Note: This article was originally published in Perspectives on History. You can see the original article here.

When asked near the end of the chaotic spring 2020 semester how my sudden shift to online teaching went, I responded, “It was twice the work and half the fun of teaching in person.” Once the semester was over, however, I received messages from students thanking me for carrying on close to normal and providing them with stability in a very stressful time. Some even proclaimed it their best learning experience ever. Perhaps students at the University of Texas at Austin are just forgiving and understanding of a professor who, after four decades of teaching nothing but in-person classes, was suddenly forced last March to adapt to teaching online. Still, perhaps both my summary judgment and the students’ were correct. Despite the difficulties and frustrations, my efforts to clearly illustrate the central message of the course and make the transition to online as seamless as possible may have paid off.

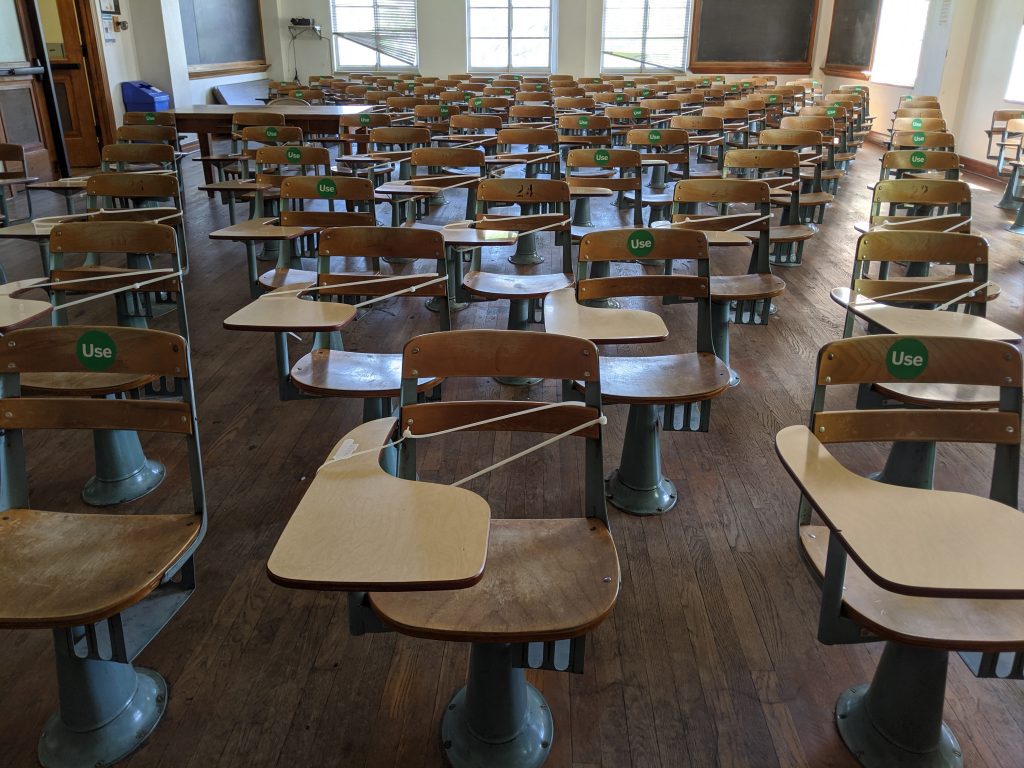

Online teaching is indeed twice the work, especially for a first-timer. I quickly upgraded my technology at home while UT scrambled to provide the best platform for teaching remotely. Everything was new—new equipment at home, new systems to master, new difficulties in maintaining a classroom community and communicating with each student. Because I had students scattered around the world, I taught each class asynchronously. That forced me to imagine a full classroom while switching back and forth from focusing the camera on me to screen sharing quotations, photographs, music, or the lecture outline for the day. Thankfully, over half of the 40-person class attended synchronously, but looking at their faces on my screen, keeping an eye on the chat feature, responding to raised hands, and trying to maintain the normal flow added another level of difficulty. The whole experience felt like juggling while balancing on a beach ball. I never ended a class thinking that I had nailed it that day and that things went especially well.

Stress and worry made the teaching experience half the fun, but I also missed the human contact with students. It was impossible to read the body language of students for clues on how the class was going and to look them in the eyes when responding to questions. I also missed the adrenaline rush after class, when students come up and declare “you made me think about this” or “that was a new idea for me.” Instead of inspiring students to think about the past and the evidence that supported new ways of viewing the past, it seemed that far too often I was simply performing and pushing information down the throats of students. Class seemed flat with fewer probing questions asked than during a normal in-person class.

Given the challenges and off-putting nature of online teaching, why were students generally positive about the experience? Crucially, we had almost half a semester together in person. They knew me, and I knew them. We had built community, and they were comfortable asking questions. I had established a certain rhythm in each class, and I decided to follow that rhythm online to the extent possible—which turned out to be a wise decision. In my undergraduate course on the history of Texas, I would open the class with a recording of a song from a Texas artist or a song that especially fit the topic of the day. For example, when the topic was lynching and white supremacy, I opened with Billie Holiday singing “Strange Fruit.” With the camera on me, I spoke about the major argument for the day and the song. Then I shared a photo of the 1916 lynching of Jesse Washington in Waco, Texas, while I continued speaking. Then back to the outline of points to be covered for the day, and so on, until near the end when I shared a quote from a newspaper that illustrated the commonplace nature of lynching. That led to a concluding discussion of the questions and thoughts to be carried forward from that day. The experience was not identical to our face-to-face sessions, of course, and I had to pay special attention to fielding questions and comments from students as they came up. Yet the pattern was familiar enough to the students to allow them to continue to get something out of the course.

I also doubled down on emphasizing the central organizing premise of the course—the Texas you thought you knew, the Texas you imagined, was probably not the real Texas of the past. I made a special point of focusing on that theme at the conclusion of each class, instead of letting it percolate naturally as I do in person. In other words, I simplified my approach and made it more direct as I encouraged them to think about the past. I tried to demonstrate how historians work and to make students historians in training.

I should also admit that because of other duties I was only teaching one course. Teaching that one course was exhausting, and I am not sure I could have maintained the focus and energy needed to effectively teach online in multiple classes.

While I had hoped to never repeat the online teaching experience, the COVID-19 pandemic has worsened in Austin and across Texas since last spring. This fall, I am teaching one graduate class online, and I have reflected on what I learned from the spring. A graduate seminar is a different animal from an undergraduate class, but some lessons carry over.

- Take the time in advance to familiarize yourself with the equipment and the platform you will use.

- Pay special attention to building a community of inquiring scholars. I will not have the advantage of two months of face-to-face time, but I plan to use such things as the discussion features in Canvas and Zoom breakout rooms. About two-thirds of the way through each session, I will divide the class into two breakout rooms, so students have a greater opportunity to share ideas in a small group. I will visit each group to answer questions and spur debate. Then when we reconvene as a whole, a different student each week will report back from the breakout rooms. By using such techniques, I hope to make the seminar a shared experience instead of an experience that leaves each student feeling isolated.

- Keep as much the same as possible—but realize that a three-hour Zoom seminar will be exhausting for everyone. We will need two breaks instead of one, and the change of pace provided by the breakout rooms should also help lessen fatigue.

- Keep it simple, and keep the central message front and center.

Off I go into what I still hope is my last time teaching online. The experience may remain twice the work and half the fun, but at least I have a plan and evidence of modest past success. Stay optimistic and energetic. Our students need that.

Walter L. Buenger is Summerlee Foundation Chair in Texas History and Barbara Stuart Centennial Professor in Texas History at the University of Texas at Austin.

This article originally appeared as Remote Reflections: Twice the Work and Half the Fun in Perspectives on History in September 2020.

Images of Garrison Hall courtesy of Grace Goodman.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.