Right now millions of people worldwide are reliving the American Revolution through a new historical fiction. This fictionalized revolution, however, is not televised on PBS, nor is it directed by Steven Spielberg or written by Ken Follett. Instead, this version of the Revolution comes to us through a video game called Assassin’s Creed III. Developed and published by the French gaming company Ubisoft, Assassin’s Creed III follows the story of Connor Kenway, a half-English and half-Mohawk assassin battling the British and the Knights Templar (don’t worry, I’ll explain later) during the period of the US Revolution. From Connor’s perspective, players are able to interact with famous historical figures such as George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, and explore virtual recreations of colonial cities such as Boston, New York and Philadelphia. The game, released on October 30, has already met with critical acclaim from gaming journalists and it promises to become the most consumed and financially successful historical fiction, in any medium, this year.

The video game is a relatively new medium, but it has a long record of using history to tell stories like the one found in Assassin’s Creed. Given the mass popularity of video games and gaming culture, it seems appropriate that we begin to analyze the history portrayed in this medium in the same way we consider a historical novel or period film. Why and how is history used in video games? How has this use of history changed over time? How does the use of history in video games compare to the use of history in other media? Finally, are these uses of history merely a pretense for entertainment or do they offer a real opportunity to learn about the past?

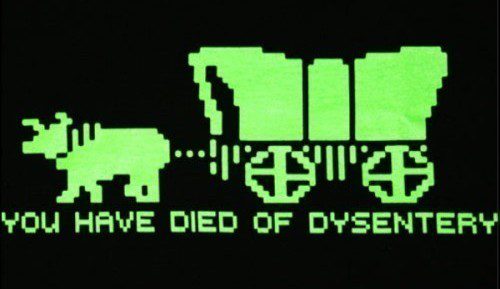

Early examples of history in video games came from titles designed explicitly for classroom use. Probably the best and most famous of these is The Oregon Trail. Developed by a group of teachers and released by the Minnesota Educational Company Consortium (MECC) in 1974, The Oregon Trail positions players as American settlers leading their families from Independence, Missouri to Oregon in 1848. While on the trail, players are required to manage their provisions as well as a number of impromptu crises, including broken wagon wheels, spoiled food, overworked oxen, and the sudden death of caravan members (usually from dysentery).Success is not guaranteed and the player’s expedition will end in failure without careful planning. Despite its rudimentary visuals and gameplay, The Oregon Trail gives players a rather accurate sense of the difficulty of transcontinental travel in the nineteenth century. It also provides players with something they cannot get from a book or film: an understanding of the past introduced through direct interaction. This interaction, however, is limited to the journey on the trail, and leaves the surrounding historical context (e.g. motivations for the journey, relations with Native Americans, etc.) up to the players, or their teacher, to fill in.

As The Oregon Trail and its imitators proliferated in classrooms during the 1980s and 90s, commercial games also began to adopt historical settings and topics. Early ventures in this genre included adaptations of historically themed board games, such as Axis and Allies, Diplomacy, and Risk, as well as digital versions of turn-based, tactical military games focused on the campaigns of the Second World War. These games were joined later by a large number of real-time strategy games (RTSs), including The Ancient Art of War, as well as games from the Total War and Age of Empires series. Like the vast majority of historical novels and films, these games focus on high politics and military history. Unlike these media, however, video games often range across long historical time periods and allow players to engage with a wide variety of subjects and events.

A key example of this type of work is the Civilization series, which debuted in 1991. Developed by the legendary Sid Meier, Civilization puts the player in charge of one of the world’s civilizations in 4000 B.C.E., with the objective of establishing and maintaining an empire until they reach either the game’s time limit (the game usually ends in the early 21st century) or one of several victory conditions (conquer all other civilizations by force, establish a colony on Alpha Centauri, be elected leader of the United Nations, or establish cultural hegemony). Players determine nearly every facet of their civilizations: agriculture, construction, demographics, diplomacy, economic policy, religion, and scientific research. The player’s civilization faces challenges from not only computer controlled competitors, but also from unhappy citizens and random natural disasters.

The Civilization series, in many respects, reflects a triumphalist, neoliberal conception of world history. Playable civilizations include crude stereotypes of current nation states, with many civilizations being completely out of place at the beginning of the game in 4000 B.C.E. For example, gamers can choose to play as the United States “civilization,” complete with an Abraham Lincoln avatar, dressed in a bearskin toga. Players often find that the game’s victory conditions are easier to achieve if they maintain a civilization that is democratic, culturally liberal, and secular. Play at all difficulty levels rewards aggressive foreign policy and the military conquest of neighboring civilizations is often a simpler path to victory than diplomatic or financial incentives. An aggressive foreign policy, however, can end in disaster if competing nations have nuclear weapons.

These problems aside, the Civilization series has much to recommend it from a historian’s perspective. It is the only history game that offers a global perspective on the past as well as an appreciation of contingency in history. The game does not follow the historical record – a player could successfully lead the Carthaginian Empire past Rome and begin the Industrial Revolution in Africa in the seventeenth century. Moreover, players can use a custom map or other modifications to create counterfactual situations in order to test variables. How different would European history be if the British Isles were connected to the continent? What if societies in the Americas had access to horses before contact with Europe? Civilization encourages players to consider the longue durée of cultural, economic, and ecological structures. And for players who seek a deeper knowledge of the game’s concepts, each edition of Civilization provides a “Civilopedia” with encyclopedia-size synopses of historical events and figures.

Though the Civilization series remains popular today, the most popular and profitable history video games of recent years come from the first-person shooter (FPS) genre. Beginning with 1992’s Wolfenstein 3D and continuing with the Call of Duty series in the 2000s, FPS games use the history of the Second World War as window dressing for what are essentially action movie simulators. Players take the role of a soldier from one of the Allied powers and shoot their way through levels filled with either German or Japanese enemy soldiers. These games make no effort to contextualize the player’s actions or to consider the moral implications of those actions. Moreover, the Second World War portrayed in these games remains firmly entrenched in the “Good War” narrative: Allied soldiers in these shooters are always heroic and righteous.

Other recent games, including the FPS series BioShock and the strategy series Command and Conquer: Red Alert, use history as the basis for adventures in counterfactuals. The first BioShock places the player in the city of Rapture, a submerged metropolis under the Atlantic Ocean built in the 1940s by a Howard Hughes-esque industrialist who hoped to create a utopian society based on Randian, or Objectivist philosophy (spoiler: it didn’t turn out so well). BioShock: Infinite, scheduled for release next year, is set in the floating city of Columbus in 1912, and will see the player engaging with Progressive Era ideas of American empire, eugenics, and exceptionalism. Command and Conquer: Red Alert begins with Albert Einstein using time travel to murder Adolf Hitler in 1924 in order to prevent the Second World War. Unfortunately, this event creates a parallel timeline in which the Soviet Union embarks on world domination during the 1950s.

The Assassin’s Creed series, which debuted in 2007, also revels in counterfactual fantasies, but attempts to place these stories in realistic historical settings. In Assassin’s Creed, players take the role of Desmond Miles, a modern day bartender who is kidnapped by a shadowy multinational corporation called Abstergo Industries. Abstergo forces Desmond to use a virtual reality machine called the Animus, which allows the user to relive the lives of their ancestors using their DNA (hold on, it gets crazier). During the first game of the series, Desmond relives the life of his ancestor Altaïr ibn-La’Ahad, a Syrian assassin who lived during the third Crusade. The second installment of the series finds Desmond reliving the life of Ezio Auditore da Firenze, a fifteenth-century Italian assassin. Eventually, Desmond learns that Abstergo is the modern incarnation of the Knights Templar and that the organization is using Desmond’s ancestral memories to search for the “Pieces of Eden,” objects of immense supernatural power (think the Ark of the Covenant in Raiders of the Lost Ark). Famous historical figures make appearances throughout the series. Assassin’s Creed II, for instance, sees Leonardo Da Vinci, act as an early modern Q to the player’s James Bond, providing the protagonist with an assortment of gadgets, including his famous tank and flying machine models.

The story in Assassin’s Creed – the Illuminati meets Ancestry.com – has much in common with the conspiratorial history seen in the fiction of Dan Brown and Neal Stephenson. This fantastical story, however, is couched in a largely accurate and detailed historical setting. The first installment of the series, set in Palestine, features period recreations of Acre, Damascus, and Jerusalem. Assassin’s Creed II, set in Italy, provides recreations of Florence, Monteriggioni, Venice, and Rome.

This game also adds historical descriptions to the buildings players encounter (and climb) while playing, including St. Mark’s Basilica, Santa Maria del Fiore, Santa Croce, and the Ponte Vecchio. A direct sequel to Assassin’s Creed II, called Assassin’s Creed: Revelations, takes place in Istanbul and provides a similar level of detail. Developer Ubisoft’s effort at recreation also extends to the human characters who populate the game world. Careful attention is paid to clothing, demeanor, and language. In pre-release coverage for the third game, creative director Alexander Hutchinson described the process of research and consulting that went into creating a Native American protagonist. Hutchison boasts of reading Wikipedia entries and watching documentaries, but his company also relies on a multinational group of professional historians and in-house researchers.

Of course, Ubisoft’s recreations are far from perfect and not always completely accurate. Yet their work demonstrates the potential for video games to provide consumers with history that is both interactive and instructive. To be sure, this history continues to focus on blood and guts, but a desire for different stories is emerging. For instance, Xav de Matos of Joystiq.com suggested last month that developers create a game focused on Harriet Tubman and the abolitionist movement. The recent growth in the popularity of video games has forced the industry and traditional gamers to begin to confront some of their biggest demons regarding racism, violence, and, most importantly, sexism. Ubisoft, for its part, published a portable game called Assassin’s Creed III: Liberation, which follows the life of a female African-French Assassin in eighteenth century New Orleans. If this trend continues, there is little doubt that new and different video game histories will emerge, and it will be exciting to see if those narratives lead to better opportunities for learning about the past.

The author would like to thank Dr. John Harney for his comments on an earlier draft of this essay.

You might also like:

Keith Stuart, “Assassin’s Creed and the Appropriation of History,” The Guardian

Here on Not Even Past: Joan Neuberger, “Telling Stories, Writing History: Novel Week on NEP.“

A free version of the original Civilization is available here

For ideas on using video games in the classroom, see Jeremiah McCall’s Gaming the Past: Using Video Games to Teach Secondary History (2011)

More by Bob Whitaker on gaming can be found on twitter @whitakeralmanac and his Playstation, Steam, and Xbox gamertag is hookem1883.

Images used under Fair Use Guidelines: See Wikipedia:Non-free content.