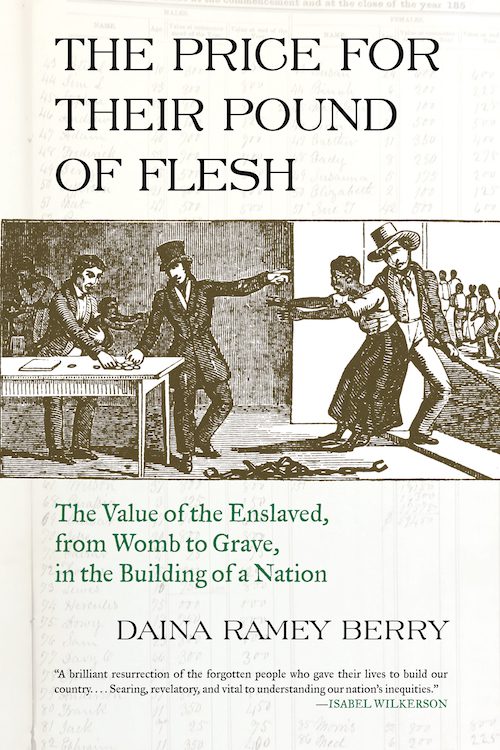

The Price for their Pound of Flesh is the first book to explore the economic value of enslaved men, women, and children in the American domestic slave trade, from before they were born until after their death, in both public and private market transactions and appraisals. How was a slave’s price determined? How did planters and traders establish values for enslaved people with specific ages, specific skills, or specific health conditions? Studies of the domestic slave trade rarely discuss the economic meaning and social significance of the market values and appraisals assigned to enslaved people. When they do discuss slave prices, the focus has mostly been on prime male slaves. This study examines slave prices of women, men, and children during their entire “lifecycle,” including preconception, infancy, childhood, adolescence, adulthood, the senior years, and postmortem.

Another original component of this work is its illumination of enslaved people’s reaction to being appraised, bartered, and sold. Enslaved people remembered their values. “Men or mechanics were worth from 12 to 1300 dollars,” recalled one former slave, “and boys 8 and 9 years old, 5 and 6 hundred dollars.” The book explores slaves as commodities and as people through all phases of their lives. Did slaves know their market values and/or appraisals? Were they impacted if they commanded high prices or if their buyers considered them “bargains”? How did their monetary values shape relationships within the enslaved community and beyond? Rather than explore how traders turned “people into prices,” as historian Walter Johnson did in Soul by Soul, this book converts the prices into people. The dollar values placed on enslaved people have more meaning when one considers their humanity, how they may have felt on the auction block, and how they responded to being sold “to the highest bidder.”

Now that the book is complete and on sale, I would like to share a few other thoughts about this decade long endeavor. First, I love being in the archives and have been called an “archive rat” with pride. The experience of discovery feeds my desire to locate untold stories and share them with readers. Enslaved people drove this research just as plantation records offered foundational evidence and a starting point. I combed through thousands of records to find individual enslaved people who were often overlooked in history. I wanted to bring their buried stories to life and to highlight their thoughts. The research was difficult and many of their accounts are heartbreaking, but when I consider that people survived and lived to tell their stories I was encouraged. The voices of the enslaved motived me to write and to keep writing. Sadly, for some I only knew a name and no other details. Others offered much more fruit for me to share—testimonies, emotions, feelings, opinions, etc. This book is meant to give a voice to enslaved people, particularly about their experiences of, and responses to, the commodification of their bodies.

Dr Berry and UT graduate student Lauren Henley offer these suggestions for further reading on the economies and medical histories of enslaved people in the United States.

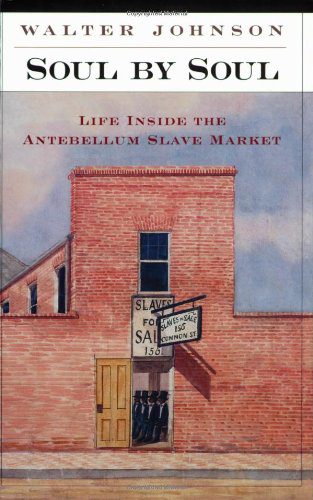

Walter Johnson, Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market (1999)

In Soul by Soul, Walter Johnson imagines the moment of a slave sale from the perspective of the buyer, the seller, and the enslaved individual. Drawing from slave narratives, enslavers’ letters, docket records, and nineteenth-century economic descriptions of the enslaved, Johnson highlights the processes by which labor, humanness, capital, race, and power were negotiated in physical and metaphorical spaces throughout the American South, showcasing the brazenly economic and political motivations that built the institution one sale at time.

Michael Sappol, A Traffic of Dead Bodies: Anatomy and Embodied Social Identity in Nineteenth-Century America (2002)

Exploring the academic and popular histories of anatomy in American society, Michael Sappol considers the role corpses played in shaping American identity and subjectivity. His examination of nineteenth-century medical education and professionalization reveals a network of professors, students, grave robbers, state officials, and law enforcement officers directly benefiting from the death of others. The corpses that were often literally dragged into this operation were those of the poor and dispossessed, overwhelmingly represented by black men and women, in slavery as well as in freedom. Cadavers provided hands-on training for medical students, but they also reinforced notions of identity, class, culture, and hierarchy for all parties involved in their trafficking.

Calvin Schermerhorn, The Business of Slavery and the Rise of American Capitalism, 1815-1860 (2015)

The Business of Slavery examines the buying, selling, and moving human of chattel in the nineteenth-century interstate slave trade, focusing on the forced movement of enslaved men, women, and children from the mid-Atlantic region to the Deep South.

Harriet Washington, Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present (2006)

Medical Apartheid charges the American medical profession with conducting extensive involuntary research on black bodies since at least the eighteenth century. From abusive and painful gynecological experiments on enslaved women to the now-infamous Tuskegee syphilis trials, Washington inverts the dominant narrative by showing that medical histories have always been written from the perspective of the field’s professionals, which has hidden the fact that advances of American medicine have been literally inscribed onto the bodies of society’s least fortunate—blacks, the poor, women, the infirm, and children. For centuries blacks’ mistrust of medical institutions has not been the manifestation of irrational fear, but a response to the failure of medical professionals to do no harm.

Craig Wilder, Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities (2013)

Directly linking elite universities in New England to Southern slavery and the eradication of Native Americans, Ebony and Ivy highlights both the all-encompassing influence of slavery on American society as well as the extent to which elite universities informed popular perceptions of race, slavery, and Americanness. This entangled history of education, slavery, exploitation, and capitalism challenges longstanding notions of ivory tower benevolence.