By Jeremi Suri

The U.S. presidency is the most powerful office in the world, but it is set up to fail. And the power is the problem. Beginning as a small and uncertain position within a large and sprawling democracy, the presidency has grown over two centuries into a towering central command for global decisions about war, economy, and justice. The president can bomb more places, spend more money, and influence more people than any other figure in history. His reach is almost boundless.

Reach does not promote desired results. Each major president has changed the world, but none has changed it as he liked. Often just the opposite. Rising power elicits demands on that power, at home and abroad, that exceed the capabilities of leaders. Rising power also inspires resistance, from jealous friends as much as determined adversaries. Dominance motivates mounting commitments, exaggerated promises, and widening distractions – “mission creep,” in its many infectious forms.

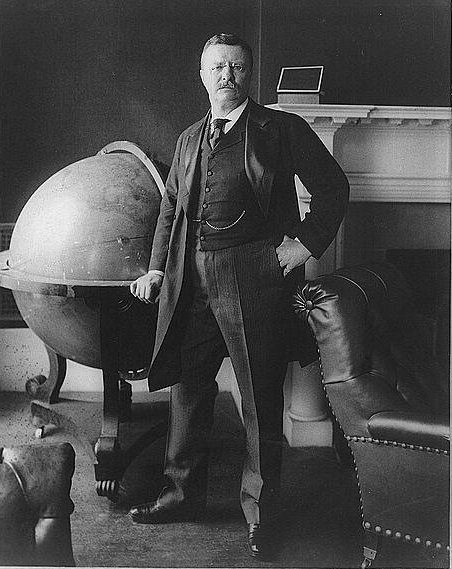

Abraham Lincoln and George B. McClellan in the general’s tent at Antietam, Maryland, October 3, 1862 (Wikimedia)

Despite their dominance, modern presidents have rarely achieved what they wanted because they have consistently overcommitted, over-promised, and overreached. They have run in too many directions at once. They have tried to achieve success too fast. They have departed from their priorities. And they have become too preoccupied with managing crises, rather than leading the country in desired directions. This was the case for presidents as diverse as Lyndon Johnson, burdened by a war in Vietnam he did not want to fight, and Ronald Reagan, distracted during his second term by the Iran-Contra Scandal.

Extraordinary power has pushed even the most ambitious presidents to become largely reactive – racing to put out the latest fire, rather than focusing on the most important goals. The crises caused by small and distant actors have frequently defined the presidents. The time and resources spent on crises have diminished the attention to matters with much greater significance for the nation as a whole. Presidents frequently lose control of their agendas because they are too busy deploying their power flagrantly, rather than targeting it selectively. This happened with Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, both of whom spent much of their presidencies fighting wars abroad that did not make the country safer.

Unmatched capabilities and ambitions encourage undisciplined decision-making, followed by stubborn efforts to make good on poor choices. These are the “sunk costs” that hang over the heads of powerful leaders determined to make sure nothing sinks, except their own presidencies. As much as they try, presidents cannot redeem the past nor control the present. Their most effective use of power is investing in future changes defined around a limited set of national economic, social, and military priorities. Priorities matter most for successful leaders, but presidents forget them in the ever-denser fog of White House decision-making.

Thomas Jefferson anticipated these circumstances two centuries ago. Although he valued virtue and strength in leaders, Jefferson recognized that these qualities were potential sources of despotism as much as democracy. The virtuous and the strong often try to do too much and they adopt tyrannical practices in pursuit of worthy, now corrupted, purposes. Machiavelli’s prince, who promotes the public good through ruthless policies, was a warning for eighteenth century American readers against centralized power run amok.

Like other founders steeped in the history of empires, Jefferson wanted to insure that the United States remained a republic with restrained, modest, and cautious leaders. He envisioned a president who embodied wisdom above all – a philosopher president more than a warrior president or a businessman president. For Jefferson, the essential qualities of leadership came from the intellect of the man who occupied the office.

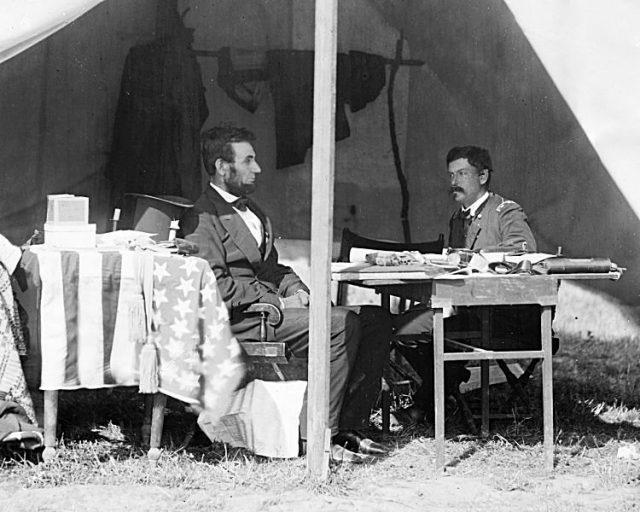

Franklin D. Roosevelt giving the State of the Union speech that came to be called the Four Freedoms Speech, January 6, 1941 (The Four Freedoms).

The checks and balances in the U.S. Constitution divided power to prevent presidential tyranny, but they did not guarantee the election of presidents with intellect, prudence, or personal restraint. Fragmented authority could be just as flagrant and misguided as centralized authority and it could franchise its despotism in multiplying offices and agencies with similar effects to the dictatorial prince. According to Jefferson, powerful democracy ultimately required wisdom and self-denial in its leaders, more than constitutional barriers. Democratic leaders had to remain introspective and ascetic as their country grew more dynamic and prosperous.

Writing on the eve of the country’s first burst of expansion, Jefferson warned that the nation’s leaders may one day “shake a rod over the heads of all, which may make the stoutest of them tremble.” Restrained use of power and disciplined focus on the national interest were the only antidotes to excess, despotism, and decline. “I hope our wisdom will grow with our power,” Jefferson wrote, “and teach us that the less we use our power the greater it will be.”[1]

Jefferson’s heirs did not heed his words. By the mid-twentieth century the rapid growth of American power made frequent misuse unavoidable and effective leadership nearly unattainable. The United States strayed from its democratic values more than any elected president could correct, despite repeated public hopes for a savior. Leaders pursued goals – for wealth, influence, and security – that undermined the democracy they aimed to preserve. Too often they sacrificed democratic procedures – supporting dictators abroad and increasing secrecy at home – for these other goals.

The widening gap between power and values produced President Donald Trump, elected to promote raw power above all. He is the final fall of the founders’ presidency – the absolute antithesis of what they expected for the office. President Trump was not inevitable, but the rise and fall of America’s highest office had a historical logic that explains the current moment, and how we might move forward.

![]()

For more on the presidency and its challenges see Jeremi Suri’s new book:

The Impossible Presidency: The Rise and Fall of America’s Highest Office (2017)

Or watch him talk about it on C-SPAN.

Or listen to our interview with Prof Suri on our podcast, 15 Minute History

Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., The Imperial Presidency (1973). This enormously popular book, written during Richard Nixon’s presidency, explained the modern growth of the presidency. The Impossible Presidency builds on Schlesinger’s insights, but argues that the growth of the presidency has undermined the effectiveness of the office.

Richard Neustadt, Presidential Power: The Politics of Leadership (1960). This is the classic treatise on presidential power, read by John F. Kennedy and every serious scholar of the presidency since then. Neustadt shows how presidential power is contingent and dependent on bargaining with other power centers. The Impossible Presidency builds on Neustadt’s insights, and applies them to the deeper historical record, as well as the present.

Erica Benner, Be Like the Fox: Machiavelli in His World (2017). Benner offers a wonderful account of Machiavelli’s life, his writings, and his influence on modern perceptions of executive power. This is a fun and inspiring read.

James M. McPherson, Tried by War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief (2008). A learned and beautifully written account of how Lincoln and the Civil War created modern conceptions of leadership.

Alonzo Hamby, Man of Destiny: FDR and the Making of the American Century (2015). A deeply researched and engaging biography of the last great American president.

[1] Thomas Jefferson to Thomas Leiper, 12 June 1815, in The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Retirement Series, vol. 8, 1 October 1814 to 31 August 1815, ed. J. Jefferson Looney (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011), 531–34.