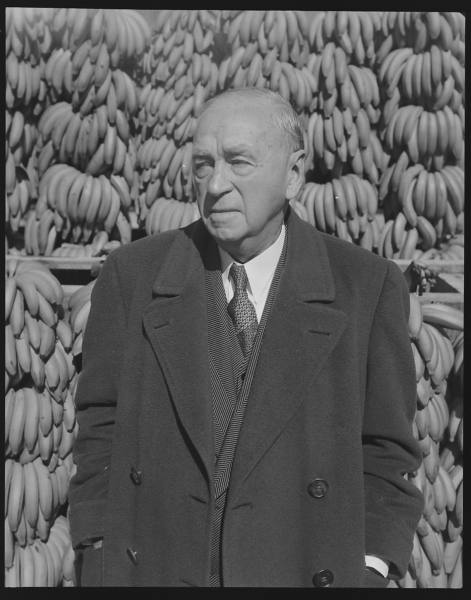

I would like to think Rich Cohen had a similar experience in his fifth grade classroom, one where he too learned how to defeat the evil metric system, but I cannot be sure. All I know is that he holds story in the same esteem in his The Fish that Ate the Whale: The Life and Times of America’s Banana King. In the first couple pages, Cohen introduces his readers to his compelling protagonist, Samuel Zemurray, a poor Jewish immigrant to the United States who later came to embody the American Dream.

The book’s first glimpse of Zemurray shows him working hard in his uncle’s Alabama grocery store, sweeping and cleaning, stacking and shelving, and always looking for an opportunity to succeed. His real break comes when a banana peddler arrives in town. Fascinated by the sight, Zemurray sets out to involve himself in the trade. He begins selling freckled bananas, the ones thought too ripe for long-distance transport. He finds a partner; they invest in a company. They purchase banana ships. Zemurray takes sole control, buys banana land in Honduras, and profits enormously. The story reaches its climax when Zemurray ascends to the presidency of the United Fruit Company, one of the United States’ most dominant and successful monopolies of the late nineteenth century. Even from this perch, Zemurray still embodies the underdog, fighting to maintain his banana empire, championing the noble cause of Zionism, and struggling to be accepted by mainstream America. The story ends as a triumph that, while acknowledging certain mistakes, largely celebrating the life of Zemurray. He was a self-made man, a shrewd banana tycoon, and, most importantly to Cohen, a Jew who succeeded in a hostile and prejudiced world.

Cohen’s story, on the whole, proves successful. As a reader, one becomes so engrossed by Zemurray and his work ethic that one almost does not notice the technical descriptions of banana planting, the history lesson on U.S. trust-busting, or the explanations of Central American politics. These chapters pass like clouds on a windy day, quickly and without much notice. Thus, in terms of story, Cohen presents his readers with a tour de force.

Samuel Zemurray, the Russian immigrant who rose to become a giant in the American fruit industry (Image courtesy of Peter Ubel)

Stories, however, are never without their faults. To accommodate his narrative structure, Cohen simplifies and whitewashes the actions of Zemurray and his fellow banana titans. Rarely do abuse and corruption come up; even when they do, they are largely minimized. In sum, Cohen tells a story of business decisions and individual effort, not exploitation and collective sacrifice. Cohen falls most grievously into this trap when writing about Zemurray’s involvement in a Honduran coup. With colorful mercenaries and crafty strategy, it starts to look more like a Wild West adventure than a violation of sovereignty. Cohen gets so caught up in the romance that he forgets the other side of the story. To neglect the Central American experience is like telling the Illiad without mentioning Priam’s grief or recounting the Crusades without mentioning the experiences of Muslims (or Byzantines, for that matter). A more circumspect tale might have noted that triumphs for U.S. business, at least in this age, often played out as tragedies for a foreign people.

While The Fish that Ate the Whale oversimplifies the complex and glorifies the morally questionable, readers should evaluate it for what it truly is, a wonderful story. Its quick pace and well-crafted characters make it exciting to read. More than that, Cohen makes the history memorable, which is no small feat. As such, it provides a great introduction to Central American history and a jumping off point for future research into the area.