by Jesse Ritner

On February 1, 1894, Frank Cook stumbled down from the Elk Mountain range, passed through the frozen town of Ashcroft, and trudging through the deep Colorado snow arrived in Aspen, Colorado. His mining partner, Mr. Spake, was dead.

Mining accidents were common in late nineteenth-century Colorado. Mr. Cook, likely weary and cold from his arduous trip, reported that he “entered the tunnel and found his partner with his head blown off and his body terribly mangled. A steel priming rod had passed clear through the body.”[1] Memory of his partner’s death may have intensified as Cook descended from the frigid elevations. Or the reporter of the Aspen Daily Times might have allowed his imagination to run wild. Unfortunately, the truth of the incident was not forthcoming. February in the Roaring Fork Valley is snowy. The citizens of Aspen waited anxiously for further information to arrive.

I, on the other hand, benefited from immediate access to Colorado Historical Newspapers. Spake was not killed by dynamite.

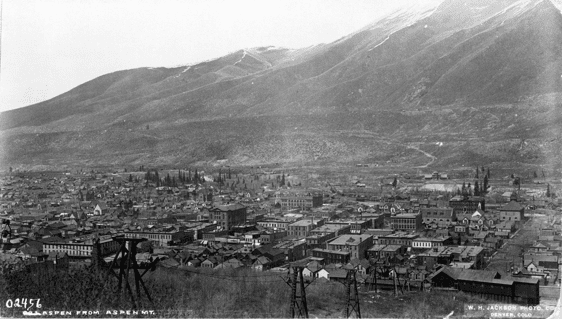

Frank Cook likely arrived in the back range of the Rocky Mountains by 1889. However, due to his exceedingly common name (as the archivist in Aspen commented he may as well be named John Smith), he is difficult to trace. Nevertheless, he periodically reappears in the Aspen papers. Notably, despite his Anglophone name, Frank Cook was known as a Frenchman.[2] (Or at least as French Canadian.) As such, he was a notable presence in the bustling and growing town populated by approximately 8,000 people.

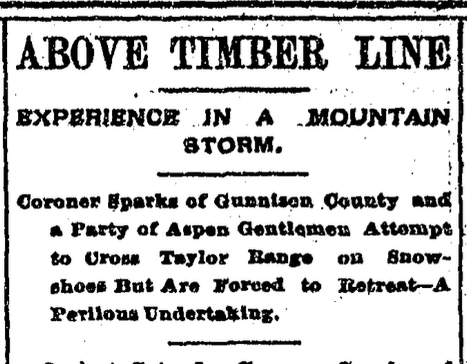

The Times reported on February 21 that Cook was still lingering about in Aspen. The authorities, having sent word to Gunnison that a coroner was needed, waited almost three weeks for Mr. Spark to arrive. (Even today, a February trip from Gunnison to Aspen is often treacherous.) On February 18, shortly after the coroner’s arrival, Cook, Sparks and a few others “formed a team to go over the range to the Big Four properties, having in view an official investigation of [Spake’s] death.” The team never made it.

The Aspen Daily Times article is gripping. The accent to the Elk Range was “extremely arduous.” The roads had “drifted full” forcing the party to “shovel snow a great part of the distance.” At Ashcroft the spirited men decided to “brave the dangers of the Taylor range on Norwegian snowshoes.” Despite the grind of their trip to Ashcroft, disaster did not strike until they reached the top of the range. There, at 12,000 feet, they encountered a dangerous storm. The papers reported that “the wind whistled and shrieked about the ragged peaks; it howled and groaned as it piled up snow… in the solitude and loneliness of these bleak and cheerless crags, the situation was enough to strike terror to the bravest of hearts.” The party, facing almost certain “destruction” if they continued turned around and skied back to Ashcroft.[3] A team from Gunnison, frustrated by the failures of Aspen, took up the search. It was only then that The Times reported, “Cook’s story of the death of Spake [was] not borne out by the surroundings in the tunnel.” A warrant was released for his arrest. But, Mr. Cook had already fled town.

The papers were mystified that Cook made “no attempt to conceal himself.” He had “deported himself generally as one entirely unconscious that suspicion of complicity in the affair could rest upon him.”[4] He not only took part in early attempts to recover the body, but he even let Mr. Bowman, owner and amateur curator of the Bowman Saloon and Musee, take his picture before he left town. In the end, he was found on the streets of Denver, where two sheriffs arrested him, and shipped him by train to Gunnison to stand trial.[5]

The story above is a perfect western. A dark man of dubious identity, out in the wilderness, far removed from civilization commits the ultimate crime. White men in cowboy hats ride horses, mountaineer, and ski to solve the case. They test their strength. Conquer nature. And in the end – after death, danger, and a dramatized standoff in the streets of Denver – the criminal is captured and faces justice. The dramatized story of manifest destiny is pushed to its limit, testing the resilience of American character against the chaos and violence of the still nebulous West, and in the end the violence redeems itself through the court system. I won’t lie. The thrill of the western drew me in. And there is perhaps no genre as titillating as frontier newspapers recounting in detail the crimes of their days. However, this story also reveals the limits of cinematic depictions of the American west.

Cook was born in upstate New York, on the St. Regis Indian Reservation. His mother was an Irish immigrant to Canada. His father was a “near full-blood St. Regis Indian.” Back home he was known as Frank Boots – his father adopted the last name due to the “fine boots with red tops” that he often wore, and which stood in opposition to the moccasins most Mohawks preferred.[6]

Historians, artists, and politicians have long discussed the tragedy of the “vanishing Indian.” Convinced that Indians continued to exist exclusively on reservations, if at all, Indigenous people have been written out of both the historical and cultural memory of our country. Only recently have historians – Phillip Deloria (Standing Rock Sioux) and Jean O’Brein (White Earth Anishinaabe) are but two examples – begun challenging this myth. Cook is further proof of the ways Indians have been written out of history. Not only is he from New York, a state whose Indian history supposedly finished before the Civil War, but he counteracts narratives that whitewash western expansion. The Indian Wars were over by this time, but the simple reality of Cook’s presence demonstrates that Natives still inhabited the mine filled mountainous landscapes of the Rocky Mountains.

His story demonstrates the finicky nature of identity. His father was “near full-blood,” his mother was Irish, and Frank, as a result, would have been “half-blooded.” This qualitative measuring of Indianness by local newspapers suggests the importance of biological and hereditary constructions of race during the time period. Yet, Cook’s own narrative, presenting himself as a Frenchman, shows how even in legally racialized societies, mobility could loosen the holds of identity on individuals, but Cook’s decision to pass as French does not take away his Indigenous heritage.

For many, Frank Cook’s story may not be an obvious Indian story. He lived off a reservation. He spoke English and French. And by the language of the day he was “half-blooded.” But too often we fall victim to nineteenth-century theories that argue when such people fail to fit within our pigeonholes, they were inauthentic. It is precisely this thought process that erases Indigenous people from our histories. Cook’s story shows that Indians continued to be part of the history of the Rocky Mountains.

[1] 2/1/1894

[2] 4/7/1894

[3] 2/21/1894

[4] 3/3/1894

[5] 3/9/1894

[6] 4/7/1894

Also by Jesse Ritner on Not Even Past:

The Curious History of Lincoln’s Birth Cabin

Paying for Peace: Reflections on “Lasting Peace” Monument

What Makes a Good History Blog?

You may also like:

US Survey Course: The American West, Native Americans, and Environmental History

The Tiger by Nathan Stone

Dorothy Parker loved the Funnies by David Ochsner