by George Forgie

There are two great legal milestones in the destruction of slavery in the United States—the Emancipation Proclamation, issued by President Lincoln on January 1, 1863, and the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, passed by Congress and ratified by the states in 1865.

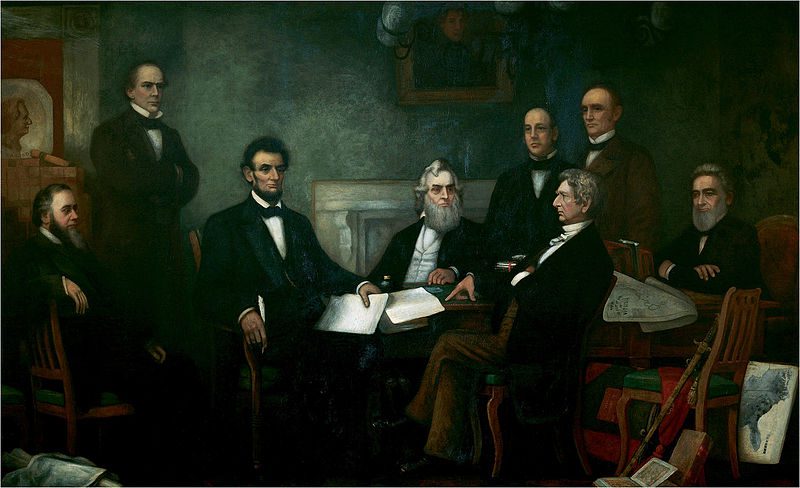

F. B. Carpenter, First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation by Abraham Lincoln

The difference between the two documents is not always well understood. Here, for instance, is how an encyclopedic website, the Internet Movie Database, summarizes the plotline of Steven Spielberg’s film, Lincoln: “As the Civil War continues to rage, America’s president . . . fights with many inside his own cabinet on the decision to emancipate the slaves.” In fact, President Lincoln had made and proclaimed his decision to free the slaves two full years before the beginning of the “fight” over the Thirteenth Amendment that is depicted in the movie. But the confusion is understandable. If Lincoln freed the slaves in 1863, why were he and his cabinet—and others—fighting about the future of slavery in 1865? The short answer is that, momentous as the Emancipation Proclamation was, its reach was limited. It promised to liberate the approximately three million slaves held in those parts of the country controlled by the Confederate rebels, but it left in bondage nearly one million slaves held in those parts of the country loyal to the Union. More crucially, the Emancipation Proclamation did not abolish the institution of slavery. Indeed, on that subject, it had not a word to say.

When it was framed in 1787, the Constitution contained provisions designed and understood to protect slavery in the United States. This was why the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison condemned and burned the document in 1854 as a “covenant with death” and “an agreement with hell.” This was why President Lincoln in his inaugural address in 1861 had no problem endorsing a proposed amendment to the Constitution explicitly barring the federal government from ever interfering with slavery in the states where the institution was legal.

Less than two years later, Lincoln interfered with slavery more than any American ever had before, by issuing the Emancipation Proclamation. His rationale was straightforward: our objective is to suppress the rebellion. We all agree that we must do everything we reasonably can to destroy the rebels’ capacity to make war. Thus we blockade their ports, we seize their military resources, and we kill their soldiers. How is taking away their labor force any different? And how better to accomplish that than to welcome the slaves to freedom?

This rationale appealed to Northerners who might have been indifferent or even hostile to freeing the slaves, but who at the same time were willing to support whatever measures were necessary to win the war. Placed on this basis, however, the Emancipation Proclamation carried with it an obvious and ominous implication: what would happen if the war reached a point where such measures were deemed no longer necessary to win it?

The imaginations of antislavery activists quickly conjured up a variety of bleak scenarios, which laid bare the greatest vulnerability of an executive proclamation: it could be easily undone. What might Lincoln do if the Confederates offered reunion in return for new guarantees for slavery? Had he not famously told Horace Greeley in 1862 that saving the Union was more important than freeing the slaves? If Lincoln should be defeated by a Democrat in the 1864 presidential election (which for a time during the campaign seemed more likely than not), might his successor revoke the Emancipation Proclamation? What complications might arise if the Supreme Court ruled the Emancipation Proclamation unconstitutional? What would ensue if the war should end with a Union victory and with hundreds of thousands of slaves not yet actually liberated? At that point, obviously, securing their freedom would no longer be necessary for Union victory.

As the war slogged on, month after dreary month, the enemies of slavery pounded home a simple message: slavery caused the war; if emancipating slaves was necessary to win it, destroying slavery was necessary to prevent its recurrence. And the only way to put the institution beyond the chance of resuscitation was to amend the Constitution, “the supreme law of the land,” to prohibit forever the ownership of one human being by another in the United States. Millions of Americans had reached this conclusion by the beginning of 1865. Whether that number would be enough is the question that sets the stage for the constitutional drama depicted in Spielberg’s film. Spoiler alert: on January 31, 1865 the Congress passed and sent to the states for ratification an amendment to the Constitution stating that “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” The next evening, speaking to a jubilant crowd gathered outside the White House, President Lincoln congratulated “the country and the whole world upon this great moral victory.” He implicitly acknowledged that no presidential proclamation could ever be what he said the amendment now was: “a King’s cure for all the evils. It winds the whole thing up.”

More on the Emancipation Proclamation on Not Even Past:

Jacqueline Jones, “The Emancipation Proclamation reaches Savannah”

Laurie Green, “1863 in 1963”

Daina Ramey Berry, “Unmixed Blessin'”? A Historian’s Thoughts on Django Unchained“

Nicholas Roland on Spielberg’s Lincoln