by Joseph Leidy

Published in 1928, the Guía Assalam del Comercio Sirio-libanés en la República Argentina, or, the “Assalam Guide to Syro-Lebanese Commerce in the Republic of Argentina,” contains tens of thousands of names and addresses for shops, services, and professionals from among or affiliated with the Syrian and Lebanese communities of Argentina. “Syro-Lebanese” here corresponds with the Spanish siriolibanés, a term that gained some popularity throughout Latin America after WWI to designate a community wherein árabe (Arab), libanés (Lebanese), and sirio (Syrian) were associated with particular political movements. It also contrasted with turco, with which Levantine migrants were (and continue to be) labelled, having initially come with Ottoman documentation.

Published in 1928, the Guía Assalam del Comercio Sirio-libanés en la República Argentina, or, the “Assalam Guide to Syro-Lebanese Commerce in the Republic of Argentina,” contains tens of thousands of names and addresses for shops, services, and professionals from among or affiliated with the Syrian and Lebanese communities of Argentina. “Syro-Lebanese” here corresponds with the Spanish siriolibanés, a term that gained some popularity throughout Latin America after WWI to designate a community wherein árabe (Arab), libanés (Lebanese), and sirio (Syrian) were associated with particular political movements. It also contrasted with turco, with which Levantine migrants were (and continue to be) labelled, having initially come with Ottoman documentation.

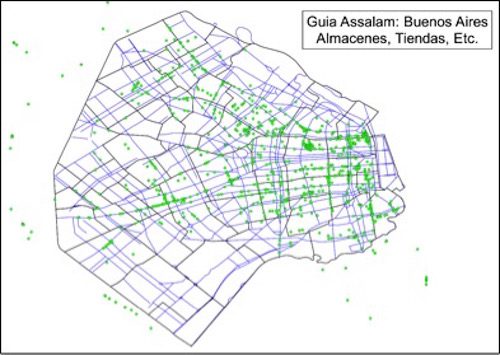

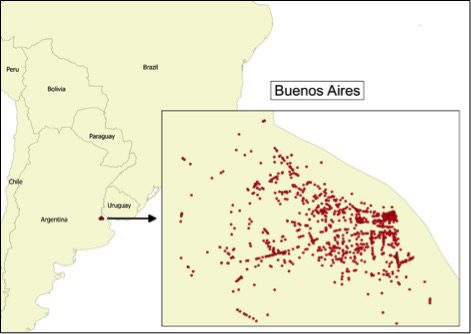

The guide features both cities with significant populations of siriolibaneses, like Buenos Aires, Santiago del Estero, and San Miguel de Tucumán, and the rural areas where many Syrians and Lebanese established themselves, including future Argentine president Carlos Menem’s father, who owned a store in the small town of Anillaco in La Rioja providence. The first map below presents the locations of the 1,633 entries for the city of Buenos Aires, providing a snapshot of the commercial and social geography of Arabic-speaking immigrants and their descendants in Argentina’s capital.

GIS data was imported from Google Maps. Some street names and numbers in Buenos Aires must have changed between the 1920s and the present, when coordinates were matched with addresses. However, these changes should not have had a major impact on this map, as most of the city’s main road infrastructure – on which the majority of the above entries are concentrated – have not changed significantly since the late nineteenth century.

A closer view with major avenues shows Syrian and Lebanese businesses throughout the city. Since the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Buenos Aires had sported a vigorous transportation network and was known as the “City of Trams.” Unsurprisingly, then, the establishments listed in the Guía could be found on and around most major thoroughfares. Concentrations, however, are evident (1) on Tucumán and Lavalle Avenues in the Balvanera neighborhood, (2) Reconquista in today’s downtown Retiro and Centro neighborhoods, and, to a lesser extent, (3) along Rivadavia in the late nineteenth century suburbs of Flores and Floresta and (4) on Patricios between the working-class neighborhoods of Barracas and La Boca.

Many Syrian and Lebanese migrants to the Western Hemisphere established themselves initially by peddling various goods to rural markets. These mercachifles, or peddlers, played an important role in bringing urban consumer goods to rural Argentina, following burgeoning railway networks and often setting up permanent storefronts. Within the urban context of Buenos Aires, Syro-Lebanese businesses also spread throughout the city to market dry goods and consumer items. Tiendas, or “stores,” in green on the map below, are around 1,000 of the 1,633 addresses listed in the Guía. The vast majority of these were also mercerías that sold sewing supplies and could be found in the city center as well as the surrounding neighborhoods. Much of the city’s population must have had access to these corner shops.

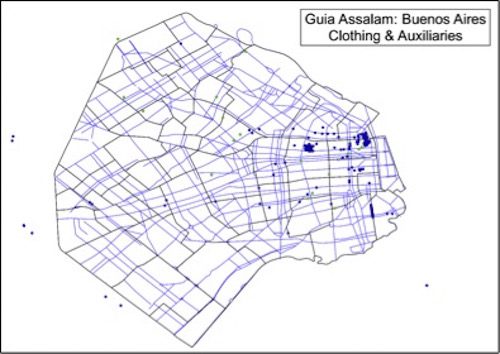

The guide also includes around 350 businesses involved in the sale of clothing products, mostly tejidos, or general textiles, in addition to specialty shops like camiserías (for shirts), sederías (silk), and artículos de punto (knit woolen clothes). These are displayed in blue below; green dots indicate auxiliary industries, such as mercerías and confecciones (alterations).

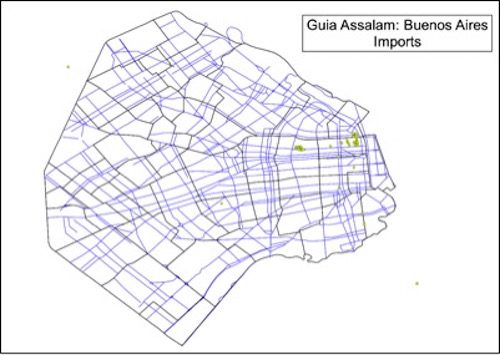

Importers, like the textile businesses, were located for the most part in two downtown neighborhoods, (1) and (2) above. For example, the advertisement for Tufik Sarquis & Hno, on Reconquista Avenue in the Centro, shows the company to have commercial connections to European textile centers Paris and Manchester and a number of registered trademarks. Import businesses are displayed below in yellow.

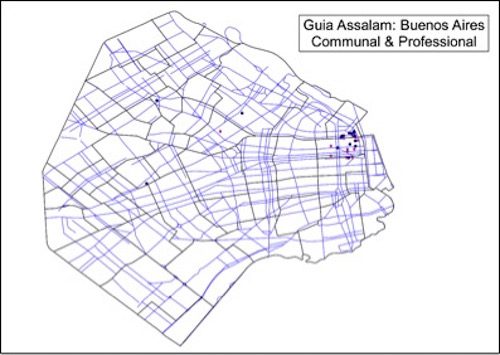

Communal institutions, such as societies, publications, and religious institutions, in addition to professionals (mainly lawyers, dentists, and doctors) generally clustered around the downtown Reconquista Avenue, where much of the siriolibanés import and textile businesses were concentrated. Here, the Syro-Lebanese elite built a public life from commercial prosperity. Communal institutions are shown below in blue, while professionals are in purple.

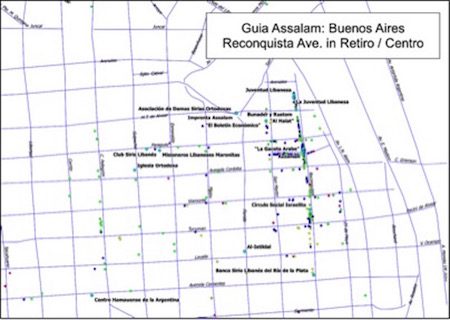

This important area, pictured in detail below, provides a portrait of the urban layout of this Syro-Lebanese public sphere. The newspaper al-Mursal was affiliated with the nearby Misioneros Libaneses Maronitas, or the Lebanese Maronite Mission, while Bunader Y Rustom published the Lebanese periodical Azzaman. On the other hand, Imprenta Assalam, in addition to publishing the guide itself, issued the periodical Assalam, while community luminary José Moisés Azize, founder of El Banco Siriolibanés and president of El Club Siriolibanés, would later issue the first daily bilingual Arabic and Spanish newspaper in Argentina, El Diario Siriolibanés.

The only communal institutions that lay outside of downtown Buenos Aires are the Sociedad Islámica de San Martín (San Martín Islamic Society), the Sociedad Siriana de Socorros Mutuos (Syriac Mutual Aid Society), and La Natura, later Natur-Islam, a newspaper with a pan-Islamic political and religious orientation. That these religious minorities among Syro-Lebanese immigrants (the majority of whom were Maronite and Greek Orthodox Christians) are peripheral in a geographical sense is mainly indicative of the smaller size and financial weight of these communities. Note, as well, the Círculo Social Israelita, or Jewish Social Circle. The Guía features many Jewish and joint Jewish-Levantine businesses; connections between merchants of both communities was likely common, especially when many Jews from the Syrian city of Aleppo migrated to Argentina in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

As a whole, the Guía Assalam gives us a sense of the social and economic structure of the Syro-Lebanese community in Buenos Aires on the eve of the Great Depression. Importation firms, communal institutions, and professional services were based in certain downtown areas of the city, while textile and dry goods stores spread throughout the urban landscape. The guide also captures the diversity of Syro-Lebanese commerce, which included Sunni Muslims, Jews, Druze and various Christian sects and their respective communal organizations. At the same time, the Guía on its own fails to provide sufficient information for the typical migration history. It lacks, for example, the birthplaces or origins of the men and women it lists, unlike an otherwise similar 1908 Syrian Business Directory from the United States. Only when paired with other sources, like censuses, would the guide tell us much about family or hometown networks and the fates of migrant businesses over time.

As a whole, the Guía Assalam gives us a sense of the social and economic structure of the Syro-Lebanese community in Buenos Aires on the eve of the Great Depression. Importation firms, communal institutions, and professional services were based in certain downtown areas of the city, while textile and dry goods stores spread throughout the urban landscape. The guide also captures the diversity of Syro-Lebanese commerce, which included Sunni Muslims, Jews, Druze and various Christian sects and their respective communal organizations. At the same time, the Guía on its own fails to provide sufficient information for the typical migration history. It lacks, for example, the birthplaces or origins of the men and women it lists, unlike an otherwise similar 1908 Syrian Business Directory from the United States. Only when paired with other sources, like censuses, would the guide tell us much about family or hometown networks and the fates of migrant businesses over time.

The Guía Assalam is, nonetheless, a fascinating document on its own merits. What prompted the creation of this “ethnic yellow pages,” and what prompts similar efforts like the Syrian-American Directory mentioned above? The answer lies in part in an effort to control and project communal reputation. The guide serves as a means for the Imprenta Assalam, the guide’s publisher, to advertise the community’s commercial reach throughout Buenos Aires and the rest of Argentina. An introduction to the guide explains the Assalam-affiliated Oficina Consultativa del Comercio Sirio, or Consultative Office of Syrian Commerce, as follows:

There are no textile trading firms that do not have hundreds of Syrians among their clientele. Being as we are the most well-suited to know the community as a whole, we are, precisely for that reason, the most consulted to provide our opinion with respect to the commercial capacity of such clients.

The Guía simultaneously displays the informational capabilities of the Oficina Consultativa and attests to the commercial success of Syro-Lebanese businesses. More than just a directory of use to other Syrians and Lebanese, then, the guide represents the positioning of Assalam and its Oficina Consultativa as a conduit for interactions between the community and the wider Argentine economy and society.

Further Readings

Theresa Alfaro-Velcamp, So far from Allah, So Close to Mexico: Middle Eastern Immigrants in Modern Mexico (2007).

Christina Civantos, Between Argentines and Arabs: Argentine Orientalism, Arab Immigrants, and the Writing of Identity (2006).

“Colectividades Siria Y Libanesa.” Buenos Aires Ciudad – Gobierno de La Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires.

Akram Fouad Khater, Inventing Home: Emigration, Gender, and the Middle Class in Lebanon, 1870-1920 (2001).

Klich, Ignacio. “Arabes, Judíos y Árabes Judíos en la Argentina de la Primera Mitad del Novecientos.” Estudios Interdisciplinarios de América Latina Y El Caribe, 1995, 109–143.

Read more by Josephy Leidy here.