Originally posted on the blog of The American Prospect, January 6, 2017.

By Laurie Green

For those who believe Donald Trump’s election has further legitimized hatred and even violence, a “Women’s March on Washington” scheduled for January 21 offers an outlet to demonstrate mass solidarity across lines of race, religion, age, gender, national identity, and sexual orientation.

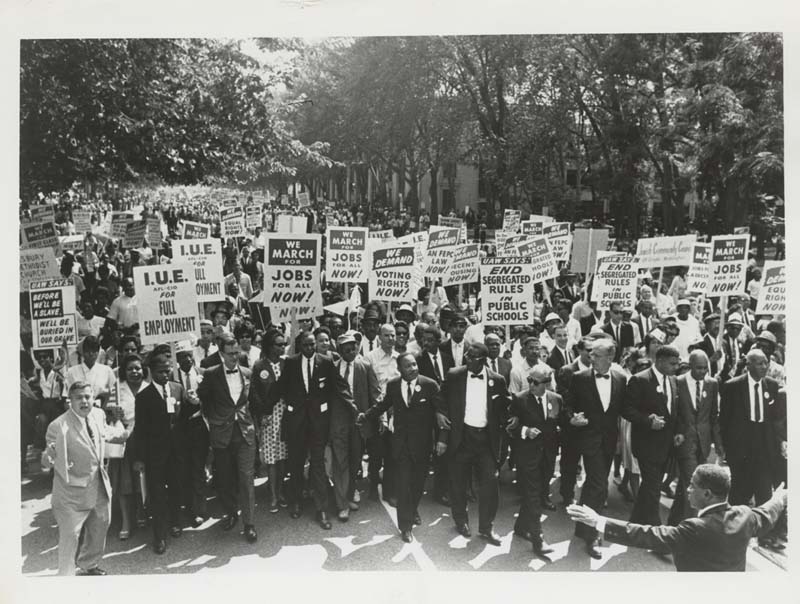

The 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (The Center for Jewish History via Flickr)

Despite its “Women’s March” moniker, the national organizing committee’s striking diversity signals an increasing emphasis on defending “human rights, dignity, and justice,” as the event’s official website states, by unifying across difference. The organizing committee includes four national co-chairwomen—Tamika Mallory, Carmen Perez, Linda Sarsour, and Bob Bland—who are African American, Latina, Palestinian American, and white, and who all have extensive backgrounds as social justice organizers and professionals with local, national, and global experience.

Linda Sarsour, Carmen Perez, and Tamika Mallory serve on the Women’s March national organizing committee (via Huffington Post).

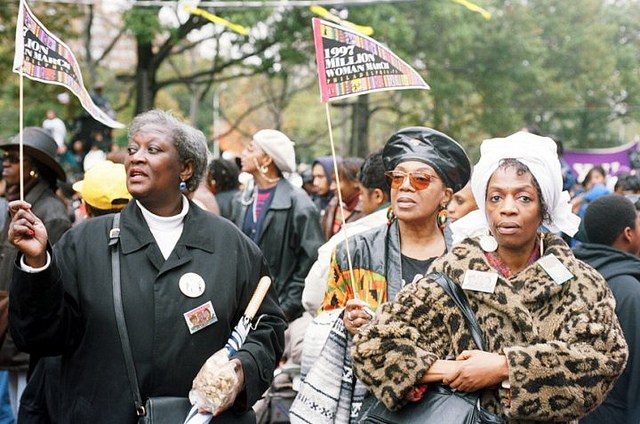

Still, neither the march, scheduled for the day after Trump’s inauguration, nor its organizers can pretend to possess perfect harmony and clarity on the direction of this nascent movement. For example, the initial organizers dropped the original moniker, the “Million Women March,” in response to criticism that it was disrespectful to African American women who had participated in a Philadelphia march by that same name in 1997. The latter had taken place two years after the iconic Million Man March. This year’s initial organizers also faced criticism that the name “March on Washington” failed to show deference to the historic role of black activists in the 1963 March on Washington, recognized as a high point of the civil rights movement. The new national committee explicitly describes its mission as one that builds on earlier movements for social justice.

Women in attendance at The Million Woman March on October 25, 1997, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (via Idealistic Ambitions).

Such internal tensions are par for the course in the history of marches on Washington, whether they involved racial justice, women’s rights, or political protest. The several thousand women who paraded down Pennsylvania Avenue in the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession, the day before President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration, were not as unified as they might have appeared. Participants included immigrant women sweatshop workers, who linked the right to vote to their movement to organize against deadly factory conditions and piecework wages. But noticeably absent from the front of the march were black women’s organizations, who supported the effort but whose participation was spurned by the militant young suffragist Alice Paul, who feared it would jeopardize support from Southern white women. These African American women ended up participating, but they were required to march behind all the other women. All the women who marched down Pennsylvania Avenue stood up to jeers and violence, but they themselves were divided by an ugly racism rooted in political pragmatism.

By contrast, some historic marches on the Capitol demonstrated racial unity against all odds. The largest convergence on Washington prior to 1963 was the 1932 Bonus Army March, which brought together World War I veterans at the height of the Great Depression. In 1924, these veterans had been honored with the promise of an old-age “bonus” redeemable in 1945. But times were desperate, and the men wanted their bonuses early. An estimated 20,000 unemployed veterans hopped freight trains, caravanned in automobiles, or walked to the capital from as far away as California, and vowed to stay put until the government delivered. Their protests placed them in a direct confrontation with President Herbert Hoover. Things came to a head on July 28, 1932, when General Douglas MacArthur ordered soldiers wielding machine guns, bayonets, and tear gas to evict the veterans from their encampment and torch their tents. The debacle, which featured news coverage of government troops attacking unarmed veterans, is thought to have helped Franklin Roosevelt beat Hoover by a landslide that November.

On the surface, the Bonus Army March may appear to have little relevance for organizers of this month’s march. But the gathering was actually a show of unity that brought together both men and women, both whites and blacks. In 1932, not only the veterans but also their wives and children poured into Washington, forming a genuine community. And despite the fact that the U.S. military had maintained racially segregated units during World War I, white and black veterans caravanned to the capital together. For two months, they and their families squeezed in beside one another as their children played between the rows of tents. They experienced MacArthur’s onslaught together, an early demonstration of racial and gender solidarity not unlike what the Women’s March expects to deliver this year.

The Bonus March was still fresh in the minds of another group of protesters, this time comprised only of African Americans, who used the threat of a mass demonstration to pressure the government for racial justice in 1941. It was the eve of the nation’s entry into World War II, and a labor organization known as the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters initiated a March on Washington Movement that threatened to bring 100,000 African American protesters to the capital on July 1 unless President Roosevelt moved to desegregate the military and order an end to racial discrimination in the burgeoning defense industry. Anxious that reports of racial injustice would damage his credibility with the Allies, Roosevelt blinked on June 25, and this march never took place. In the end, Roosevelt failed to desegregate the military; but he did prohibit discrimination by defense contractors, and established a Fair Employment Practices Committee to mediate disputes.

After Roosevelt desegregated the armed forces, Howard Perry became the first African American US Marine Corps recruit in 1942 (via Wikimedia Commons).

The role of women in this World War II–era movement holds a lesson for the women rising up to oppose Trump’s presidency today. It may be widely known that the 1941 protest was a direct precursor of the 1963 March on Washington. But less well-known is that the full, official name of black union in question, led by A. Philip Randolph, was the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Maids. The avid participation of maids, as well as of the union’s Ladies’ Auxiliary, which included porters’ wives, enabled Randolph to up his original participation projection from 10,000 in January of 1941 to 100,000 just a few months later.

Just as significantly, even though Randolph ended up canceling the demonstration, it spawned a March on Washington Movement, with chapters across the country, that persisted until 1946. Women continued as leaders in both the local and national organizations, and drew particular attention to discrimination against black females in the defense industry and other employment sectors. Women organizing this month’s demonstration at both the local and national levels are drawing on the historic organizing role of women—even those who have been forgotten—to create a lasting movement.

Anna Arnold Hedgeman (via Hamline University).

Perhaps the most famous march on Washington in the 20th century took place in August of 1963, when a quarter of a million people united to demand black civil rights. The march brought together white liberals who turned out to support African Americans, as well as Puerto Ricans, Mexican Americans, and Native Americans, in an extraordinary show of unity against racial oppression.

Nevertheless, yearly commemorations of this historic march fail to note unsettling backstories involving women leaders, whose important roles have been largely forgotten. Its top organizers, A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin, did not invite a single woman to speak, not even Rosa Parks—despite strong criticism from prominent black female civil rights advocates, including the one woman on the central organizing committee, Anna Arnold Hedgeman. Ultimately, organizers did arrange for six women, including Parks, to sit on the dais and be honored as women. But as the program shows, none of the ten keynote addresses heard that day was delivered by a woman.

Most Americans remember only one: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech. Often forgotten is the full name of the event: the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Photographs of the event show hundreds of women bearing signs calling for everything from higher wages and jobs for all to better schools and voting rights. Many are union members. Female domestic and agricultural workers, the backbone of Southern activism since the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott, also marched, at a time when federal law excluded them from minimum wages, Social Security, and from union-organizing protections.

Those photographs are testament to the role of women workers in organizing public protests. One thread running through all of these major 20th-century marches is the way civil justice issues involving race, gender, jobs, wage equity, and immigration all tended to intertwine. In the wake of the bitter election of 2016, post-election analyses have focused disproportionately on “the white blue-collar worker,” “the middle class,” or “the 1 percent.” Overlooked are the economic security and job concerns of Latina, black, and other women who toil in service, agricultural, and manufacturing jobs, at wages so low they qualify for food stamps. Such women would be devastated by the social-services restructuring proposed by GOP House Speaker Paul Ryan, of Wisconsin.

As women and men march on Washington once again, the demonstrations of 1913, 1932, 1941, and 1963 hold important lessons. The outward show of “unity” at the Woman Suffrage Procession masked its racism. The 1932 Bonus Army March speaks to the potential for diverse groups to come together in the face of extreme adversity—just as progressives are unifying today in the face of Trump. The 1941 march illustrated how organizing for a demonstration can plant the seeds for a sustained movement. And the solidarity celebrated in 1963 hid the relegation of women leaders to second-class citizenship. Ideally, the Women’s March on Washington will both avoid some of these pitfalls and help women forge new alliances that will last well beyond the event itself.

![]()

More by Laurie Green on Not Even Past:

1863 in 1963.

Women and Social Movements in the United States, 1600 – 2000.

You may also enjoy:

George Forgie discusses the work the Emancipation Proclamation left undone.

![]()