Grinnell College professor Hallie Flanagan wanted to challenge and transform herself as a theatre artist. “I can’t tell you how much I feel that I need this European training if I am to do anything distinctive . . . . I want first hand knowledge of the theaters of the world . . . . In short, the year of foreign study is indispensable if I am to do work which is of power and value,” she wrote in her December 1925 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation application. Flanagan was one of many artists, not just in theater, who were heading to Europe in the 1920s to learn about innovative and sophisticated artistic practices.

Her preparation to study abroad was impeccable. She was part of the first generation of theatre artists in the US to receive specific university education in theatre practice. At Harvard University she studied with George Pierce Baker, who established theater as a serious course of study in higher education. A positive recommendation from him was the ultimate seal of approval. She was fortunate in her timing as well. Less than a generation earlier she would have had nowhere to turn to find an organization interested in funding her work.

Her preparation to study abroad was impeccable. She was part of the first generation of theatre artists in the US to receive specific university education in theatre practice. At Harvard University she studied with George Pierce Baker, who established theater as a serious course of study in higher education. A positive recommendation from him was the ultimate seal of approval. She was fortunate in her timing as well. Less than a generation earlier she would have had nowhere to turn to find an organization interested in funding her work.

The rise of the philanthropic foundation in the US is largely a twentieth-century phenomenon and one that has great bearing on the history of US theatre. The number of foundations in the US had risen from only three in 1902 to 40,000 by the end of the twentieth century. Until President Lyndon Baines Johnson approved two national endowments in 1965—for the humanities and for the arts—the American government had few resources officially dedicated to the arts or humanities. Long before President Dwight Eisenhower implemented a formal program of cultural diplomacy, private foundations had been funding US artists and scholars to study and work abroad.

There is another element of Hallie Flanagan’s story that is just as crucial as the narratives about the development of public policy and the arts, the growth of US theatre, the relationship between theatre and higher education, or twentieth century geopolitics. That element is Flanagan’s racial identity as a white woman. US theatre struggled with questions of race just as painfully as did education, government, and private enterprise. The histories of all these institutions for many years erased the contributions that people of color made to their development. White theatre leaders, who occupied most of the positions of power in US theatre, commercial and otherwise, were constantly forced to confront race as it was configured as a public issue in the moment, as well as their own prejudices, in their daily work. How they did so, as well as how their colleagues of color deployed theatre for their own means, shaped US theatre in the twentieth century. Evidence of the struggle around race, and the results of the struggle, can be seen in the ways US theatre leadership both artistic and administrative, was predominately white, except in the very few theaters run by and for people of color. Those people of color in mainstream theaters were most likely to have experiences like Rose McClendon‘s. She was a highly respected actress in the interwar years who headed the Negro Theatre Unit of the Federal Theatre Project in New York. McClendon had to have a white co-director because the FTP worried that an African American woman could not be an effective leader within the deeply segregated and discriminatory federal government.

Hallie Flanagan’s story is just one of many in the history of the remaking US theatre in the twentieth century. She was part of a large community of people, some of whom were not theatre practitioners but critics, administrators, editors, professors, or writers who assumed leadership roles in US theatre. They were neither isolationists nor exceptionalists, they believed that the US theatre should be part of the larger world, as an equal player that learns as much as it teaches. Through the interwar years and during the Cold War, this community did not lose sight of its internationalist goals or investments. Instead they worked with their counterparts around the world to ensure that theatre people of all kinds could share their work globally and that audiences could see work from other parts of the world. Their internationalism was utopian in the best sense: they saw theatre as a productive way to make the world a better place for all.

Those in the arts who pioneered internationalism did so out of frustration over the limitations of nationalism, specifically the ways it prevented people with mutual interests from working together across borders to realize common goals. Internationalists in the arts imagined a community where the bonds were as profound, defining, and affective as those of citizenship. It relied, however, on forces that sometimes resisted, sometimes affirmed, but always negotiated geopolitical identities and histories, even those that undermined their cause. Theatre people fervently believed that theatre, more than any other art form, connected people to one another and should be central to the development and expression of internationalism and the better world it envisioned.

Three crucial institutions were integral to theatre’s reinvention in the US and elsewhere during the twentieth century. They are largely without precedent; in the nineteenth century such institutions would have been unthinkable as theatre was not considered a serious endeavor deserving of serious study or geopolitical attention. The journal Theatre Arts, the American National Theatre and Academy (ANTA), and the International Theatre Institute (ITI), a NGO of UNESCO, constituted an effort to transform US theatre into a legitimate, national cultural form. They appealed to those in theatre because they supported theatre’s development and connections among theatre artists. They demonstrated to those outside theatre that the art form was a legitimate art—not mere entertainment—one with national and global reach and impact.

The Marriage Proposal, (1927),Hallie Flanagan Production

© Vassar College / Archives & Special Collections, Vassar College Libraries

The argument for theatre’s importance was not achieved solely through offstage efforts. Productions in performance too made the argument that theatre was central to education, cultural diplomacy, and the United States’ global reputation. Three particular productions exemplify how theatre was used to these ends. In 1927 Hallie Flanagan directed Anton Chekhov’s “A Marriage Proposal” performed by Vassar College undergraduates. Flanagan employed what she had learned during her Guggenheim year, particularly in Soviet Russia, to create theatre that helped her students understand themselves as part of a global artistic reinvention. The students were immersed in the ideas and methods of Russian Soviet directors Vsevelod Meyerhold, Nikolai Evreinov, and Konstantin Stanislavsky and in the process were able to envision a different way of looking at the world.

A 1949 US production of Hamlet was a fledgling effort at cultural diplomacy. It was the first show to tour abroad with official support from the US government. In addition, the production itself was the work of the first state-supported theatre in the US, the Barter Theatre. Hamlet performed at the Elsinore festival in Denmark and then traveled to military bases in occupied Germany. Its true audience, however, was not the European spectators who mostly flocked to the show out of curiosity, but US citizens at home who need to be convinced about the powerful potential of international artistic exchange.

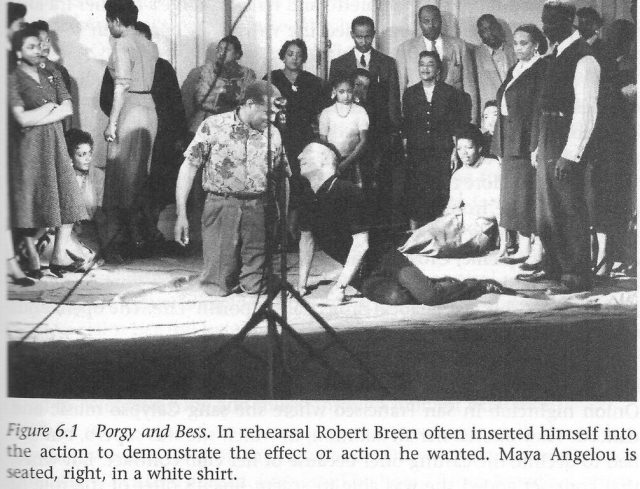

The team behind Hamlet went on to produce the 1952-56 world tour of George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess. The revival performed in Western and Eastern Europe, Latin America, Africa, and even Russia, the first US production to do so. Everywhere the company went it was hailed as a triumph. The artists involved were invested in demonstrating that the arts’ were worthy of ongoing public support, and that they had something essential and unique to add to public discourse. The US government leveraged the production for their own purposes. The government investment in cultural diplomacy was two-fold. First it was an attempt to communicate (as with Hamlet) that the US had vibrant and sophisticated culture that could be positively compared with any in the world. If the Soviets were going to use ballet and symphonic orchestras to prove their complexity and worldliness, the US would counter with jazz, dance, and theatre.

The second was race. During the Cold War the US argued that the nation stood for freedom, and that democracy guaranteed equal rights and opportunities for all. But that presented the US with an extraordinary challenge. White supremacy and democracy had historically been coeval, and US national identity had been produced by this relationship. Now the US wanted to argue for democracy as a resistance to intolerance, particularly racism and colonialism. To do so would require evidence that racism was not an integral part of the nation, and that the experiences of people of color were far better than they were usually depicted. Cultural diplomacy provided a way to make that argument without seeming to—every musician, performer, and speaker was positioned as a refutation of the charge that the US was a racist apartheid state. None of these three productions documents the new and influential plays being written in the US, or, with a few exceptions, the theatre artists whose names would become ubiquitous in US theatre history. Instead these productions moved theatre’s cause along, and supported the argument that theatre was necessary and essential.

Theatre internationalists around the world believed that live performance could inspire and ensure a better, a more peaceful, world. They took each other’s work seriously and created new work for their own audiences based on what they had learned from each other even when they were not in agreement about what constituted an improved world. They built a series of interdependent institutions to further theatre’s influence, to give it greater visibility and prominence, and, most importantly, to ensure its survival. Theatre could be imported and exported and exchanged so it could provide a point of contact among nations. Internationalism, as it was embraced by utopian theatre practitioners in the twentieth century, ceaselessly negotiated the demands of the state with those of the people whose stories needed to be told to each other.

For more great books on modern theater, look here.