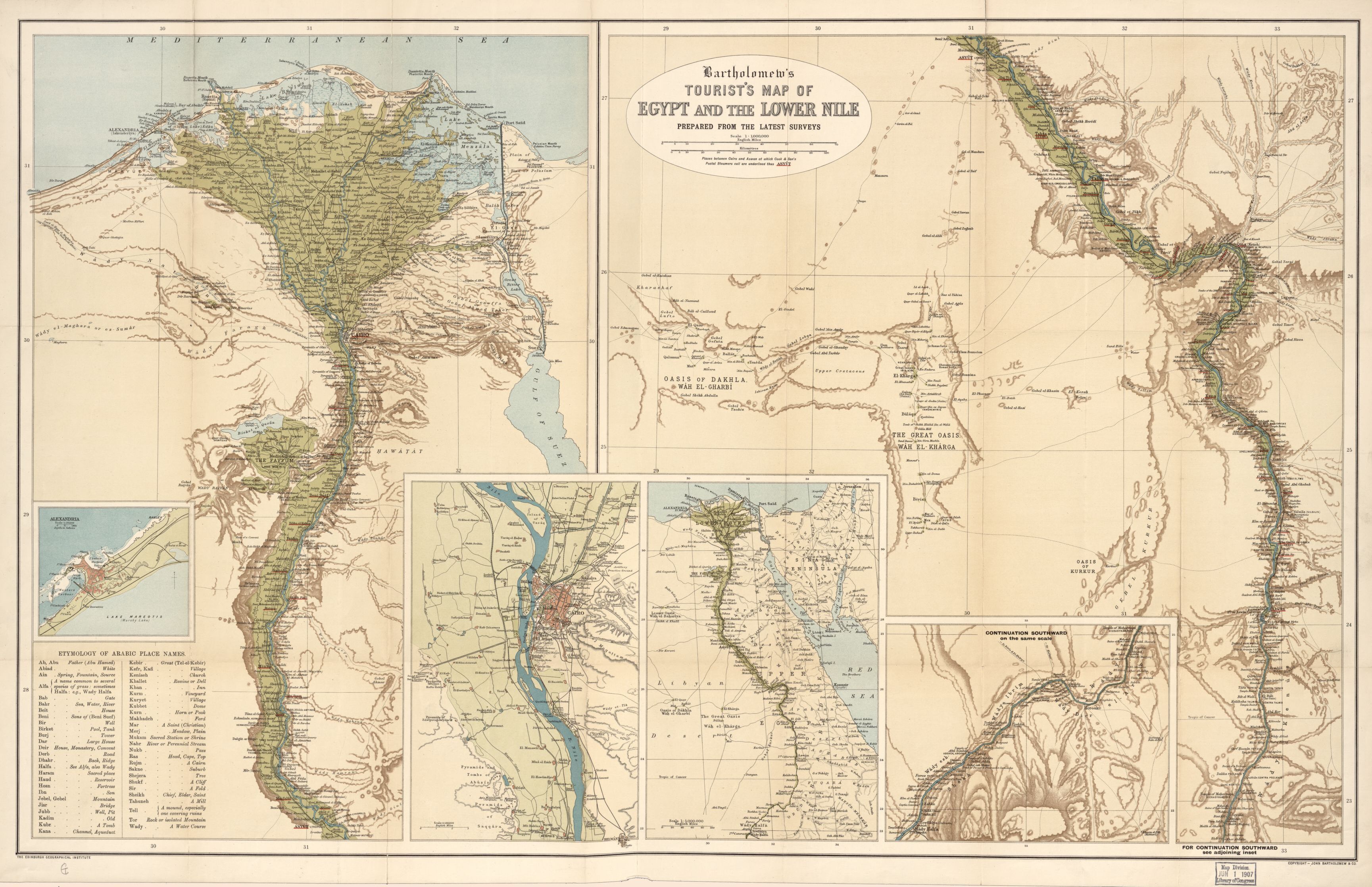

Jennifer Derr takes her readers down the Egyptian Nile River, past its newly constructed dams and flowing into its irrigation canals, providing them with the opportunity to dive into the complexity of British colonialism in Egypt in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Following their invasion of Egypt in 1882, the British began a huge infrastructural project aimed at harnessing the natural power of the river to the material needs of the empire. Cotton was the name of the game. Millions of Egyptians were forcibly enlisted to build dams and dig irrigation canals that contributed to increased cotton production and ensured a constant supply of cheap raw materials for the mills in Britain. Derr’s analysis binds together politics, economy, and environment to show what colonialism looks like on the ground and how British control practices shaped, fostered, and maintained the colonized land and society.

Derr argues that in the Egyptian experience, the colonization of men and nature were interchangeable processes. The new irrigation infrastructures irreversibly transformed the Egyptian landscape, overflowing some areas and drying others. Ultimately, changes in nature penetrated the bodies of Egyptian subjects who suffered from diseases directly linked both to their long days of working in muddy canals and to dietary changes – mainly the transformation from a wheat-based to a corn-based diet – imposed by the changes in land usage. In pointing to the connection between nature and the human body, Derr demonstrates the complexity of the colonial economy and its influence over meta-economic processes and individual experiences of subjectivity, citizenship, class, economic abilities, and even personal health.

One notable achievement of The Lived Nile is its contribution to a growing attempt to break down the timeline of the Egyptian colonial experience. Although Egypt officially gained independence in 1922, foreign (often British) intervention in the country’s internal affairs remained a permanent issue until 1956 when, following the Suez crisis, the last British soldier finally left Egyptian soil. Derr cleverly demonstrates that colonial control materializes in more than merely a physical presence, as she dives into the complexity of colonial intervention in daily life in its various forms and implications. At the end of the nineteenth century, for example, it was the British irrigation engineers who practiced foreign control and authority over irrigation projects. By the mid-1930s, it was the turn of other experts – this time medical expeditions sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation to promote invasive medical treatments in the countryside, who practiced foreign control over the bodies of the Egyptians. Here again, as in the case of changes in nature, Derr demonstrates the nuanced and complex forms of the colonial experience.

Rather than a strictly environmental history of colonial Egypt, Derr presents a bio-political reading of the relationships among groups of people and between humanity and nature. Using her previous training as a biologist, Derr identifies the various ways in which the agency of non-human actors influenced human lives in Egypt. These range from great natural phenomena like the Nile to the microscopic organisms (Schistosoma) that multiplied following the expansion of irrigation canals, attacking the peasants’ (Fellahin) digestive system. However, for Derr, none of nature’s many representations – the Nile, corn, swamps, and intestinal worms — bear importance on their own; they all become relevant to the story only when they serve a purpose in the political struggles over resources and control.

While presenting a well-crafted re-conceptualization of Egypt’s bio-colonial experience, Derr often neglects the voices of the local population. In fact, the readers meet the Egyptians only when they interact with colonial officials and mostly through the eyes of the latter. Critical as Derr’s attitude might be towards these encounters, the reader cannot escape noticing the clear power relations between the two groups and the British sense of superiority that accompanies every interaction. One notable example is the way British irrigation engineers disregarded the proficiency of their Egyptian counterparts during their shared work to reshape the Nile’s dam system at the end of the nineteenth century. The influence of Egyptians over the landscape is also missing in the discussion about health initiatives taken by the Rockefeller Foundation during the 1930s. We now know that during these years the Egyptian government was involved more than ever in social projects in rural areas, but Derr seems to dismiss the Egyptian contribution in favor of her bio-colonial argument. Paying more attention to local voices might have contributed to an even deeper analysis of Egypt’s bio-colonial experience.

Though at first glance, The Lived Nile seems to be relevant only for environmental or social historians of modern Egypt, the incorporation of multiple agencies, methodologies, and ideas makes it relevant to a wide range of audiences. Derr’s documentation of what it means to be colonized sets a strong conceptual frame most likely to be picked up by scholars outside of the Middle East in the years to come. On top of all her academic achievements, Derr wisely avoids complicated phrases and jargon, except when the Latin term is necessary (good luck saying Schistosoma mansoni without breaking a tooth). Her straightforward language and complex-yet-accessible ideas make the book readable and enjoyable for curious academic and non-academic readers alike.

You might also like:

The Curious Case of the Thomas Cook Hospital in Luxor

Paris, Capital of Modernity by David Harvey (2006)

Anxieties, Fear, and Panic in Colonial Settings: Empires on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown edited by Harald Fischer-Tiné (2016)