by May Helena Plumb

In honor of the centennial of the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, the 2022 Lozano Long Conference focuses on archives with Latin American perspectives in order to better visualize the ethical and political implications of archival practices globally. The conference was held in February 2022 and the videos of all the presentation will be available soon. Thinking archivally in a time of COVID-19 has also given us an unexpected opportunity to re-imagine the international academic conference. This Not Even Past publication joins those by other graduate students at the University of Texas at Austin. The series as a whole is designed to engage with the work of individual speakers as well as to present valuable resources that will supplement the conference’s recorded presentations. This new conference model, which will make online resources freely and permanently available, seeks to reach audiences beyond conference attendees in the hopes of decolonizing and democratizing access to the production of knowledge. The conference recordings and connected articles can be found here.

En el marco del homenaje al centenario de la Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, la Conferencia Lozano Long 2022 propició un espacio de reflexión sobre archivos latinoamericanos desde un pensamiento latinoamericano con el propósito de entender y conocer las contribuciones de la región a las prácticas archivísticas globales, así como las responsabilidades éticas y políticas que esto implica. Pensar en términos de archivística en tiempos de COVID-19 también nos brindó la imprevista oportunidad de re-imaginar la forma en la que se llevan a cabo conferencias académicas internacionales. Como parte de esta propuesta, esta publicación de Not Even Past se junta a las otras de la serie escritas por estudiantes de posgrado en la Universidad de Texas en Austin. En ellas los estudiantes resaltan el trabajo de las y los panelistas invitados a la conferencia con el objetivo de socializar el material y así descolonizar y democratizar el acceso a la producción de conocimiento. La conferencia tuvo lugar en febrero de 2022 pero todas las presentaciones, así como las grabaciones de los paneles están archivados en YouTube de forma permanente y pronto estarán disponibles las traducciones al inglés y español respectivamente. Las grabaciones de la conferencia y los artículos relacionados se pueden encontrar aquí.

A key thread running through Dr. Brook Danielle Lillehaugen’s career is access—to language, to history, and to education. She recognizes that linguistic research on Indigenous languages is insufficient if members of Indigenous communities cannot access it. Therefore, throughout her career she has sought to remove barriers to such access via creative, collaborative research that goes beyond traditional academic practice.

I have been fortunate to know Lillehaugen since 2012, when she taught my very first linguistics class at Haverford College. As a former student and a current co-author, it’s a pleasure to reflect on Lillehaugen’s research in this review. My own academic path has been shaped by her leading example of collaborative research that reaches “beyond the academy.” I believe linguistics as a field and the broader academic world has much to learn from Lillehaugen’s style of scholarship.

At the center of Lillehaugen’s research are the Zapotec languages and the people who speak them. Zapotec is a family of languages indigenous to Oaxaca, Mexico. Today over 400,000 Zapotec people live in Oaxaca and in diaspora communities throughout Mexico and the United States. As Indigenous survivors of a colonialist and nationalist history (and present), Zapotec people face systematic marginalization. Anti-Indigenous sentiment, especially as manifested in discriminatory language policies—such as those banning children from speaking Indigenous languages in Mexican schools in the latter half of the 20th century—has caused many Zapotec families to shift to Spanish as an act of self-preservation.

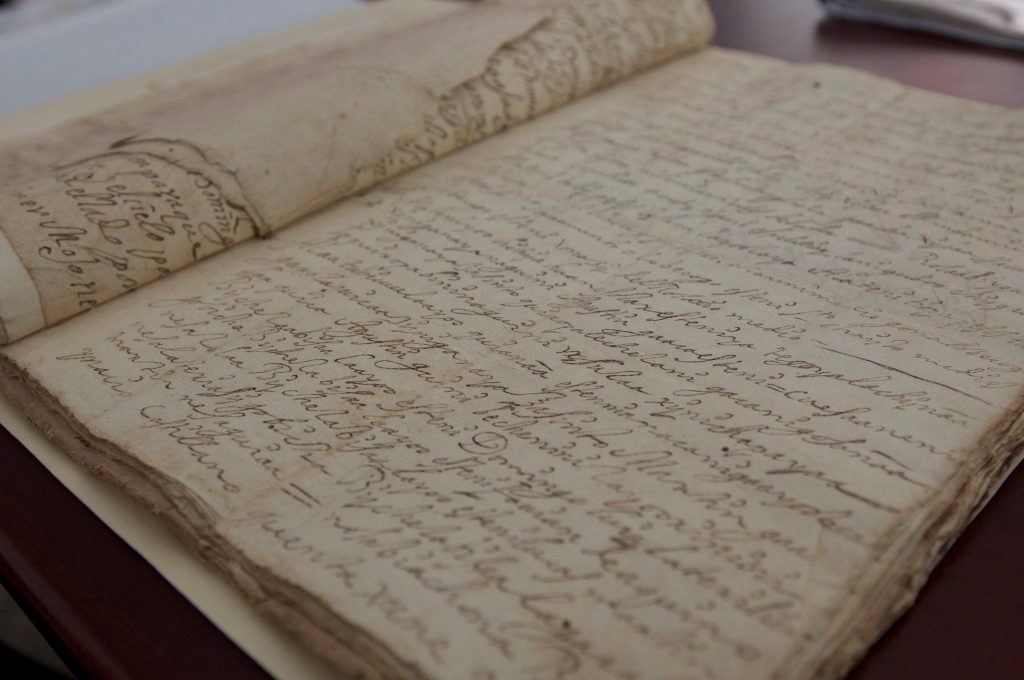

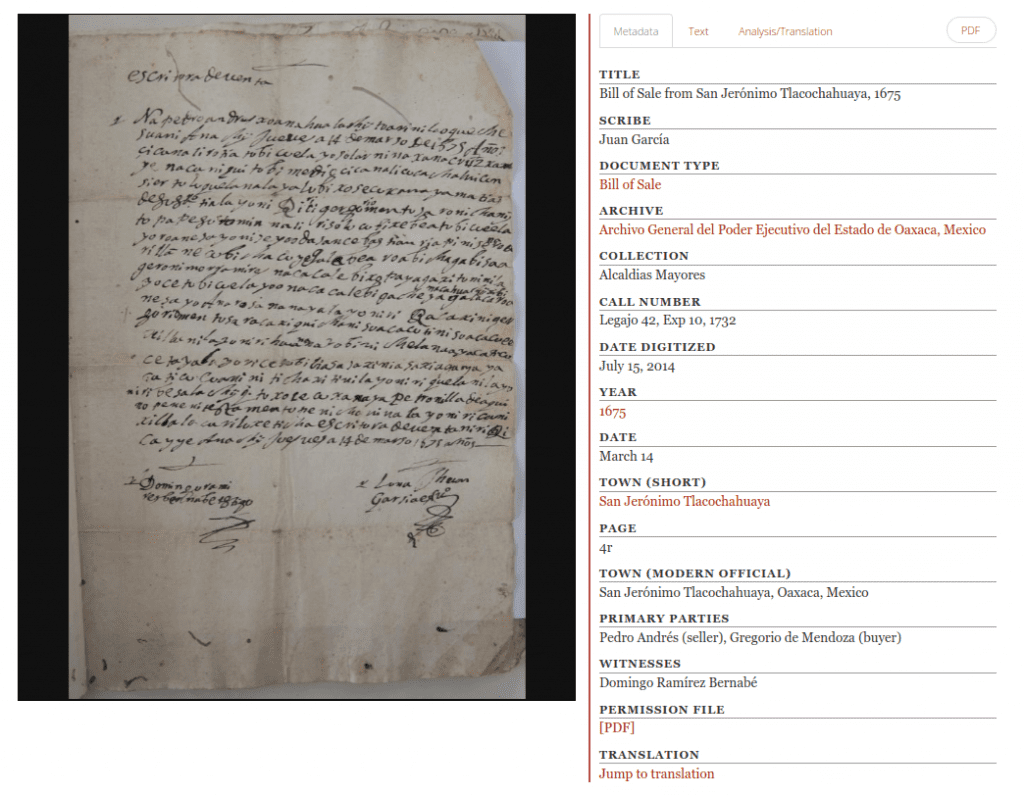

Regardless, many Zapotec people have and continue to actively resist this language shift. One useful tool for Zapotec scholars and activists has been the corpus of colonial-era documents written in Zapotec languages, which includes legal manuscripts as well as religious and descriptive linguistic texts. However, Zapotec people face numerous barriers in accessing these documents: the Zapotec language written during the colonial period is significantly different from those languages spoken today; the archives housing these documents are scattered throughout Mexico, the United States, and even Europe; and furthermore, many archives actively discriminate against Indigenous knowledge-seekers.

Lillehaugen’s research program combines linguistic analysis of the grammar of Zapotec languages with tools from digital humanities to promote access to the Colonial Zapotec corpus, allowing stakeholders to engage more deeply with the history of Zapotec knowledge, culture, politics, and language. Her scholarship is expansive and radically collaborative—her co-authors include Zapotec scholars and activists, undergraduate students, historians, and librarians. Her publications range from traditional academic articles in the International Journal of American Linguistics and Language Documentation and Conservation, to pedagogical materials, digital dictionaries, and documentary films. Lillehaugen received her Ph.D. in linguistics from the University of California, Los Angeles, and she is currently an associate professor in the Tri-College Department of Linguistics at Haverford College.

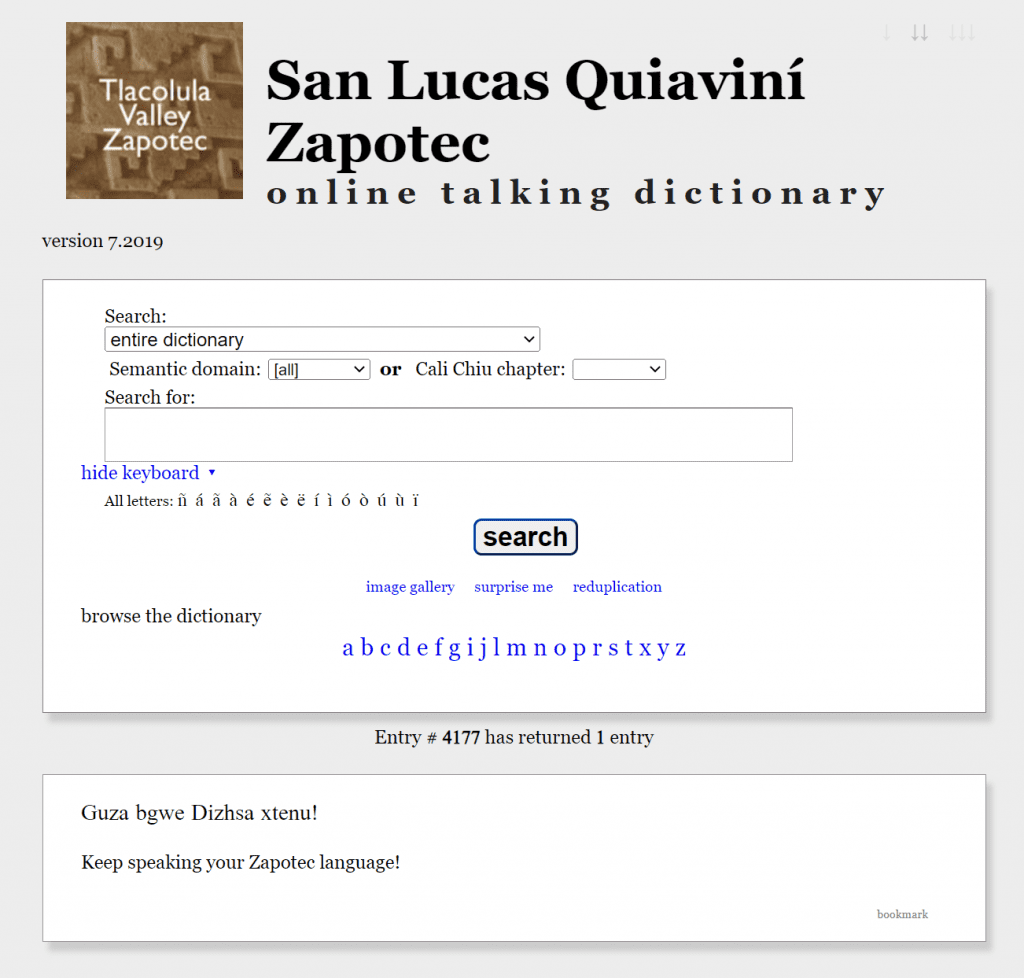

Lillehaugen’s primary project—and the topic of her talk at the 2022 Lozano Long Conference—is Ticha, a digital explorer for Colonial Zapotec (ticha.haverford.edu). The core goal of the Ticha Project is to make Colonial Zapotec texts accessible to a diverse public, and in particular to Zapotec people. Lillehaugen leads a large team of linguists, activists, historians, students, and librarians, including Zapotec and non-Zapotec collaborators, to create resources that can support both community-based Zapotec initiatives and interdisciplinary scholarly research. Digital humanities has been a key component of realizing this goal: the Ticha website curates high-quality images of these texts with transcriptions, translations, and historical context. The website also features a Colonial Zapotec vocabulary list,[1] which is integrated with audio recordings from living Zapotec speakers. This draws on another one of Lillehaugen’s projects: the Zapotec Talking Dictionaries.[2] In order to address specific goals and needs of Zapotec community members, Lillehaugen and the rest of the Ticha team have also created pedagogical materials about Colonial Zapotec, run workshops for Zapotec people to learn about colonial Zapotec writing and history, and brought Zapotec people into archives[3]—a radical act, given the historical and present-day exclusion of Indigenous people from these spaces.

Most recently, Lillehaugen led a 2019 ACLS Digital Extensions grant with Zapotec scholars Felipe H. Lopez (Seton Hall University) and Xóchitl Flores-Marcial (California State University, Northridge) and librarian Mike Zarafonetis (Haverford College Libaries) to expand the resources available on the Ticha site and write pedagogical materials helping new users explore and understand Colonial Zapotec texts. The result is Caseidyneën Saën — Learning Together,[4] a digital volume of teaching modules on topics ranging from the Colonial Zapotec number system to how Zapotec people have used Colonial Zapotec texts to learn more about the languages they speak today. There is also a corresponding volume in Spanish, Aprendemos Juntos.[5] The lessons are appropriate for self-study or for use in high school and college classrooms.

The volume is directed toward a broad audience and assumes no experience in linguistics or Mesoamerican history, but the editors centered a Zapotec audience as primary. Ticha focuses on colonial-era materials, but Lillehaugen and her colleagues explicitly connect this research to Zapotec languages spoken today, actively combating false, harmful narratives that relegate Indigenous languages and cultures to the distant past. For example, the teaching modules in Caseidyneën Saën feature videos of Zapotec people, compare Colonial Zapotec grammar with that of languages spoken today, and explicitly encourage Zapotec readers to explore these topics in their own languages and communities.

Throughout her career Lillehaugen has also prioritized support for educational spaces where Zapotec people can engage with their languages and history. In earlier projects, she has helped create social media networks that support Zapotec people writing their languages[6] and has run workshops in Oaxaca on reading Colonial Zapotec documents. As part of the development of Caseidyneën Saën, Lillehaugen, Lopez, and Flores-Marcial designed virtual workshops for Zapotec people to learn about Colonial Zapotec using these teaching modules.[7] Participants in the workshops, who came both from Oaxaca and from Zapotec diaspora communities in the United States, formed a new transnational community of Zapotec activists who can support each other’s work moving forward. Lillehaugen and her collaborators also provided a framework and financial support for participants to run their own workshops in their communities, building the foundations for continued education in the future.

As I pursue my own graduate research on Zapotec languages, I’m lucky to count Brook as a teacher, a mentor, a colleague, and a dear friend. My collaboration on Ticha and Caseidyneën Saën has deeply shaped how I view my research and my progress through academia. In writing Caseidyneën Saën and pursuing other Ticha initiatives, Brook models a radically collaborative method of work, one which prioritizes Zapotec perspectives and brings together scholars from a variety of institutions, disciplines, and stages of their career to create projects that are deeply rooted in community, reciprocity, and resistance.

May Helena Plumb is a Ph.D. candidate in Linguistics at the University of Texas at Austin. Her graduate research investigates the expression of temporal-modal semantics in the Zapotec languages of Oaxaca, Mexico, with a particular focus on Tlacochahuaya Zapotec. Her broader interests extend to digital humanities, the preservation of language data, and supporting intellectual infrastructure for Indigenous people doing language work. She is a co-author on the Ticha Project, a digital text explorer for Colonial Zapotec documents (ticha.haverford.edu), and a co-editor of Caseidyneën Saën – Learning Together, a collection of pedagogical materials on Colonial Valley Zapotec.

[1] https://ticha.haverford.edu/en/vocabulary/A/

[2] In collaboration with the Enduring Voices Project; http://talkingdictionary.swarthmore.edu/zapotecs/

[3] https://twitter.com/xochizin/status/1449064042593726469

[4] http://ds-wordpress.haverford.edu/ticha-resources/modules/

[5] http://ds-wordpress.haverford.edu/ticha-resources/recursos-de-ticha/

[6] See Lillehaugen, Brook Danielle, 2016. Why write in a language that (almost) no one can read? Twitter and the development of written literature. Language Documentation and Conservation 10: 356-392. Online: http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24702

[7] See Lillehaugen, Brook Danielle, Xóchitl Flores-Marcial, May Helena Plumb, George Aaron Broadwell & Felipe H. Lopez, 2021 Recovering Words, Reclaiming Knowledge, and Building Community: Ticha Conversatorios. Paper presented at the LASA2021 Virtual Congress: Crisis global, desigualdades y centralidad de la vida. Online: https://youtu.be/ k5QZkyjsvHQ