Historian Annette Gordon-Reed often describes slavery studies as the “crown jewel of American historiography.” For Gordon-Reed and others, the historical scholarship on slavery that has emerged over the past sixty years has provided a far more nuanced and complex understanding of America’s “peculiar institution” and of American history as a whole. Much of what we now understand about slavery and its central characters has largely resulted from the diligence, resourcefulness, and dedication of historians  determined to demystify perhaps the central episode in this nation’s history. Yet, historians have not labored alone.

determined to demystify perhaps the central episode in this nation’s history. Yet, historians have not labored alone.

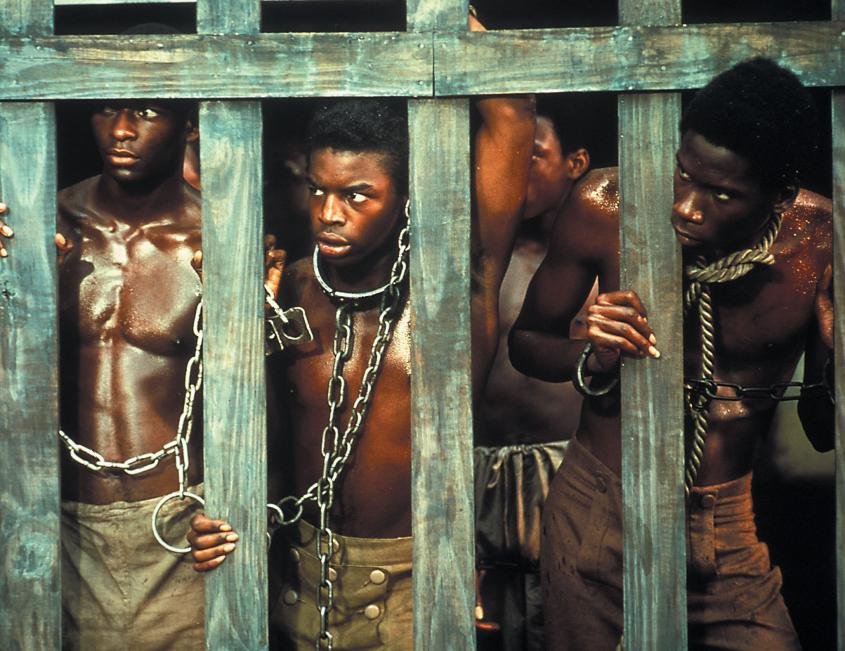

The challenge of informing an inquisitive American public about the nation’s own two-hundred year old tragedy—slavery—has not fallen squarely on the shoulders of historians and other scholars. Artists, and particularly filmmakers, have played a central role in helping the larger public grapple with the horrors and indeed, aftershocks of human bondage. The Blaxpoitation-tinged slavery films of the early and mid-1970s unquestionably paved the way for the groundbreaking 1977 television mini-series Roots: The Saga of an American Family and a handful of subsequent slavery dramas. Roots author, Alex Haley, treated millions of American television viewers to a seven-day run of an emotionally raw and mostly well-researched dramatization of one family’s experience in slavery and freedom. It was through Roots that many Americans of all races first confronted slavery in a meaningful way. As a testament to its growing power, television, and not books, history classrooms, or even scholarly conferences, then served as the most effective medium for educating Americans about slavery. Undoubtedly, the Roots miniseries and subsequent television spinoffs not only whetted the appetites of curious publics, but these visual, dramatic renderings of slavery also generated much needed conversations about race and inequality in America. Those conversations were central to the embrace of multiculturalism in the 1970s-80s. And at the same time, the public’s response to these slavery dramas compelled many trained historians to ask even bolder and more sophisticated questions about the institution of slavery in their own work. By the 1980s, a flurry of influential and field-defining slavery studies emerged. Jacqueline Jones and Deborah Gray White, for example, exposed slavery’s sweeping impact on black women, their families, and their labor in their respective works Labor of Love, Labor of Sorrow (1985) and Ar’n’t I a Woman (1985). Explorations of so-called slave culture, questions about slave agency, and even interrogations of slavery’s connections to other age-old American institutions and values soon filled library bookshelves. The rush to know could not be stopped, and again, media was there to assist.

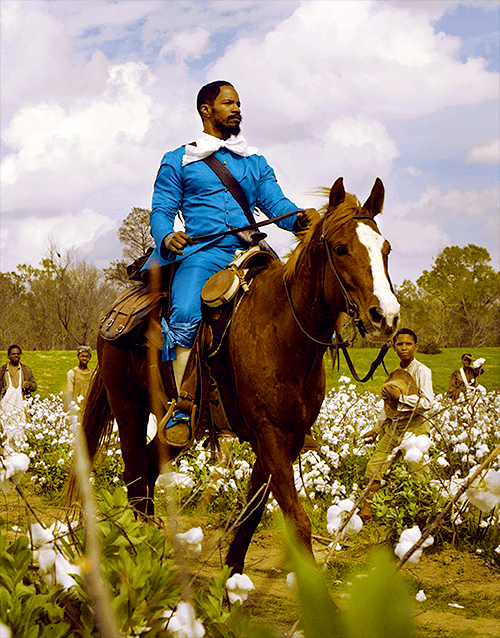

Television and cinematic portrayals of slavery often seem to thrust that sensitive topic to the fore of the public’s consciousness and in so doing, expose contemporary (mis)understandings of the institution and the era not too long past. Within the last two years, Hollywood has risked potential revenue slumps and produced two major films about slavery. Quentin Tarantino’s fictional Django Unchained exploded onto movie screens on Christmas Day 2012 with its characteristic Tarantino stamp. Though not an historical adaptation of slavery, the film garnered praise for its daring vision and originality, and on the other hand, it invited well-deserved criticism for its highly graphic display of wonton violence and its borderline comedic portrayal of the day-to-day brutality endemic to the Slave South. Django managed to get some things right about slavery, and the public devoured the so-called “spaghetti western” slavery film, but its very premise pushed the historical envelope a bit too far for many historians. In what U.S. South would one find an enslaved bounty hunter working alongside a German immigrant to capture fugitive criminals? But despite its historical absurdity, Django seems to have paved the way for what was to follow in slave genre films.

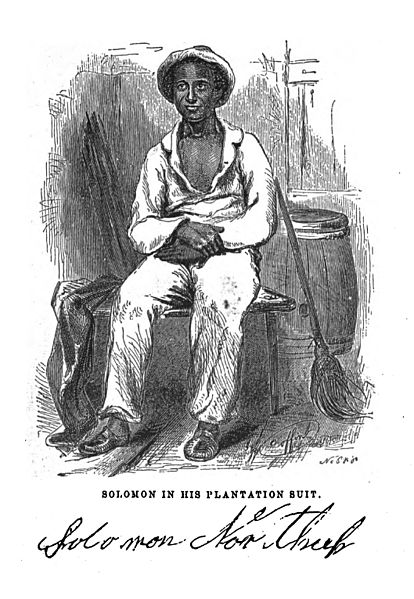

This year’s critically acclaimed Twelve Years a Slave stands in stark contrast to Django Unchained. Shaped primarily by the non-fictional 1853 memoir by Solomon Northup—a freed black man from upstate New York who falls prey to money-hungry kidnappers and is eventually enslaved for twelve years in the Deep South—this film attempts to transport viewers back into the dark and cruel world of American slavery and expose the perilous experience of quasi-freedom for freed blacks. British film director Steve McQueen brilliantly achieves this most fundamental task within minutes of the film’s opening. As Solomon Northup (Chiwetel Ejiofor) peers up and out of his dank holding cell, the viewer is immediately reminded of slavery’s most defining element—its barbarism. Not only is Northup beaten until blood stains his once crisp white shirt, he has his fundamental identity—the one thing that he truly owns, his name—beaten out of him. From this point on in the film, Northup loses his familiar and free self and becomes an enslaved man, renamed Platt. Gone, too, are his respectable black family and all of the trappings of success and respectability that his life in upstate New York afforded him. After a torturous boat ride down river, his previous free life gradually disappears into his past and a new, darker future awaits him. Furthermore, any hope that Northup had of slavery’s abolition seems crushed by his now unfortunate, spirit-crushing predicament. The former “slave without a master,” to invoke Ira Berlin’s characterization of antebellum freedmen, would now experience a similar fate endured by millions of blacks in the Slave South. Branded a slave, Platt must adapt to a brave new world. Ultimately, it is the uniqueness of Northup’s story and his liminal status that makes Twelve Years a Slave a gem of a film. And for historians, the original source material provided in Northup’s memoir remains an amazing historical find, especially for scholars of Louisiana slavery.

Using smart camera work, McQueen again capitalizes on the early minutes of the film to indict slavery as a national institution and not merely as a distinct southern problem. Herein lies the beauty and power of the film. The cinematography and imagery tell the story of American slavery and human suffering in ways that enhance the script. A whipped-slashed back, a blood-stained eye, an inconsolable mother and even Northup’s own defeated hanging body collectively provide viewers with a rudimentary, visceral education about the role of violence—both physical and psychic—in maintaining a system of human bondage and entrenching a hardened racial caste order, particularly in the American South. While screaming for help after his kidnapping, Northup gazes coldly into the gloomy Washington streets. And there, on the immediate horizon, sits an unfinished U.S. Capitol building. The now iconic statue “Freedom” had not yet found its way to the top of the Capitol dome. The irony and the symbolism of that shot, however, are profound. For right under the noses of the nation’s elite and powerful, were black men and women—entire families, or “lots”—ready to be bought, sold, or even stolen, all to fulfill the capitalist dreams of some and to assuage the racist fears of others. It is not until the Compromise of 1850 that embarrassed American politicians prohibit the domestic slave trade within the nation’s capital while simultaneously reinvigorating the system of slavery throughout the rest of the Union with the passage of a stronger Fugitive Slave Law. By this time, being a freed black in the North could have potentially posed problems for men and women like Solomon Northup, as it was not uncommon for unscrupulous slave catchers to circumvent personal liberty laws and round-up freed blacks in the North and attempt to sell them into southern slavery. Thus, the threat of enslavement for blacks knew no regional bounds; being black alone was enough. Social standing, personal connections, or even highly regarded talents were rarely sufficient protections, and certainly none of these factors mattered for Northup.

To its credit, McQueen’s Twelve Years a Slave does not shy away from the ugliness of slavery. And unlike Tarantino, he captures the disturbing physical and emotional violence inflicted on blacks by sticking to documented history rather than resorting to fantastical exaggeration. One can hardly describe the violent scenes in Twelve Years a Slave as gratuitous. Most prominently, McQueen foregrounds the very real and pervasive pattern of female sexual exploitation on southern plantations. Patsey (Lupita Nyong’o), perhaps the real breakout star of this film, endures years of rape and humiliation at the hands of the drunken Louisiana slaveholder, Mr. Epps (Michael Fassbender) and his diabolically jealous wife. Mrs. Epps (Sarah Paulson) is by far one of least likeable characters in this drama: outspoken, uncaring, self-righteous, and ruthless in her treatment of Patsey and the other slaves. The southern belle stereotype of the plantation mistress seen in so many films is thrown out the window the minute Mrs. Epps reveals her knowledge of her husband’s ongoing sexual relationship with Patsey. Though she faults her husband for this marital transgression, reminding him at one point that he is too filthy to sleep in her “holy bed,” she harbors most of her resentment and venom for the slave woman. She foolishly believes that Patsey, like so many bondwomen, had the authority to resist the illicit and unwelcomed advances of powerful white men. In one of the film’s most poignant scenes, Mrs. Epps strikes the slave woman on the side of her head with a heavy crystal decanter after she is convinced that Patsey has glared at her with contempt while she is being forced to dance in Mrs. Epps’s parlor. And it is Mrs. Epps who ultimately demands that her husband publicly punish Patsey after she wanders off without permission to a neighboring plantation, seeking soap and communion with another black woman, who is also in an equally problematic interracial ‘relationship.’ That woman, Mistress Shaw (Alfre Woodward), reveals to a much younger Patsey that she must resign herself to the unavoidable sexual predations on southern plantations. In fact, Mistress Shaw speaks candidly about her “rise” to common-law-wife status with her white husband. She tells the curious Patsey that her new position has afforded her a life far removed from the fields and the whip. Now, she lives in relative leisure and luxury, though it is clear that she has been emotionally, if not physically scarred by her messy experience with Mr. Shaw. To the filmmaker’s credit, portraying such a wide range of human relationships—across the colorline and of varying degrees of complexity—makes this film a certifiably American story, no matter how troubling.

The film’s emphasis on Patsey’s tumultuous relationship with Mr. Epps indicates McQueen’s dedication to the veracity of Northup’s memoir, and at the same time, it attests to his knowledge of scholarly studies of southern women—enslaved women and to some extent, plantation mistresses. Following the lead of historians Daina Ramey Berry, Thavolia Glymph, and Elizabeth Fox Genovese, misconceptions about southern white women in general and in particular, bondwomen’s abilities to negotiate sexual advances and handle rigorous field labor are put to rest. It is Patsey who emerges as the “queen of the fields” both in Northup’s memoir and in the film. Patsey picks more cotton than any other man or woman on the plantation, despite her rather thin frame and sex. Her skill and expertise set the standard for work on the plantation. When Patsey outpicks Northup and others, they suffer daily lashings for their inability to meet such a lofty picking goal. Thus, Patsey’s performance in the fields challenges conventional notions of skilled and unskilled labor and at the same time, forces viewers to rethink the stale, male-centered iconography of slavery. Not only were women omnipresent in slavery, they also proved to be ferocious workers right alongside some of the men.

With its adherence to Solomon Northup’s words and its obvious attention to slavery scholarship, Twelve Years a Slave succeeds in bringing the ruthlessness of slavery to film. Still, one can always ask if film has the power to present such human trauma in a most authentic and respectful manner. Or, one can ask if film is the appropriate medium for presenting slavery. Many viewers will continue to grapple with this dilemma, just as historians themselves will continue to question if their works most accurately and respectfully get at the hearts of the people, places, and times they study and the questions they ask. Just as no piece of historical scholarship is without fault, no historical film will ever “tell it like it was” or be able to convey completely what it felt like to be Solomon Northrup.

In Twelve Years a Slave, the faults are few but still worth noting. Those viewers unfamiliar with Northup’s story would be surprised to know that Northup was enslaved for twelve years. Save for the film’s name, the movie does not adequately reflect a clear linear progression of time. In fact, Northup’s agonizing twelve years on various Louisiana plantations are compressed into one long, single-note experience. Only graying hairs and a few visible wrinkles indicate the passage of time. The viewer is carried from 1841 to 1853 with very little historical context along the way; the growing abolitionist movement and raucous national political debates over slavery do not make an appearance in the film. Likewise, even the bustling city of New Orleans, with its large free black population, appeared to be an afterthought.

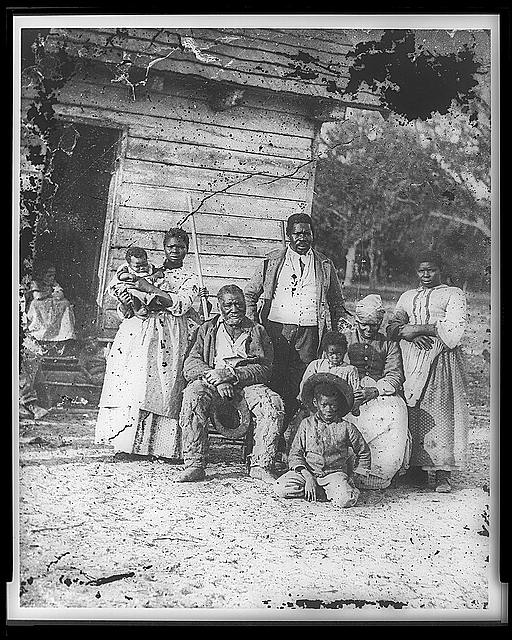

Additionally, the film could have taken more pains to recognize or even highlight the distinctive nature of sugar planting versus cotton cultivation. Historians continue to emphasize that there were many slaveries existing side-by-side throughout the South, but cotton has maintained its hold as the singular, dominant symbol of southern slavery. All southern slaves did not labor exclusively in the cotton fields. Sugar most certainly dominated the world of southern Louisiana slavery. Its unique growing conditions and labor demands unquestionably affected the nature and rhythm of slavery in that region. Men typically outnumbered women on most sugar plantations and, therefore, both labor and leisure looked markedly different from slave life on cotton plantations. The work Northup did on sugar plantations and the people he met along the way deserved more attention in the film. For example, Northup served as driver, or manager of other slaves on a sugar plantation. As a driver, he wielded the whip and capitalized on his intellect and skill to vie for greater privileges and status among the other slaves. It was also here in sugar country that Northup developed many of his closest relationships with other bondsmen and earned his Sunday money. Though he writes at length about numerous interactions and friendships with blacks and whites during his stint in slavery, in the film Northup is strangely isolated from the other slaves except Patsey,. His friendship with Mr. Bass (Brad Pitt), however, stands out, as it proves instrumental to his ultimate freedom. Surprisingly absent, though, are those homosocial bonds (close interactions between men, in this case) Northup formed with an interesting and diverse cast of male characters in sugar country. A sharper focus on this aspect of Northup’s slave experience would have added more depth to his rather flat portrayal. One thing about Northup that was abundantly clear in his memoir was his ability to adapt and make do. If anything, viewers are left wanting to know more about this side of Northup. More attention to his associations during slavery, and certainly, his life as an abolitionist once freed would have certainly rounded out the picture of this exceptional character. That story definitely warrants more attention. Yet, as is typical in some social histories of slavery, a fully developed portrait of the bondsman never truly emerges.

Ultimately, Twelve Years a Slave marks a watershed moment in slavery studies and film history in this country. While the film falls short in developing Northrup’s individual complexity, its boldness and vivid imagery in depicting fundamental experiences of slavery definitely suffice. Making historical films is a tough business and bringing a thoughtful portrayal of American slavery to big screens is especially tough. The stakes are high and the expectations are often beyond standard filmmaking requirements. Still, there is so much to learn about America’s “peculiar institution” from this film. Its warm reception might just encourage other filmmakers to continue tackling slavery and other controversial historical topics—with empathy and accuracy.

Photo Credits:

Promotional poster for Twelve Years a Slave

A scene from the 1977 miniseries, Roots: The Saga of an American Family (Image courtesy of

Tarantino’s Django Unchained (Image courtesy of Salon)

Actors Michael Fassbender and Chiwetel Ejiofor in a scene from Twelve Years a Slave (Image courtesy of Slate)

Illustration from the 1855 edition of Solomon Northup’s Twelve Years a Slave (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Lupita Nyong’o portraying the enslaved Patsey in a still from Twelve Years a Slave (Image courtesy of The Artsy Film Blog)

Enslaved African Americans hoe and plow the earth and cut piles of sweet potatoes on a South Carolina plantation, circa 1862-3 (Image courtesy of Library of Congress)

An enslaved family in Beaufort, South Carolina, 1862 (Image courtesy of Library of Congress)

Chiwetel Ejiofor and Lupita Nyong’o in a scene from Twelve Years a Slave (Image courtesy of The Artsy Film Blog)

Images used under Fair Use Guidelines

***

Further Reading:

Historical reviews of the films Lincoln and Django Unchained

UT historians reflect on the many meanings of the Emancipation Proclamation