by Laurie Green

The time has come, Mr. President, to let those dawn-like rays of freedom, first glimpsed in 1863, fill the heavens with the noonday sunlight of complete human dignity.

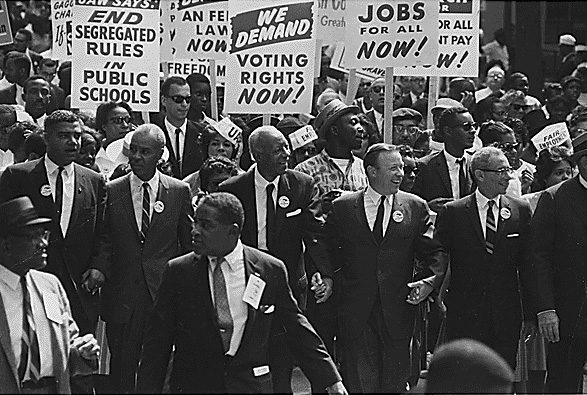

While 2013 marks the sesquicentennial of Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, this year also marks the 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington, the most famous event of the Civil Rights Movement, made so by the continual remembrance of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech. In the five decades since the March, many people have forgotten or fail to realize the tremendous meaning that the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation bore for the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s.

A shared historical memory of the unfinished nature of freedom granted by the Emancipation made these activists refer to their struggle as a Black Freedom Movement, even a Black Revolution. A century after the abolition of slavery, they were still fighting for an end to segregation and the laws that barred voting rights. At the same time, however, they also pressed for economic justice, and for dignity and respect –- in a sense recuperating the meanings of freedom that had made Emancipation signify more than the release from bondage in 1863.

During the mid-twentieth century, opponents of Jim Crow society referred directly to the legacy of slavery with language like “master-slave” and “plantation mentality” to imbue their own sense of freedom with the sense of ending long-standing, internalized beliefs about race. The Memphis sanitation workers, striking in 1968, for example, created the slogan “I AM a Man!” as a way of claiming economic justice and human dignity at the same time. Freedom was not only a negative – abolition, whether as a historical memory of the eradication of slavery or the current struggle to uproot segregation – but an indignant insistence upon human self-development.

The legendary 1963 March on Washington encompassed but was not limited to desegregation; in fact, its origins lay in the intertwined labor and civil rights movements that had powerfully emerged – not for the first time, but in a new way – on the eve of U.S. entry into World War II. In July 1941, working-class blacks led by A. Philip Randolph and others mounted a movement to march on Washington unless President Franklin Roosevelt issued an Executive Order banning discrimination in the defense industry and the armed forces. FDR did not end segregation in the military, but at the eleventh hour he ordered a ban on racial inequality in defense jobs. And yet the order only addressed wartime circumstances; the Fair Employment Practices Committee he established lasted only until the end of the war.

FDR did not end segregation in the military, but at the eleventh hour he ordered a ban on racial inequality in defense jobs. And yet the order only addressed wartime circumstances; the Fair Employment Practices Committee he established lasted only until the end of the war.

Picking up on this theme two decades later, African American labor activists including members of the newly formed Negro American Labor Council united with Dr. King to call for a March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom – a name that is commonly forgotten in commemorations of the famous 1963 event. By the time the march occurred in August, President John F. Kennedy had finally proposed civil rights legislation but organizers sought to pressure him into expanding his proposal into one that would address economic justice as well.

Randolph’s address to the massive crowd on August 28, 1963 articulated this perspective. He supported the desegregation of public facilities, but declared, “[T]hose accommodations will mean little to those who cannot afford to use them.” His speech went beyond any single demand. “We are gathered here in the largest demonstration in the history of this nation,” Randolph proclaimed. “We are the advanced guard of a massive moral revolution for jobs and freedom.” Randolph explicitly linked that moral revolution to the history of slavery: African Americans would play a vanguard role “because our ancestors were transformed from human personalities into private property.”

Even before the March on Washington, civil rights activists were forging links between the Emancipation Proclamation, the historical memory of slavery, and the Civil Rights Movement. In June 1961, one and a half years before the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, King and others began pressuring Kennedy to commemorate the upcoming centennial with a second Emancipation Proclamation. “Just as Abraham Lincoln had the vision to see almost 100 years ago that this nation could not exist half-free,” King asserted at a news conference, “the present administration must have the insight to see that today the nation cannot exist half-segregated and half-free.”

On May 17, 1962, the anniversary of the historic Supreme Court’s 1954 school desegregation ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, King submitted his appeal to Kennedy: “An Appeal To The Honorable John F. Kennedy, President of The United States for NATIONAL REDEDICATION TO THE PRINCIPLES OF THE EMANCIPATION PROCLMATION AND FOR AN EXECUTIVE ORDER PROHIBITING SEGREGATION IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.”

The document referred directly to the links between past and present:

The wells-springs of equality lie deep within our past. We believe the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation is a peculiarly appropriate time for all our citizens to rededicate themselves to those early precepts and principles of equality before the law.

Eloquently, the appeal declared:

The time has come, Mr. President, to let those dawn-like rays of freedom, first glimpsed in 1863, fill the heavens with the noonday sunlight of complete human dignity.

In the end, although Kennedy had shown initial interest in the second Emancipation Proclamation proposed by King, the President balked and the centenary passed without his seizing the moment to issue what would have been a historic, groundbreaking statement – although one sure to provoke the wrath of southern Democrats. Six months later, after violent police attacks on black youth demonstrating for desegregation in Birmingham were condemned around the world, Kennedy would call for civil rights legislation.

This is the familiar story narrated in our textbooks. The full significance of the Emancipation Proclamation to activists in the Black Freedom Movement one hundred years later has been left out of the story. Steeped in the historical memory of Emancipation and the long Black Freedom Movement, African American activists and their allies were striving to conclude a revolution they perceived as unfinished since 1863.

More on the Emancipation Proclamation on Not Even Past:George Forgie, “Work Left Undone: Emancipation is not Abolition”

Jacqueline Jones, “The Emancipation Proclamation reaches Savannah”

Daina Ramey Berry, “Unmixed Blessin'”? A Historian’s Thoughts on Django Unchained“

Nicholas Roland on Spielberg’s Lincoln

This article draws on research in:

William P. Jones, “The Unknown Origins of the March on Washington: Civil Rights Politics and the Black Working Class,” Labor: Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas 7:3 (2010): 33-52.

David W. Blight and Allison Scharfstein, “King’s Forgotten Manifesto,” New York Times, 16 May 2012.

Photo Credits:

Images of the March on Washington and A. Philip Randolph via Wikimedia Commons