Bby Laurie Green

100 years ago, Congress approved the 19th Amendment, which prohibited the denial or limitation of voting rights “on account of sex.”

The agonizing, fourteen-month struggle by suffragists to get three-quarters of the states to ratify the Amendment, especially its dramatic culmination in the Tennessee statehouse, has garnered much attention. But it may come as a surprise that Texas, a state that has become notorious nationwide for passing some of the most restrictive voting legislation, ratified the Amendment in just 14 days.

To be sure, Texas’s speedy ratification of the 19th Amendment represents a beacon for women’s political power in the U.S., but a critical assessment of the process it took to win it tells us far more about today’s political atmosphere and cautions us to compare the marketing of voting rights laws with their actual implications.

In a one-party state like Texas, the primaries were the elections that mattered, and 1918 marked the first time women could participate — thanks, in part, to campaigning by thousands of members of the all-white Texas Equal Suffrage Association (TESA).

Not all women got the chance to vote, however. Despite efforts by Black activists, including suffragists, Texas’s all-white primary system trumped women’s newly won right nearly everywhere in the state. Even still, the support from TESA secured the election of a pro-suffrage governor, William Hobby, and convinced him to introduce an equal suffrage amendment to the Texas constitution.

Like today, however, reactions to heightened immigration from Mexico – largely by those fleeing the violence of the Mexican Revolution – influenced Texas’s equal suffrage movement. Believing the specter of adding Mexican-born women to voter rolls would alienate legislators who would otherwise back women’s suffrage, Governor Hobby proposed a two-part amendment that would extend full suffrage to women but reverse a policy allowing foreign-born residents to vote if they had petitioned for naturalization.

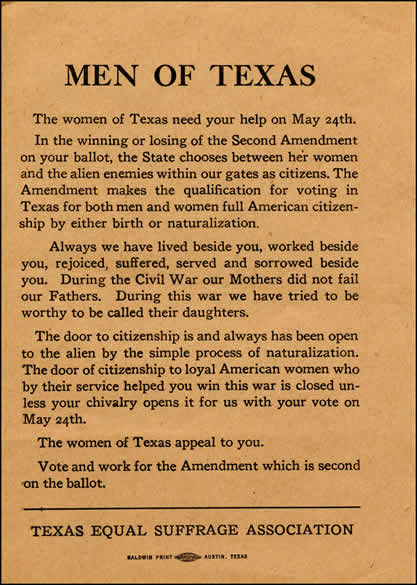

Tasked with getting voters to approve the amendment on May 24, 1919, TESA adhered to advice from national women’s suffrage leaders willing to alienate Mexican American and African American suffragists for another state win. “In the winning or losing of the Second Amendment on your ballot,” read a TESA leaflet addressed to the Men of Texas, “the State chooses between her women and the alien enemies within our gates as citizens.”

While this tactic won the allegiance of many Texans, it lost them the election — not a total surprise because immigrant men on a pathway to citizenship still retained the right to vote.

Just eleven days later, Congress approved the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, prohibiting the denial of voting rights on the basis of only sex. It took Hobby just two weeks to call a special session to approve the federal amendment’s simple language.

By 1921, Mexican-born women awaiting naturalization had lost their right to vote. In 1923, a restructured all-white primary law closed out even Black women who had managed to register earlier.

And again, on this 100th anniversary of Congress’s approval of women’s suffrage, voting rights are imperiled in Texas, this time by measures espoused as necessary to end voter fraud: the voter identification law already in place, threatened purges of voting rolls to eliminate non-citizens, and bills that nearly passed in this legislative session that would have classified registration mistakes as felonies.

In practice, these measures have targeted the same kinds of groups excluded from voting a century ago, such as the African American and immigrant women unable to reap the benefits of the 19th Amendment.

Photos of congresswomen wearing white at the 2019 State of the Union address illustrate how that history of injustices may have inspired women to figure so prominently in movements for truly universal voting rights. Those sworn in for the first time this year include many who could not have joined major suffrage organizations in 1919. But as crucial as it has been and will be to gain further political power for women by voting them into office, we can’t isolate that from burning voting rights issues today, in which Texas, like then, is a leader in voting restriction.

Laurie B. Green is an associate professor of history and a faculty affiliate in the Center for Women’s and Gender Studies at The University of Texas at Austin. Versions of this op-ed have been featured in The Houston Chronicle, San Antonio Express News, Abilene Reporter News, Amarillo Globe News, and The El Paso Times.

More by Laurie Green:

Women’s March, Like Many Before It, Struggles for Unity

The Media Matters: Reflections on the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Discovery of Hunger in the U.S.

You might also like:

Great Books on Women’s History: United States

Remembering the Tex-Son Strike: Legacies of Latina-led Labor Activism in San Antonio, Texas

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.